Yuri Drozdov, Soviet spymaster who worked in Mao’s China then planted agents across the West, dies at 91

They were known as the illegals, men and women who adopted the identities of the dead, worked as priests, poets, actors and inventors, and quietly gathered intelligence for the Soviet Union during the long years of the Cold War.

Based in nondescript American suburbs and bustling European capitals, they spent up to two decades under deep cover developing the trust of their neighbours and employers while stealing secret information about nuclear weapons, missile systems, Western intelligence efforts and political intrigue.

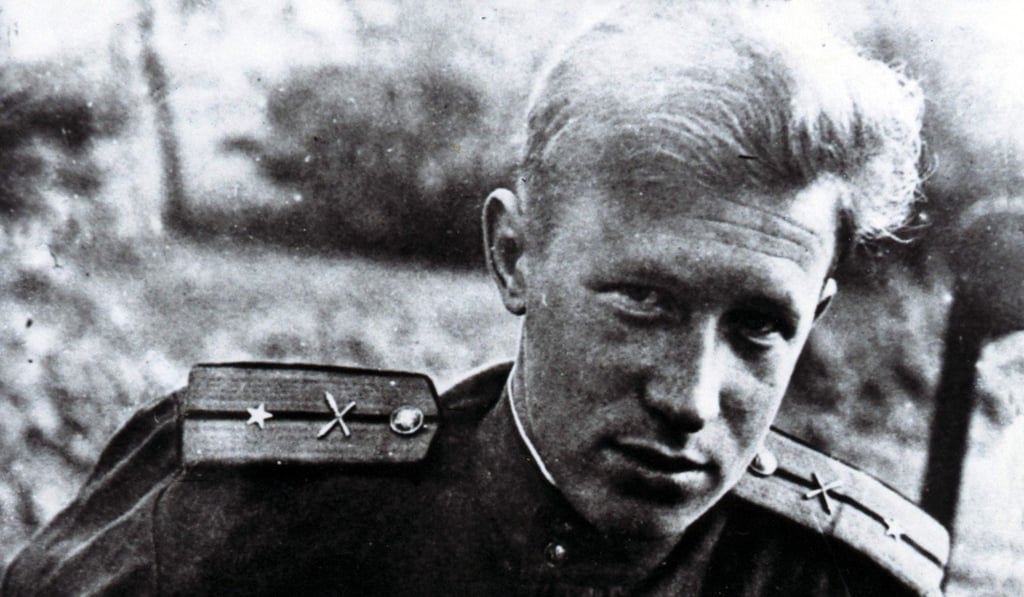

At the helm of their organisation, a secretive wing of the KGB known as Directorate S, was a balding man with the rank of major general and the name of Yuri Drozdov. A square-jawed World War II veteran who led assaults in Afghanistan and helped arrange a high-profile spy exchange in 1960s Berlin, he died June 21 at 91.

The Foreign Intelligence Service, a KGB successor agency known as the SVR, announced his death but did not provide additional details.

In my KGB career I had much experience at getting enemies to do my will, and I thought this would be very useful in business

Drozdov oversaw the KGB’s illegals program - its name distinguished it from the agency’s “legal” spy program, in which agents maintained diplomatic connections to the Soviet motherland - from 1979 until 1991, shortly before the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It was the capstone of an intelligence career that spanned nearly the entire Cold War, from a stint on the “bridge of spies” in Berlin to an undercover position in China at the start of Mao Zedong’s bloody Cultural Revolution.

Yet despite spending much of his career behind the scenes, Drozdov was not afraid to involve himself in “wet affairs”, the euphemistic KGB term for assassinations, beatings, poison-tipped umbrella murders and similar acts of hand-dirtying.

It was Drozdov who led KGB forces in the December 1979 assault on the palace of Afghan President Hafizullah Amin, a 43-minute surprise attack that resulted in Amin’s death and launched a Soviet invasion of the country. The operation resulted in the deaths of 55 Soviet operatives, 37 of them from an aircraft crash, and of 180 Afghans, according to an account by Jonathan Haslam, a historian of the Soviet Union’s foreign policy and intelligence efforts. One Russian leader later described the attack as “perfect” and “absolutely unprecedented.”