Ukraine: Putin keeps loyalty of Russian political elite despite outcry over war

- Despite international indignation over invasion of Ukraine and major sanctions, no apparent outbreak of dissent in Putin’s inner circle

- ‘Many believe the war is a mistake but no one is able to act, everyone is focused on their own survival’, says analyst

President Vladimir Putin is for now holding on to the public loyalty of Russia’s political elite, despite the international outcry over the invasion of Ukraine and unprecedented sanctions.

Russian artists and heavyweight media figures have spoken out against the war and even billionaire oligarchs have offered veiled criticism.

But after almost a month of fighting, there has been no apparent outbreak of dissent from within Putin’s inner circle or among political heavyweights inside the country.

“There has been no sign of a split” within the ruling class, said Tatiana Stanovaya, founder of the R.Politik political analysis firm.

“There is a full consensus, albeit possibly with differences on tactics,” she added.

She said a distinction had to be drawn between having reservations about the invasion and being ready to act.

“People are in shock and many believe this is a mistake. But no one is able to act. Everyone is focused on their own survival.”

Western diplomatic sources say despite the crushing impact of sanctions on the Russian economy, there is no sign yet that this will translate into political change.

The main domestic criticism of the invasion, according to Stanovaya, comes from “peripheral” forces on the radical right who think it is not proceeding aggressively enough.

Russian state television dominates the narrative, presenting what the Kremlin calls a “special military operation” in Ukraine as a heroic mission against Western aggression.

“It’s no real surprise that we haven’t yet seen dramatic, public splits within the ruling elite,” said Ben Noble, associate professor of Russian politics at University College London and co-author of a recent book “Navalny: Putin’s Nemesis, Russia’s Future?”.

“Vladimir Putin has cultivated a system in which he is surrounded by super-loyalists who share his world view of a West out to destroy Russia, or those who are too afraid to voice their dissent,” he said.

On February 21, three days before the invasion began, Putin summoned the political leadership to the Kremlin for a security council to discuss recognising pro-Moscow breakaway regions in Ukraine as independent.

One by one, in a theatrical show of unity, the 12 men and one woman lined up to back the move to recognise the Donetsk and Luhansk regions as independent, a move now seen as heralding the war.

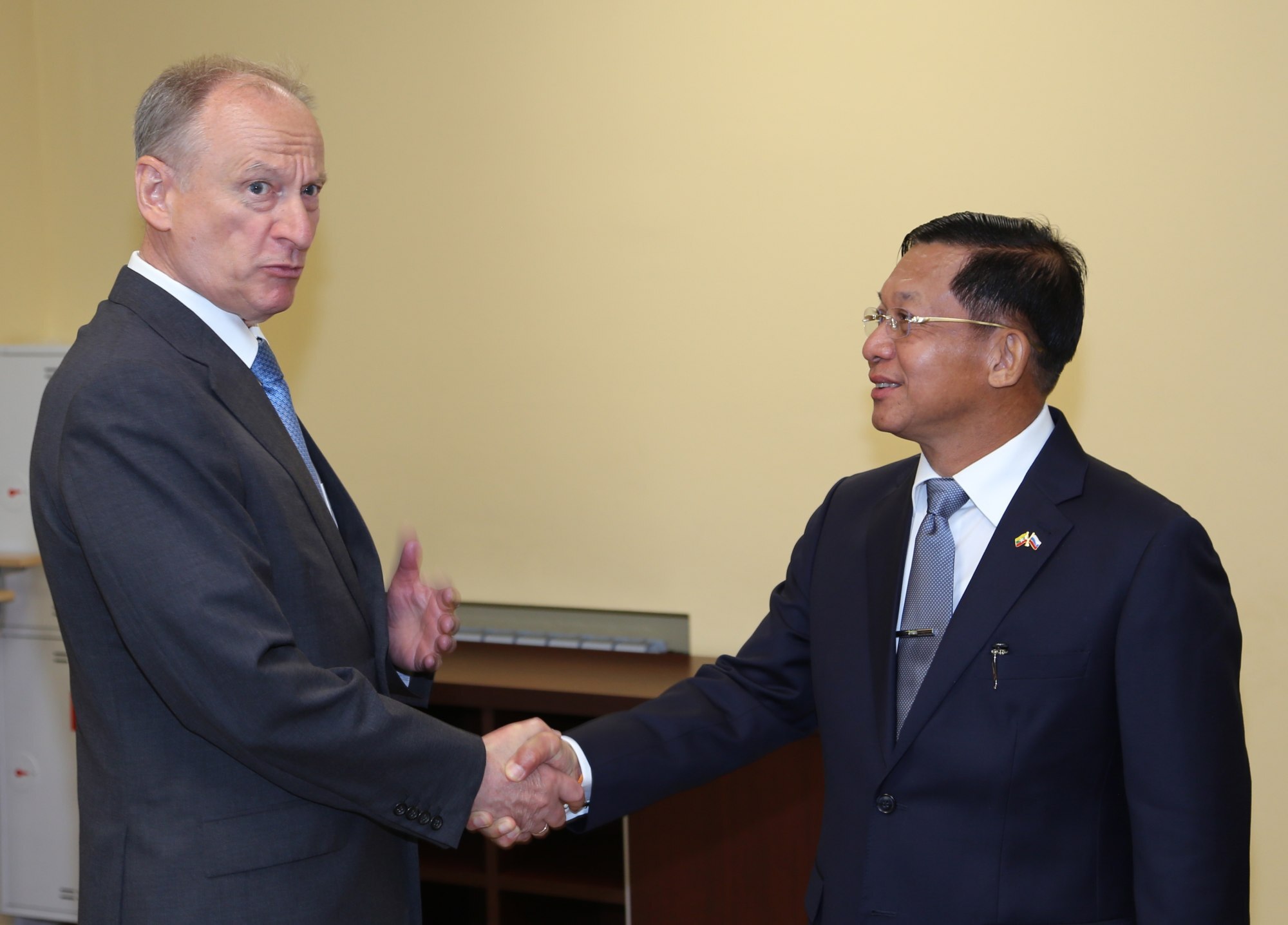

Those present at the meeting included the three men who Western security sources believe make up Putin’s tightest inner circle – Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu, National Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and Federal Security Service (FSB) chief Alexander Bortnikov.

There has not been the slightest murmur of dissent from those who attended or even from more low-ranking officials.

Virtually the only current or former insider to have broken ranks is the former Kremlin aide and ex-deputy prime minister Arkady Dvorkovich, also head of the main world chess body.

He came out against the war in a US magazine interview and stepped down from his post leading an entrepreneurship foundation.

From other liberal leaning ex-Kremlin figures, like the former finance minister Alexei Kudrin, now head of Russia’s audit chamber, there has simply been silence.

Putin considering using chemical, biological weapons in Ukraine: Biden

There was speculation over the future of economist and central bank head Elvira Nabiullina.

She was photographed looking dejected at a Kremlin meeting and posted a cryptic video, in which she acknowledged the Russian economy was in an “extreme” situation and said, “We all very much would have liked this not to have happened.”

But Putin this week asked parliament to nominate her for another term, apparently scotching rumours she could resign in protest at the war.

There have been murmurs of concern from oligarchs who stand to lose massively from the invasion, such as the magnates Oleg Deripaska and Mikhail Fridman, who have both made cautious comments promoting peace.

On March 3, the board of Russia’s largest privately-owned energy company, oil giant Lukoil, also called for an end to the conflict.

Noble added that many members of the elite were shocked by the invasion, as the vast majority “had not been involved in the decision-making process” and believed Putin was planning brinkmanship rather than invasion.

“However, it’s one thing to call for peace; it’s quite another to criticise Putin directly,” he said.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)