US judge scraps New York nunchuck ban as it violates ‘right to bear arms’

- American martial arts enthusiast argued the ban on nunchucks in his home stripped him of the right to defend himself and the judge agreed

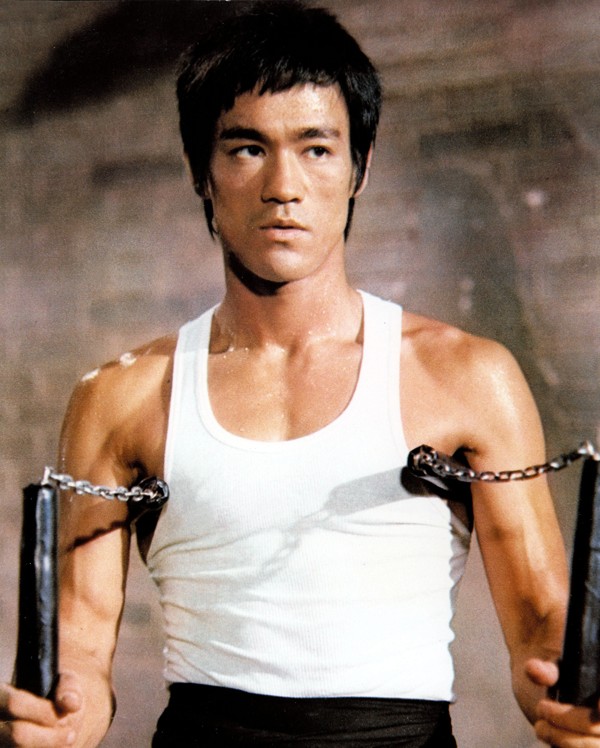

Just blame Bruce Lee. Back in 1974, New York state decided to ban the possession of nunchucks as lawmakers feared they were becoming enticing tools of violence among hooligan children and street criminals who were exposed to the weapons on television. They were so dangerous, lawmakers said, not even karate teachers could keep them in a locker at home.

But while being dangerous might have been a good enough reason then, it is not any more.

US District Judge Pamela Chen on Friday struck down New York’s nunchuck ban as unconstitutional, finding that nunchucks are protected under the Second Amendment right to bear arms.

In her 32-page ruling, Chen concluded that nunchucks are commonly used by law-abiding citizens – karate enthusiasts or for self-defence – so banning them violates the Second Amendment.

While the nunchucks ruling may be an important affirmation of those principles for gun-rights advocates, after nearly 15 years of litigation, the ruling represents a long-sought victory for one New York amateur martial artist.

James Maloney, a lawyer, was arrested for possessing nunchucks at home in 2000. Since 2003, while representing himself, he has argued the law prevented him from teaching his children specialised karate moves he invented, involving nunchucks. He called his style “Shafan Ha Lavan”.

Maloney believed that the government’s ban on nunchucks in the home stripped him of the right to defend himself, which the Supreme Court has said is a central principle of the Second Amendment.

Even though he only asked that Chen recognise his right to at least keep nunchucks at home, the judge went a step further, finding the entire law targeting nunchucks to be unconstitutional.

“The court granted relief somewhat beyond what I had asked for, but I am not about to complain,” Maloney wrote on his blog, where he has been chronicling his one-man nunchuck battle. “Thanks to the many who have helped in many ways along the way. It has been a path with heart.”

The ruling, if left in place, would make Massachusetts the only state to still ban the weapon outright, according to the ruling, though other states restrict their use.

Kung fu was all the rage in 1974, when New York state lawmakers debated adding nunchucks to its list of banned weapons, joining machine guns and brass knuckles. