Analysis | Russian Communist candidate has zero chance against President Vladimir Putin … but a man can dream

Although Putin is overwhelmingly favoured to win a new six-year term March 18, Pavel Grudinin has as good a chance as anyone to come in second

There’s a Russian candidate for president who is wildly popular on YouTube, where he slams the policies of President Vladimir Putin.

He has a nationwide political machine and a constituency of millions who are fed up with the current Kremlin occupant and his oligarch friends.

Although Putin is overwhelmingly favoured to win a new six-year term March 18, this contender has as good a chance as anyone to come in second.

And no, his name is not Alexei Navalny.

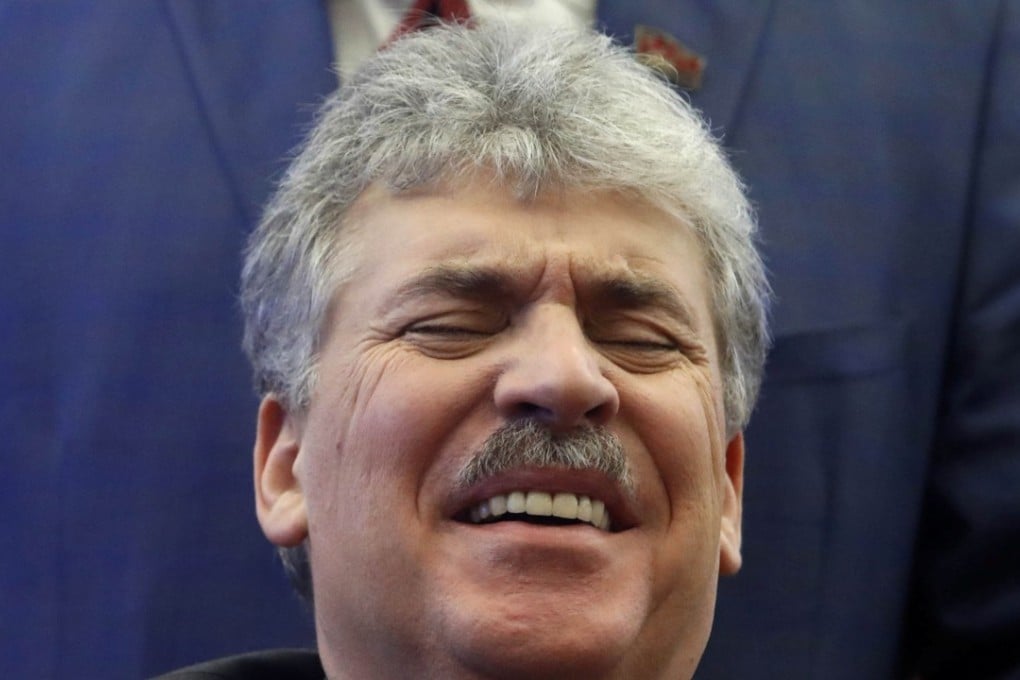

It is Pavel Grudinin, the surprise nominee of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, named last month to replace Gennady Zyuganov, the party’s 73-year-old leader and four-time presidential runner-up.

Grudinin, 57, has steered a formerly state-run produce farm outside Moscow into a flourishing business he markets as a showcase for the socialism he’d bring back to Russia.

Like Navalny, the 41-year-old anti-corruption activist excluded from the ballot by Russia’s election commission last month, Grudinin appeals to Russians tired of Putin after his 18 years in power.