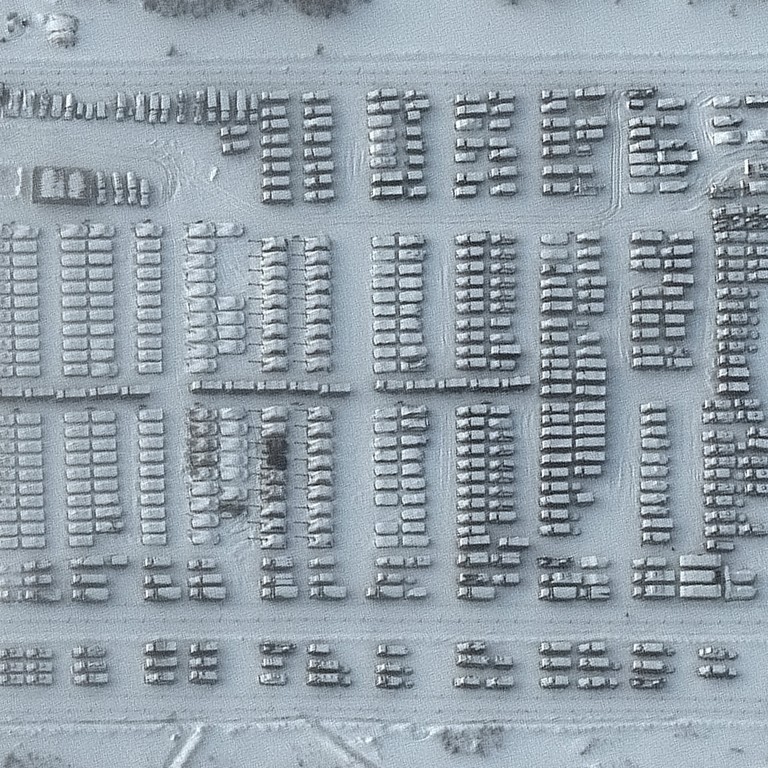

Ukraine crisis: satellite photos give bird’s-eye view of Russian military positions

- High-resolution photos from commercial satellite companies show Russian positions

- Images confirmed that Russian forces are arrayed within striking distances of Ukraine

Widely available commercial satellite imagery of Russian troop positions bracketing Ukraine provides a bird’s-eye view of an international crisis as it unfolds. But the pictures, while dramatic, have limitations.

High-resolution photos from commercial satellite companies like Maxar in recent days showed Russian troop assembly areas, airfields, artillery positions and other activities on the Russian side of the Ukrainian border and in southern Belarus as well as on the Crimean Peninsula, which Russia seized from Ukraine in 2014.

The images confirmed what US and other Western officials have been saying: Russian forces are arrayed within striking distances of Ukraine. But they could not provide conclusive information about net additions or subtractions of Russian forces or reveal when or whether an invasion of Ukraine would happen. In such a fluid crisis, even day-old satellite photos might miss significant changes on the ground.

Western officials, citing their own sources of information, have disputed Moscow’s claim that it pulled back some forces, and they asserted that the Russians added as many as 7,000 more troops in recent days. Commercial satellite images alone cannot provide that level of detail in real time or allow broader conclusions about the Russian build-up, such as the total number of its deployed troops.

Nato: Russia could invade Ukraine with little or no warning, new shelling reports

“What you get out of an outfit like Maxar is very good information but not as precise or as timely as that provided to US national leadership” through the government’s own classified collection systems, said James Stavridis, a retired US Navy admiral who served as the top Nato commander in Europe from 2009 to 2013. “Therefore I would strongly bias my views toward what is being reported by the US government.”

Before commercial satellite imagery became widely available and distributed online, Russia, the United States and other powers could largely hide their most sensitive military movements and deployments from near real-time public scrutiny.

Although the public now can obtain a better view, this imagery is not nearly as precise, comprehensive or immediate as what the US military can collect.

Ukraine crisis: the basic weapon Russia uses to deflect, belittle rivals

The US military and intelligence agencies can piece together a better picture of what’s happening by combining satellite imagery with real-time video as well as electronic information scooped up by aircraft such as the US Air Force’s RC-135 Rivet Joint, not to mention information gathered from human sources.

The US government also contracts with commercial satellite firms for imagery as a supplement and to ease the strain on imagery collection systems needed for other top-priority information.

Commercial satellite images, as a snapshot in time, do not provide indisputable evidence of exactly what the Russian military is doing or why.

“You can see something on a base, that looks like a base that has a lot of activity,” and reach some broad conclusions. “But in terms of what’s being done there, and what the units are – that takes a lot more intel,” said Hans Kristensen, who has extensively analysed commercial satellite imagery to study nuclear weapons developments in China and elsewhere in his position as director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists.