Surprising study finds everyday cleaning products rival cars as big source of air pollution

Research shows paints, perfumes, sprays and other synthetic items contribute to high levels of ‘volatile organic compounds’ in air

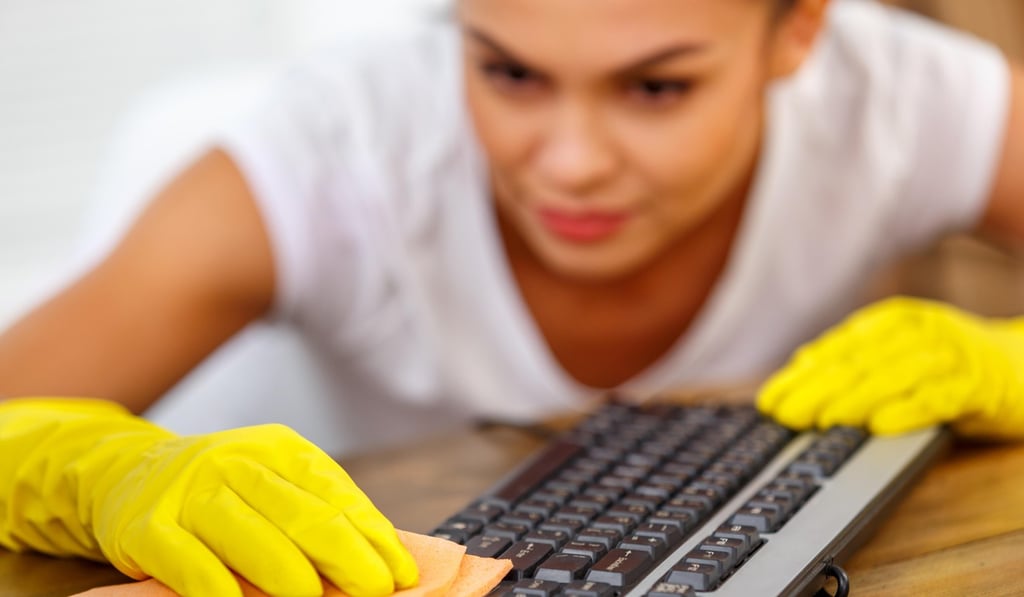

Household cleaners, paints and perfumes have become substantial sources of urban air pollution as strict controls on vehicles have reduced road traffic emissions, scientists say.

Researchers in the US looked at levels of synthetic “volatile organic compounds”, or VOCs, in roadside air in Los Angeles and found that as much came from industrial and household products refined from petroleum as from vehicle exhaust pipes.

The compounds are an important contributor to air pollution because when they waft into the atmosphere, they react with other chemicals to produce harmful ozone or fine particulate matter known as PM2.5. Ground level ozone can trigger breathing problems by making the airways constrict, while fine airborne particles drive heart and lung disease.

In Britain and the rest of Europe, air pollution is more affected by emissions from diesel vehicles than in the US, but independent scientists said the latest work still highlighted an important and poorly understood source of pollution that is currently unregulated.

“This is about all those bottles and containers in your kitchen cabinet below the sink and in the bathroom. It’s things like cleaners, personal products, paints and glues,” said Joost de Gouw, an author on the study at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

“When you think about how much of those products you use in your daily life, it doesn’t compare to how much fuel you put in the car. But for every kilogram of fuel that is burned, only about one gram ends up in the air. For these household and personal products, some compounds evaporate almost completely.”