How is China persuading graft suspects in Canada to ‘surrender’? An embezzler’s disastrous deal offers clues

‘Don’t even think about it. Don’t even consider it. Not for a second. They can’t be trusted. Period’

For Chinese corruption suspect He Jian, seven years of life on the lam ended around 4.30pm on November 7 last year, on the stairs of Air China flight 992 from Vancouver.

But He was under no formal obligation to leave Canada, which has no extradition treaty with China. He faced no charges in Canada, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the federal force which has jurisdiction over Nanaimo, said it had no information on his case.

According to the CCDI, He had voluntarily “returned to China and surrendered himself to the police”.

Then on December 6, the CCDI announced another victory involving a British-Columbia-based suspect – former Yunnan tax collector Li Wenge had also returned and “surrendered”.

Li, accused of fraud in China, had been the target of a 2014 Canadian lawsuit which sought to freeze the sale of Richmond real estate supposedly purchased with about RMB12million (C$2.4million) in unpaid loans from a businesswoman in China. But like He, Li faced neither Canadian charges nor formal compulsion to return to China, and the RCMP (which polices Richmond) said it had no knowledge of his case, either.

However, their situation has a precedent that gives clues about how they were convinced to give in.

On New Year’s Day, 2012, accused embezzler Li Dongzhe (no relation to Li Wenge) arrived back in Beijing having voluntarily exited Canada – where he had been safe from deportation thanks to a “pre-removal risk assessment” by immigration authorities. They concluded he faced the prospect of torture in China. Li was a high-profile fugitive, accused of stealing more than US$100 million in one of the biggest bank frauds in Chinese history, and his prospects in China seemed dire.

So why surrender?

According to his Vancouver lawyer, Douglas Cannon, and documents reviewed by the South China Morning Post, Li engaged in lengthy negotiations with the Chinese consulate in Vancouver, including talks with a Chinese policeman based in Canada named You Xiaowen.

And Li thought he had struck a deal.

Cannon said Li thought the deal meant no more than 15 years jail, no jail time for his co-accused brother, and retention of assets Li said were unrelated to the alleged offences.

But instead, Li now serves a life sentence. His assets have been confiscated. His brother, Li Donghu, is serving a 25-year term.

Cannon, who has been retained to publicise the outcome of the case, has stark advice for any Chinese suspects in Canada considering striking a deal with Beijing for their return.

“Don’t even think about it. Don’t even consider it. Not for a second. They can’t be trusted. Period.”

‘The Li brothers trusted them and they should not have’

Of the 100 suspects on the CCDI’s “most wanted” list, issued as part of the Operation Skynet crackdown, 51 are known to have been arrested, including 13 who had reportedly been living in Canada.

In addition to Li and He, accused embezzler Wang Linjuan and alleged bribe-taker Li Shiqiao also returned from Canada in 2017. State media described both as having surrendered, in September and April respectively; it is not known where in Canada they had been living.

The South China Morning Post has no evidence of any of the suspects’ guilt or innocence.

“They managed to get the Li brothers back by lying through their teeth,” said Cannon. “The Li brothers trusted them and they should not have.”

Hebei businessman Li Dongzhe – whose failed deal with Chinese authorities was extensively reported by the Wall Street Journal in 2015 – was accused of embezzling US$113 million with the help of a corrupt Bank of China employee, Gao Shan. Both Li brothers fled to Vancouver on visitor visas on December 31, 2004, along with their families. Co-accused Gao Shan, now serving a 15-year sentence in China, had arrived in Canada the day before.

They managed to get the Li brothers back by lying through their teeth

The brothers’ financial affairs in Canada are described in a Vancouver police affidavit cited in their pre-removal risk assessment: as early as 2000, they started setting up bank accounts and companies, as well as buying BMW cars. In 2002, the brothers and their wives bought four luxury apartments in Coal Harbour’s Vantage tower in Downtown Vancouver, home to the Marriott Pinnacle Hotel. They also bought two nearby commercial units.

