Tillerson under fire: US diplomats accuse their boss of breaking child soldiers law

‘Beyond contravening US law, this decision risks marring the credibility of a broad range of State Department reports’

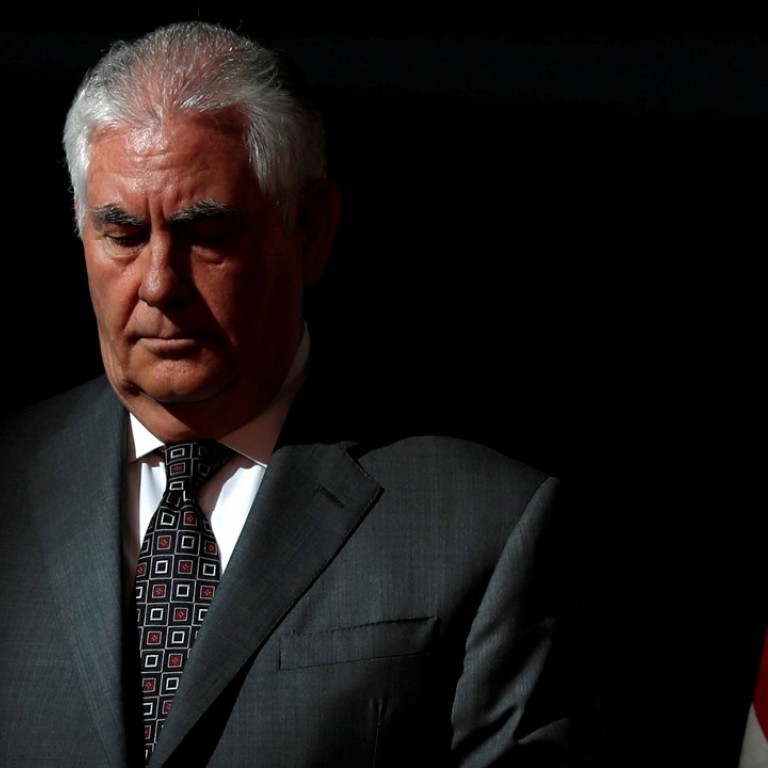

A group of about a dozen US State Department officials have taken the unusual step of formally accusing Secretary of State Rex Tillerson of violating a federal law designed to stop foreign militaries from enlisting child soldiers, according to internal documents.

A confidential State Department “dissent” memo not previously reported said Tillerson breached the Child Soldiers Prevention Act when he decided in June to exclude Iraq, Myanmar, and Afghanistan from a US list of offenders in the use of child soldiers. This was despite the department publicly acknowledging that children were being conscripted in those countries.

Keeping the countries off the annual list makes it easier to provide them with US military assistance. Iraq and Afghanistan are close allies in the fight against Islamist militants, while Myanmar is an emerging ally to offset China’s influence in Southeast Asia.

“Beyond contravening US law, this decision risks marring the credibility of a broad range of State Department reports and analyses and has weakened one of the US government’s primary diplomatic tools to deter governmental armed forces and government-supported armed groups from recruiting and using children in combat and support roles around the world,” said the July 28 memo.

Reuters reported in June that Tillerson had disregarded internal recommendations on Iraq, Myanmar and Afghanistan. The new documents reveal the scale of the opposition in the State Department, including the rare use of what is known as the “dissent channel,” which allows officials to object to policies without fear of reprisals.

The views expressed by the US officials illustrate ongoing tensions between career diplomats and the former chief of ExxonMobil Corp appointed by President Donald Trump to pursue an “America First” approach to diplomacy.

The child soldiers law passed in 2008 states that the US government must be satisfied that no children under the age of 18 “are recruited, conscripted or otherwise compelled to serve as child soldiers” for a country to be removed from the list. The statute extends specifically to government militaries and government-supported armed groups like militias.

The list currently includes the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Mali, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

“The Secretary thoroughly reviewed all of the information presented to him and made a determination about whether the facts presented justified a listing pursuant to the law,” a State Department spokesperson said when asked about the officials’ allegation that he had violated the law.

In a written response to the dissent memo on September 1, Tillerson adviser Brian Hook acknowledged that the three countries did use child soldiers. He said, however, it was necessary to distinguish between governments “making little or no effort to correct their child soldier violations … and those which are making sincere – if as yet incomplete – efforts.”

Hook made clear that America’s top diplomat used what he sees as his discretion to interpret the law.

Foreign militaries on the list are prohibited from receiving aid, training and weapons from Washington unless the White House issues a waiver based on US “national interest.” In 2016, under the Obama administration, both Iraq and Myanmar, as well as others such as Nigeria and Somalia, received waivers.

At times, the human rights community chided then-president Barack Obama for being too willing to issue waivers and exemptions, especially for governments that had security ties with Washington, instead of sanctioning more of those countries. “Human Rights Watch frequently criticised President Barack Obama for giving too many countries waivers, but the law has made a real difference,” Jo Becker, advocacy director for the group’s children’s rights division, wrote in June in a critique of Tillerson’s decision.

The dissenting US officials stressed that Tillerson’s decision to exclude Iraq, Afghanistan and Myanmar went a step further than the Obama administration’s waiver policy by contravening the law and effectively easing pressure on the countries to eradicate the use of child soldiers.

The officials acknowledged in the documents that those three countries had made progress. But in their reading of the law, they said that was not enough to be kept off a list that has been used to shame governments into completely eradicating the use of child soldiers.

Ben Cardin, senior Democrat on the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, wrote to Tillerson on Friday saying there were “serious concerns that the State Department may not be complying” with the law and that the secretary’s decision “sent a powerful message to these countries that they were receiving a pass on their unconscionable actions.”

Rachel Stohl, a senior associate at the Stimson Center think tank in Washington who focuses on children in armed conflict, said that by excluding the three countries from the list, “the Trump administration has further enabled perpetual human rights abusers.”