The Hongcouver | David and Goliath: a priceless Vancouver academic retires, after 45 years grappling with unaffordability

UBC geography professor David Ley has had a front-row seat to the epic transformation of a city

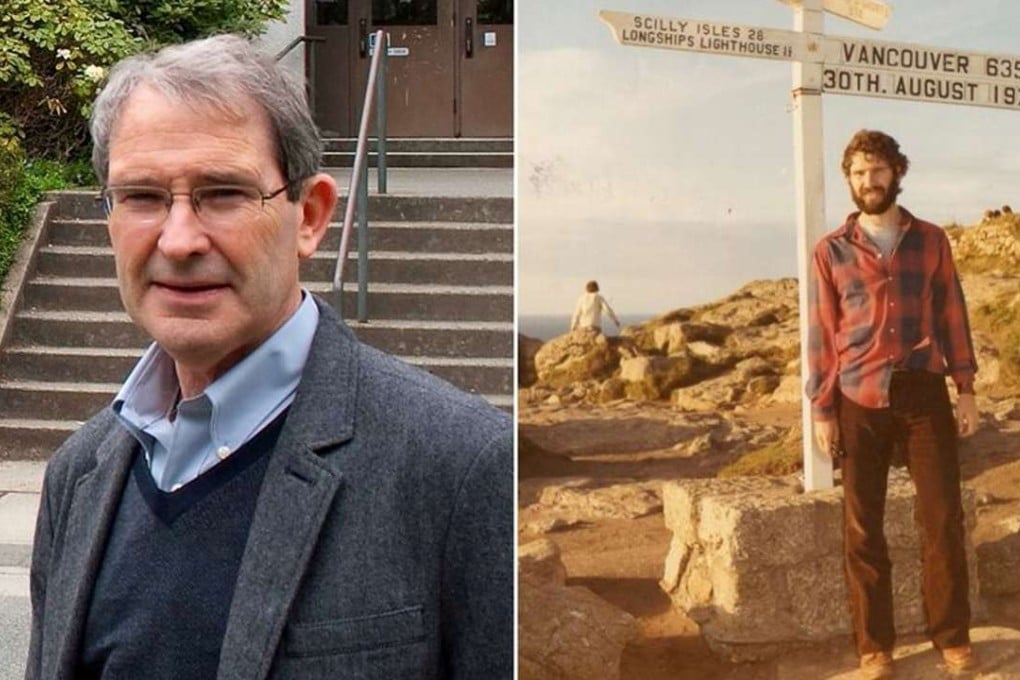

For more than 40 years, geographer David Ley has studied the Vancouver housing market, giving him a priceless academic perspective on the city’s struggle with now-epic unaffordability.

He arrived in the city in 1972, a bearded Briton in flared jeans, armed with an Oxford degree and an activist streak that had already taken him to Philadelphia. There he had both studied and sought to alleviate the stressed conditions of African American residents of poor neighbourhoods, where vacant homes struggled to find buyers for US$1. The former was conducted through his PhD work at Pennsylvania State University, the latter through volunteer work at a Presbyterian church.

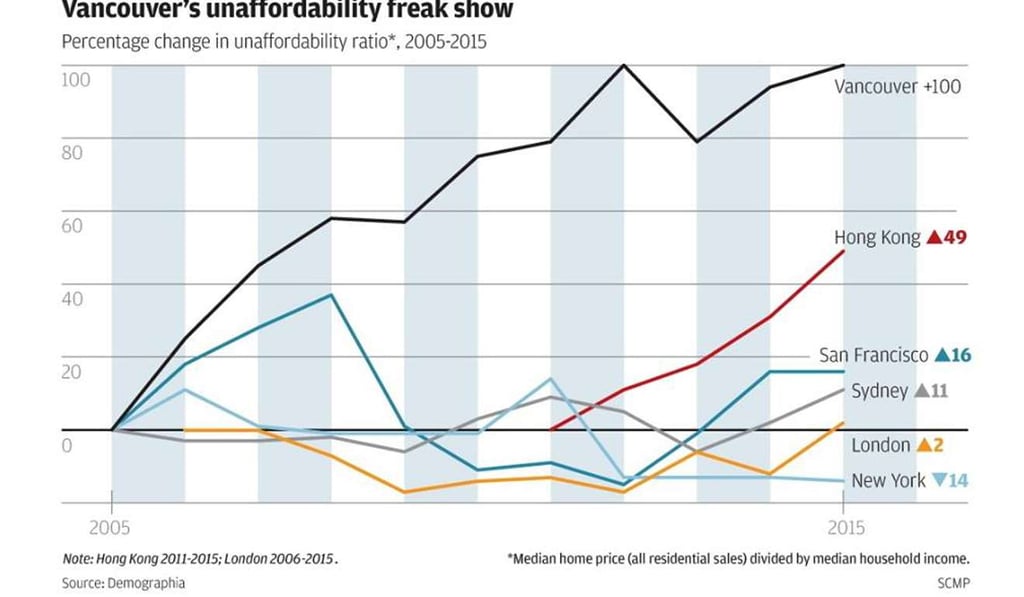

He landed here when the city was undergoing the first throes of gentrification, in contrast to the decay he had seen in Philadelphia. But he noticed victims here too - residents evicted from rooming houses to make way for the first condo developments. He could never have guessed that he was securing a ringside seat for one of the world’s most remarkable urban transformations, turning modest Vancouver into one of the planet’s most unaffordable cities, its residents alternately enriched and overwhelmed by waves of foreign capital. A global test case and basket case.

Now Ley, 69, perhaps the most significant academic voice in the unaffordability debate, is retiring from UBC; the former head of the geography department taught his last class this month and he officially retires at the end of the year after a research sabbatical. He continues to study real estate bubbles around the world, and there will likely be another book at the end of it, examining and comparing Vancouver, Hong Kong, Singapore, Sydney and London.