But in 2005, as Chinese authorities sought the Li brothers, the properties were sold for C$3.3 million in total. The registrations of the BMWs were terminated, as were all of the Canadian bank accounts (the Lis and their wives each had several). Properties, businesses, utilities, vehicle registrations and accounts were put in “nominee names” to avoid detection, the police affidavit said.

(Cannon said he could not confirm or deny anything about how he was being paid, nor discuss the brothers’ finances in Canada.)

The immigration department’s risk assessment concluded they were ineligible for consideration as refugees, and there was “evidence of serious reasons to show that the applicants have committed a serious crime in China.”

But it also found that they faced a risk of torture if expelled from Canada.

I shall not be handcuffed and no mandatory measures shall be taken against me. I shall be treated like a regular passenger

“They were excluded from making refugee claims but at the end of the day it didn’t make any difference because they were still recognised as people at risk,” said Cannon. “They were offered protection by the Canadian government … the bottom line is that they could not be returned to China against their will.”

Yet their circumstances were tenuous. Having previously been arrested for overstaying his visa, Li Dongzhe was living under a curfew and strict conditions that included an electronic monitoring bracelet. For some time, when he travelled around Vancouver, it had to be in Cannon’s company.

Weary of such restrictions, Li decided to try to cut a deal.

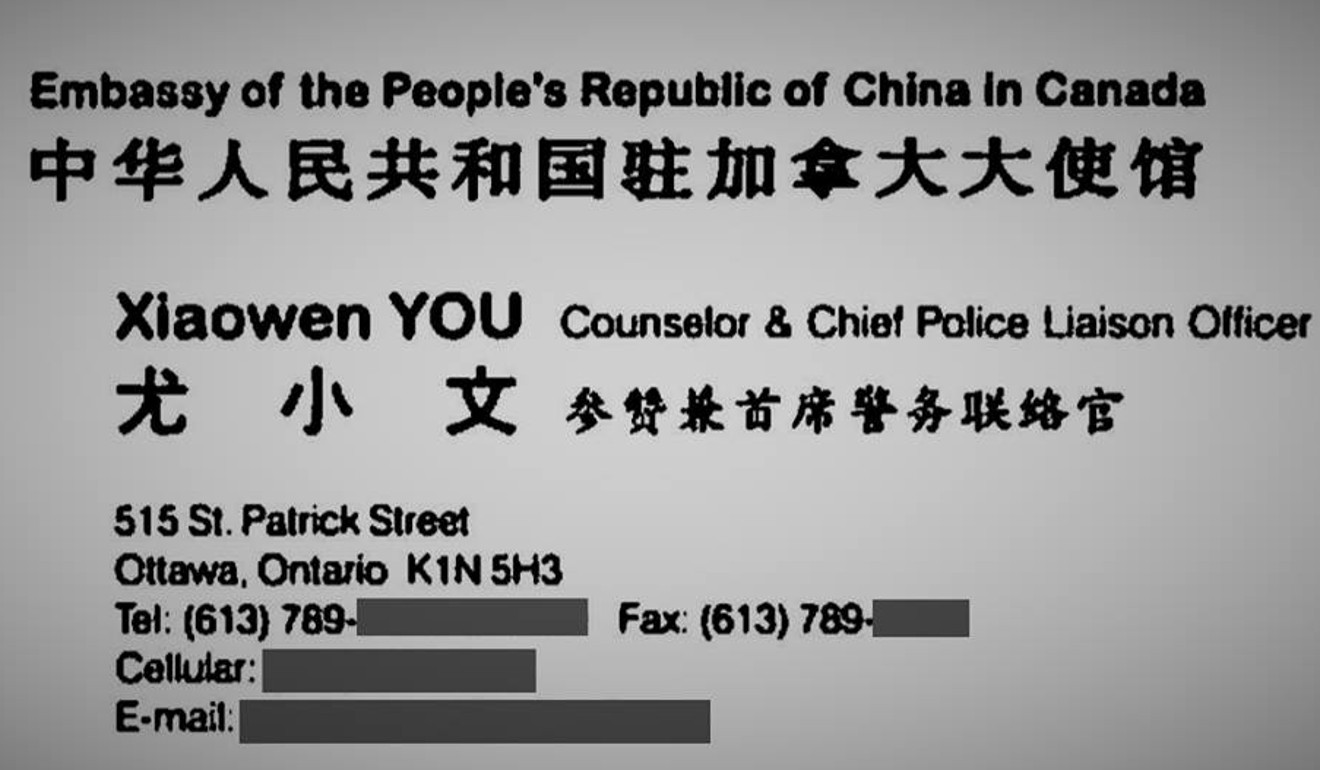

His primary contact was a Chinese policeman, You Xiaowen, officially based in the Chinese embassy in Ottawa. You’s business card, obtained by the SCMP, bears no official insignia but lists his title as “counselor and chief police liaison officer” for the embassy, along with phone numbers and a Hotmail address.

Cannon drove the Li brothers to their meetings at the Chinese consulate, which took place from mid-2011 and also sometimes involved co-accused Gao.

The lawyer did not take part in the negotiations and instead waited in the carpark, but Cannon did meet with Chinese officials, including the policeman You.

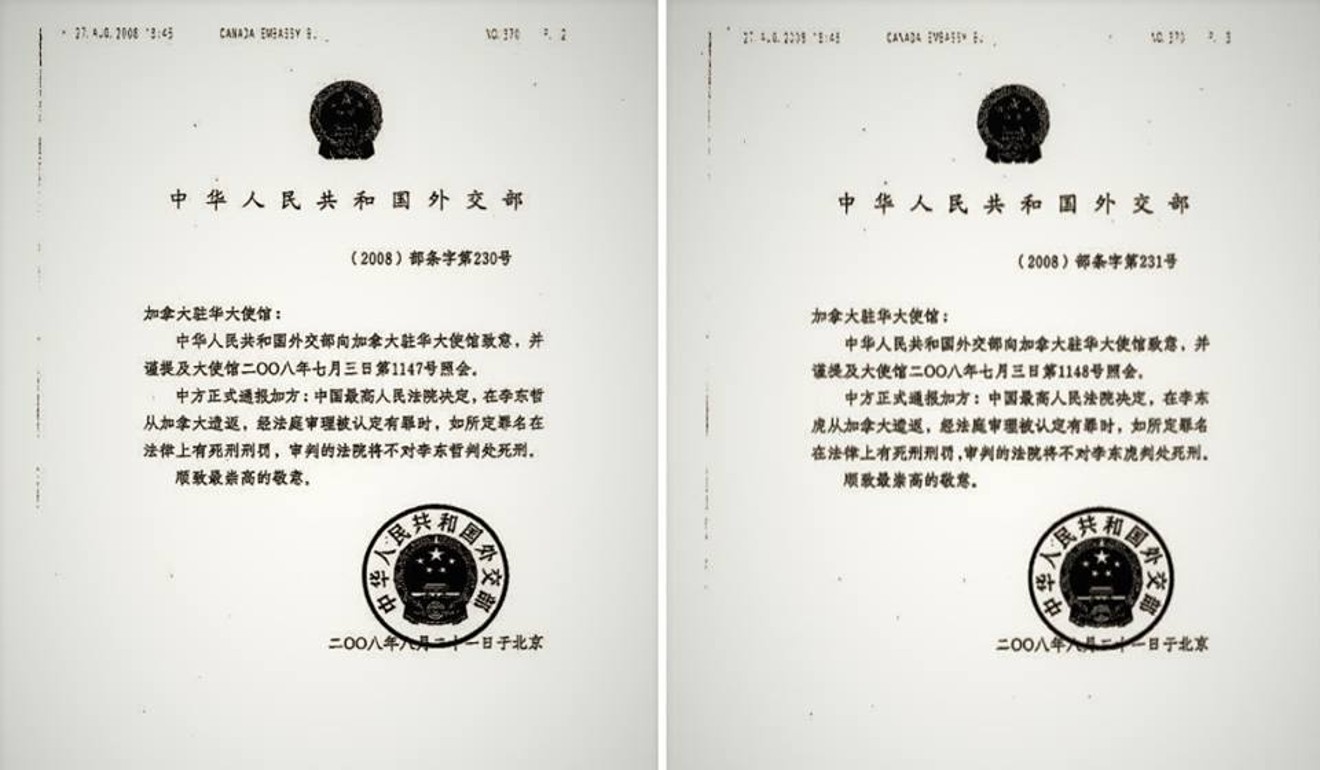

In 2008, in an attempt to secure the brothers’ repatriation, the Chinese government had already promised Canada that neither would be executed; it remains the only official undertaking in writing by the Chinese authorities regarding the case.

But the brothers’ private deal, according to Cannon, was that Li Dongzhe would face a 15-year maximum term, and that Li Donghu would not be jailed at all. No written record of this part of the supposed deal has ever been made public.

It was to be a two-stage process, said Cannon, with Li Donghu going back first, while Li Dongzhe waited to see how his brother was treated.

So happy was Li Dongzhe with the negotiations that he and fellow fugitive Gao posed for photos with the policeman You and then consul-general Liang Shugen on September 4, 2011, when the deal was discussed in the consulate on Vancouver’s Granville Street.

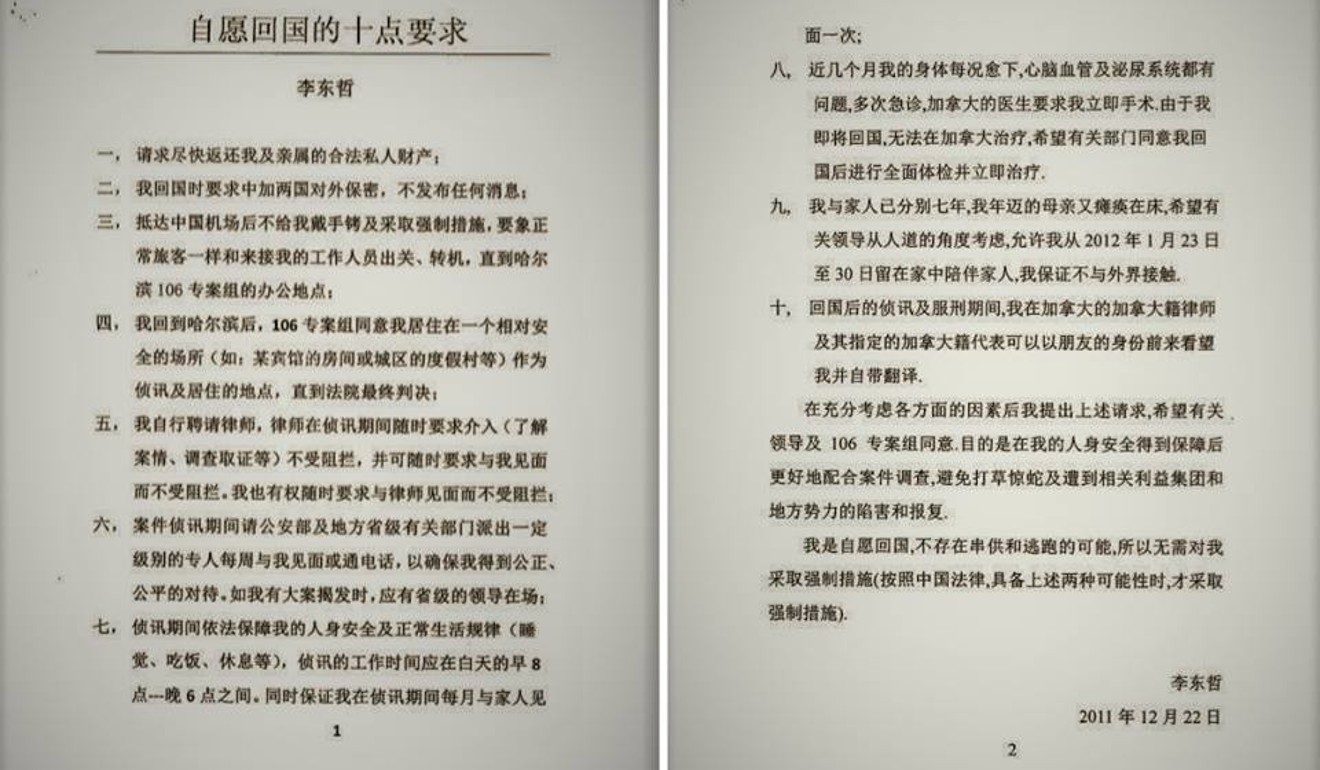

In addition to conditions about fair treatment and representation, it states “I shall not be handcuffed and no mandatory measures shall be taken against me. I shall be treated like a regular passenger”; and “after I return to Harbin, I will stay in a relatively safe place (eg a hotel room or a resort located in an urban area, etc) where investigation takes place”. Li also asks that he be allowed to spend the week of the Lunar New Year with his senile mother, and that his return to China be kept secret.

The document concludes by stating that Li is “returning to China voluntarily”.

Li Donghu had gone back to China in July 2011. When Li Dongzhe followed six months later, he was quietly arrested, according to plan.

All was going well until Gao returned to China in August 2012. It was then that “the Chinese government threw the Lis’ agreement out the window” and arrested Li Donghu, said Cannon.

“They [Chinese authorities] said, ‘we don’t care what you think we promised you. You’re both going to jail, and Dongzhe, you’re going to jail for life’.”

According to the Wall Street Journal, the deal struck in Vancouver was not even mentioned in the 166-page court ruling that condemned Li Dongzhe to jail for life.

“There was no doubt the Chinese government broke their promise,” said Cannon. “Not only leniency, but return of improperly seized assets. The biggest breach was the length of the jail term given to Dongzhe, and the fact that Donghu also went to jail. Donghu was never supposed to go to jail.”

A ‘missed opportunity’ for China?

Whether Chinese authorities negotiated with Li Wenge and He Jian before their return to China is not known, but it is clear that they were also under pressure.

In April 2017, the CCDI published their Canadian addresses, along with those of 20 other suspects around the world. Li was living on Barnard Drive in Richmond – the same street where he owned a house named in the 2014 Canadian lawsuit – while He Jian was living on Dover Road, Nanaimo.

