In Vancouver, at the heart of Canada’s fentanyl crisis, extreme ‘harm reduction’ efforts that may guide US

‘To save lives, you need a table, chairs and some volunteers. We literally popped it up in one day. And then you have people saving lives. Immediately’

Beneath a blue tarp that blocks out a grey sky, Jordanna Coleman inhales the smoke from a heated mixture of heroin and methamphetamine, sucking the addictive vapour deep into her lungs.

The drugs and pipe, acquired elsewhere, are hers. But the shelter, the equipment she uses to prepare her fix and the volunteers standing by to respond if she overdoses are provided by a small non-profit group. Funding and supplies come from the city of Vancouver and the province of British Columbia.

“I was outside. It’s warmer in here,” says Coleman, 22, although the tent is open to the damp and chill of a western Canadian winter. “It’s just safer.”

In barely a year, five sites like this one have opened within a few blocks of one another to contend with a surge of fentanyl on Vancouver’s streets. In December, the organisation that runs this location, the Overdose Prevention Society, took over a vacant building next door, giving users a clean indoor place to inject drugs. There are 29 similar sites in British Columbia, the epicentre of Canada’s drug crisis, and more across the country.

“To save lives, you need a table, chairs and some volunteers,” said Sarah Blyth, the manager here. “We literally popped it up in one day. And then you have people saving lives. Immediately.”

Look at Vancouver, it’s tried every bad policy you can try. This is another step in that whole policy that has made Vancouver a nightmare

As fentanyl rampages across North America, several US cities have announced that they will open the first supervised drug-consumption sites like those in Canada. Their plans illustrate the gulf between the two nations: While Justin Trudeau’s government is doubling down on its “harm reduction” approach, any US organisation that tries to follow suit would be violating federal law and risking a confrontation with the Justice Department.

US researchers say that at least one underground site is operating on American soil, and they predict that a public operation will open despite the potential consequences.

“That is the way that drug policy issues have moved forward in this country [over the] last 25 years,” said Alex Kral, an epidemiologist at the think tank RTI International, who has studied supervised drug consumption. Cities enduring the deaths, disease, crime and cost of drug epidemics have taken the lead in handing out free needles and distributing the overdose antidote naloxone – sometimes after legal battles.

San Francisco plans to add supervised injection services to an existing community health facility. Those could start as soon as July 1.

Canada’s plans do not stop at supervised injection. Some sites now test users’ drugs for fentanyl, and some are aiming to provide prescription opioids from vending machines.

The most far-reaching intervention is just two blocks from the pop-up site, where the Providence Crosstown Clinic provides 130 of the city’s most hard-core drug users with pharmaceutical-grade heroin and other narcotics. Users come to inject themselves as often as three times a day, and some also swallow a morphine tablet to carry them through the night.

Freed of the need to steal, beg and trade sex for drug money, some now have apartments and jobs. The clinic, run by a medical centre, hopes to add 50 more clients soon.

Research shows that the approach, like supervised drug consumption, saves lives, cuts criminal justice and health care costs, limits the spread of diseases such as HIV and helps reduce used needles and other debris in its immediate neighbourhood. A similar facility recently opened in Ottawa, and Canada has loosened requirements to encourage still others.

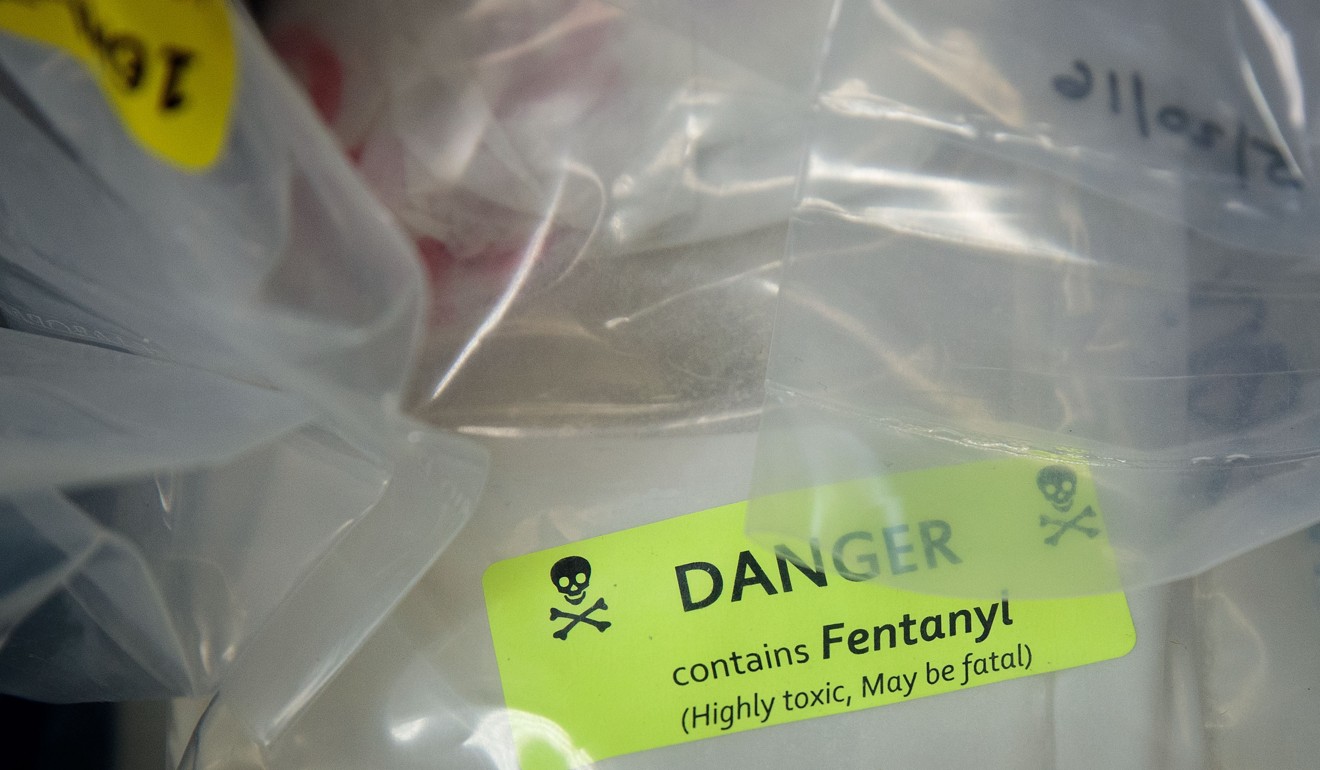

But British Columbia’s programmes have not blunted its opioid crisis. Overdose deaths have skyrocketed from fewer than 400 in 2014, when fentanyl became widely available on the street, to more than 1,400 in 2017. Eighty-one per cent of last year’s deaths involved fentanyl.

Critics said that statistic speaks to the futility of harm reduction. “To say the best we can do is to revive people who are victims and are going to be victims again … is reprehensible,” said John Walters, drug tsar under President George W. Bush and now chief operating officer of the Hudson Institute, a conservative think-tank in Washington.

Walters favours a dramatic expansion of drug treatment in the United States, which recorded 42,000 opioid deaths in 2016, coupled with a much more concerted effort to keep drugs such as fentanyl out of the country. He questions the rigour of the academic studies that support harm reduction. And he believes that normalisation and tolerance of drug use are reasons that addicts crowd the streets of this city’s small Downtown Eastside district.

“Look at Vancouver, it’s tried every bad policy you can try,” Walters said. “This is another step in that whole policy that has made Vancouver a nightmare.”

Drug smokers like Coleman are still restricted to the Overdose Prevention Society’s outdoor tents because the new building, a former grocery, has no ventilation system. It is home mostly to injection drug users. A long, narrow main room is nearly bare except for 13 stainless-steel tables and some posters on the walls. Red partitions divide the rest of the floor, making space for a couple of desks, a cot where workers can calm down after resuscitating an overdose victim, and supplies piled high in boxes.

The most critical are oxygen and naloxone, the antidote that has saved countless lives. In the 30 years that supervised sites have been open in Europe, and the 15 years that they have existed in Canada, no site has suffered an overdose death, Kral said.

