Sydney H. Schanberg, whose coverage of Cambodia’s ‘Killing Fields’ won Pulitzer, dies at 82

Sydney H. Schanberg, a foreign correspondent for The New York Times whose courageous reports about Cambodia’s takeover by the brutal Khmer Rouge regime in 1975 earned him the Pulitzer Prize and formed the basis of the Academy Award-winning film The Killing Fields, died July 9 at a hospital in Poughkeepsie, New York. He was 82.

He had a heart attack on Tuesday, said his wife, Jane Freiman Schanberg.

Shouting and angry, they wave us out of the car, put guns to our heads and stomachs and order us to put our hands over our heads

In the early 1970s, while based in Singapore for the Times, Schanberg began to report from Cambodia, a onetime French protectorate across the border from Vietnam.

He provided the first major coverage of US bombing missions that ravaged the Cambodian countryside, including a 1973 attack when a B-52 dropped 20 tonnes of bombs on a remote village, leaving about 150 residents dead.

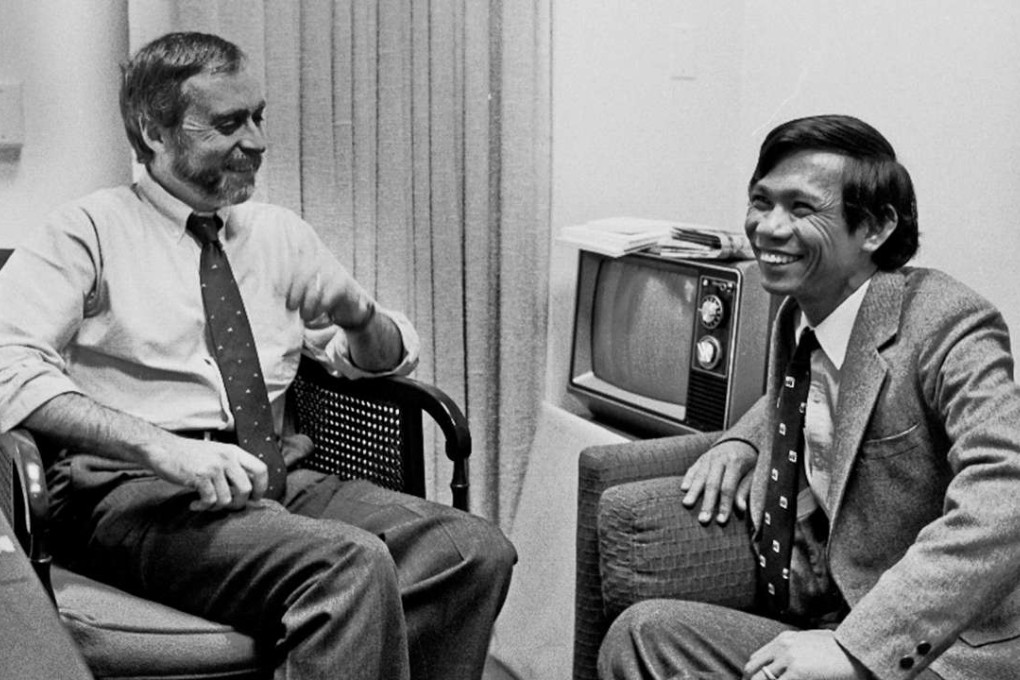

Schanberg’s partner in reporting was Dith Pran, a resourceful and multilingual Cambodian who served as his interpreter and guide. They became inseparable reporting partners, even as a communist-backed insurgency known as the Khmer Rouge began to close in on the capital city of Phnom Penh in early 1975.

As civil war enveloped the country, the US Embassy closed its doors on April 12. Schanberg refused orders from the Times to evacuate, choosing instead to take refuge with Dith at the French Embassy. As the only US reporter remaining in Cambodia, Schanberg visited hospitals, where the blood of Khmer Rouge victims flowed down the halls.