Coronavirus pandemic puts Russia’s strongman Putin to the test

- Covid-19 has created obstacles for Vladimir Putin’s bid to consolidate power, extend time in office

- Constitutional referendum was set to be held this week, but was postponed because of the growing number of cases in Russia

Instead, Moscow’s streets have been emptied: a jarring turn of events for a bustling city of nearly 12 million people.

Wednesday’s vote was postponed last month as part of a wave of measures meant to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus that has infected thousands, including a citywide lockdown in Moscow and the implementation of increasingly authoritarian surveillance networks.

Xi and Putin show united front as China criticised over coronavirus handling

But while these measures have been positioned as a way of maintaining control in a time of uncertainty, the developing pandemic has created an existential crisis for Putin, one that damages his image at a moment when public support is crucial for consolidating his regime well into the future.

The Russian constitution has given the president extensive powers since 1993, when Boris Yeltsin shored up his capacities in the wake of the constitutional crisis with the parliament that was resolved with military intervention. Since that time, the only official change was the 2008 decision to extend the term of office from four years to six.

Interestingly, Putin’s original intentions, back when the constitutional referendum was announced on January 15, were to limit the influence of the president. Both parliament and the prime minister would be given greater powers, and all governing organs would be placed under the advisory influence of the State Council, a political body to which Putin could retreat should he step back from the presidential role.

Mikhail who? Putin’s pick for Russia PM is a political nobody

This changed dramatically on March 10, when a motion was presented in parliament to reset Putin’s presidential terms to zero, effectively allowing him to run for another two terms (12 years total) beginning in 2024. This would require a change in the constitution and so was added to the list of reforms to be voted on during the referendum. The previous amendments limiting presidential powers were abandoned.

This proved a controversial move. Dmitri Makarov, a human rights monitor in Moscow, said that “the ‘All-Russian Vote’ is actually a referendum to support the Putin regime”.

In addition to extended terms in office, the president would have the right to dismiss judges, dissolve parliament and effectively veto laws.

This about-face reflects the increased amount of instability that has emerged since January. Kremlin press secretary Dmitry Peskov said that Putin’s decision to accept the potential new powers was a response to “extreme turbulence in the world”, which may refer not only to the virus but also to the ongoing oil crisis and Russia’s military engagement with Turkey in Syria.

The new referendum, in other words, was an attempt to formalise total control in a steady set of hands. “Our competitive advantage is not oil and gas,” said State Duma chairman Vyacheslav Volodin, just days after the changes were swept through parliament. “It’s Vladimir Putin.”

But Putin’s legacy is also at stake.

“He isn’t holding onto power, but rather onto his place in history,” political analyst Konstantin Kalachev told Russian outlet The Bell. “He is waiting for an opportunity … to be able to say: ‘I built the foundations and I created the conditions for growth, now let someone else continue what I started’.”

Russia had been initially quick to respond as the epidemic was emerging in neighbouring China, with Russia closing the border in January, but it lagged behind European countries in imposing domestic measures.

When the coronavirus started making its way across the country, Putin used it to improve his standing. He made numerous statements claiming that things were under control. The fact that Europe and America were heavily affected played to Kremlin propaganda, which was reported to have proliferated with narratives on how better prepared Russia was for the crisis than the West. Symbolic gestures, like sending medical supplies to the US or Italy, were promoted in the news. Authoritarian surveillance measures were lauded as ways to crack down on quarantine violators.

But it wasn’t long, however, before cracks in this veneer began to show.

While the official line for weeks was that the situation was contained, an emergency coronavirus hospital was ordered to be built just outside Moscow. Self-isolation measures and calls for non-essential businesses to be closed proved unpopular and thus, to keep from spoiling Putin’s image, were delegated to regional governors and, notably, Moscow mayor Sergey Sobyanin.

Putin warns of ‘extraordinary’ coronavirus crisis in Russia

This raised eyebrows within the country. “Their response was to delegate key decisions to a regional level as well as for the president to address the population several times, saying everything will pass,” said Makarov. “Which, in my opinion, looks like they’re trying to shift responsibility for measures that were unpopular and weren’t well thought out.”

While mayors and governors are careful not to cross the president publicly, the worsening situation in Moscow forced Sobyanin to confront Putin with the true scale of the outbreak. “The real number of those who are sick is significantly higher” than the official statistics, he told the president at the end of March.

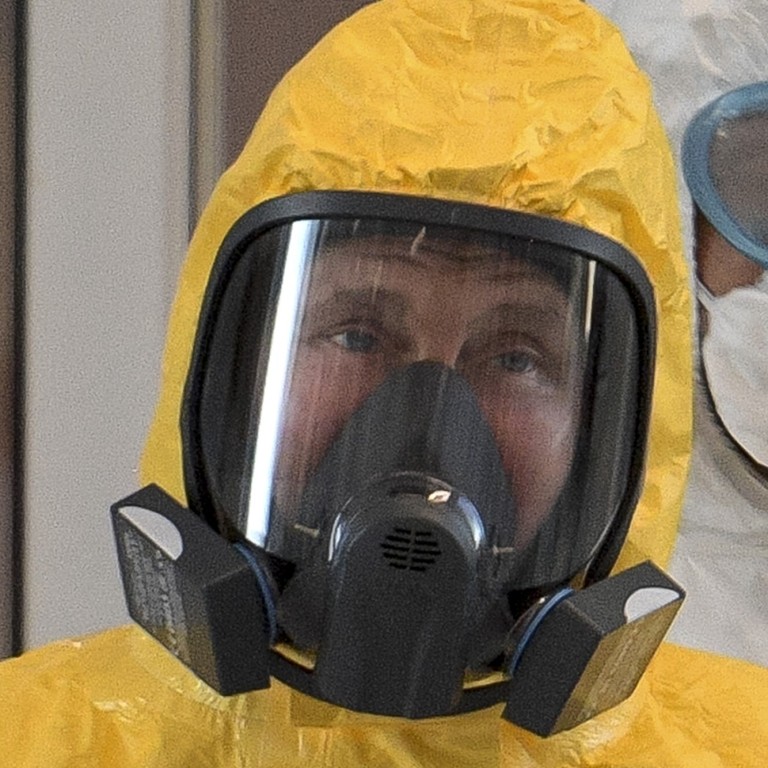

In another public relations disaster, a photo of Putin shaking hands with a prominent doctor, without any protective gear, was published widely after the doctor himself had contracted the virus. The president subsequently announced his own self-isolation.

When Putin did change his tune, appearing publicly last week with an address to the nation describing the pandemic’s seriousness, he declared his readiness to deploy the army if necessary. He also promoted the increasing lockdown measures, particularly in Moscow, as an important step in reducing infections.

Vladimir Putin’s 20 years on the global stage

But even these began to backfire. The long-awaited digital pass system, implemented last Wednesday to allow Moscow residents to move around the city, led to an infrastructural disaster and huge crowds in the city’s metro system, making social distancing impossible. The president was late to his address that day, where he avoided the topic and spoke mainly about supporting small businesses.

A less obvious, but no less important, blow came as Putin postponed the May 9 Victory Day Parade, Russia’s largest public event, which celebrates the 75th anniversary of the nation’s victory in World War II. Memorialising the victory is a key narrative in Kremlin propaganda, and has been used to justify actions such as the annexation of the Crimean peninsula in 2014, which itself was a huge boost to Putin’s domestic ratings.

Putin may have planned the year in hopes of consolidating power, celebrating the anniversary of Russian victory and ushering in the next phase of his life in public office, but instead he’s caught in a struggle with an invisible enemy that is difficult to contain.

“The peak of the disease spread is still ahead,” Putin said this week.

By Wednesday, Russia had recorded 5,236 new coronavirus cases in 24 hours, bringing the national tally to 57,999, with more than 30,000 cases reported in Moscow. The national death toll was 513.

Russian leader Vladimir Putin keeps shirt on for his 2020 calendar

Russian officials have predicted that the number of cases in the country could plateau next month as most of the regions are under quarantine.

“The Kremlin would probably like to have introduced total control measures, but it didn’t turn out to be capable of this,” Makarov said. “They would have also had to keep in mind how this would look to everyday citizens, especially on the eve of the all-Russian vote.”

With the ongoing crisis unfolding across the world, he and other world leaders are having to adopt new strategies to cope and maintain their hold on power.

While the pandemic lasts, however, parades are tools Putin certainly will not be able to use.

And the referendum? Peskov, the Kremlin’s spokesman said a new date for the vote would be “decided as the situation develops”.

Additional reporting by DPA