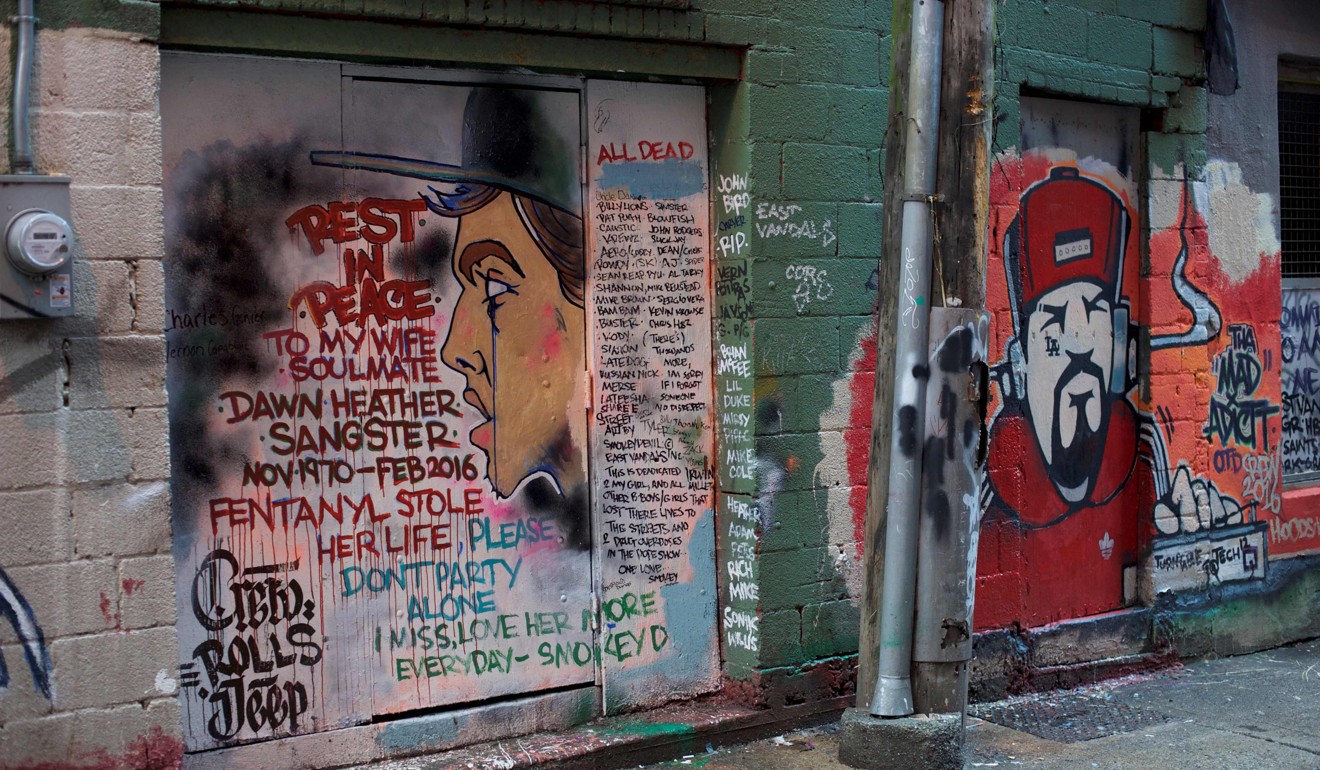

Users enter here through a guarded door off a back alley that used to be the scene of widespread drug use, dealing and prostitution. A small street shrine to a dead woman sits just outside the entrance.

From a small table of supplies they pick up what they need: syringes, matches, elastic strips to tie off veins, water to dilute drugs, small squares of foil, tiny tins for cooking heroin. Also available are condoms and lube.

Some of the volunteers who greet them are current or former users themselves. They usher clients to the tables. On a clipboard, one staff member logs names (usually aliases), gender, the drugs being used and the time a person comes in. Between the indoor and outdoor sections, 300 to 700 people show up daily. The largest crowds are on days when welfare payments arrive.

The pop-up was born of necessity in late 2016, when fentanyl was overwhelming the neighbourhood and a 15-year-old supervised-use programme. Overdoses on the street would send panicked bystanders to a nearby open-air market to find naloxone or call an ambulance.

“If there was an overdose, they would come running to the market and we would have Narcan ready,” Blyth said, using the antidote’s brand name. “Then it became so frequent that it was happening all the time. We had no choice really.” A GoFundMe campaign started the tent facility. Aid from the government followed.

The organisers acknowledge that their main goal is just to keep people alive, though they have seen a few clients get into treatment and off drugs.

“If these services didn’t exist, trust me, it would have been a catastrophe, especially in the past year and a half, when the fentanyl crisis spiked,” said RonnieGrigg, a large, soft-spoken man with a chest-length beard who helps manage the site. In the past three years, Grigg said, 100 people he knew have died of overdoses.

At the Providence Crosstown Clinic a short walk along West Hastings Street, some users measure their addictions in decades.

Nothing else has worked for these men and women, who clinically are in the grip of “severe opioid disorder.” Methadone has proven ineffective, as have therapeutic approaches such as 12-step programmes. Most of them no longer feel any pleasure from the drugs; they take them simply to function and prevent severe withdrawal symptoms.

“It makes me feel normal,” explained a 52-year-old woman named Lori, who did not want her last name used.

Other than more than a decade on drugs, Lori leads a fairly unremarkable life. She has two grown children who don’t know about her twice-a-day clinic visits. She is married and holds a part-time job in a call centre, taking customer service complaints. She is clearheaded and contemplative.

Over time, the cost of her habit reached US$200 a day. In 2011, she heard about a research study at the clinic and began getting her drugs there.

“Thank God, because I would be on the street,” she said. “Everything would be finished. My marriage would be over. I don’t think I’d be here.”