Reporters for Vancouver’s Chinese-language media visited the supermarket in Richmond where Li worked, and knocked on the door of the Barnard Street home and another Richmond townhouse he owned.

When a reporter for the state Xinhua news agency visited He’s home in Nanaimo, the door was reportedly closed in their face and two people sped off in a black BMW and a black Mercedes.

Did Chinese authorities make deals with Li and He? The policeman You did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

And explanations offered by Chinese authorities have been vague.

Without directly referring to Li Wenge or He, Cannon said any suspect should be wary of promises made by the Chinese government to persuade them to surrender, and he had never seen China adhere to such deals. “I have only seen them have improper influence over people”, he said. By this he meant “pressure on family members, using threats, torture, threats of torture”.

Cannon said he could not say whether other people on the CCDI’s wanted list had contacted or retained his firm. “But I can tell you that I don’t have any clients right now who have retained me to speak publicly about the situation in the way that the Li brothers have.”

He said he regarded the Li brothers’ deal as a missed opportunity – for China.

“Not a single country in the world wants to be harbouring Chinese fugitives from Chinese justice. The only thing countries like Canada expect is that they be treated fairly,” Cannon said.

“There was a deal in place and it was breached. It proved to the world, once again, that the Chinese authorities cannot be trusted, not even for a second.”

*

The Hongcouver blog is devoted to the hybrid culture of its namesake cities: Hong Kong and Vancouver. All story ideas and comments are welcome. Connect with me by email [email protected] or on Twitter, @ianjamesyoung70.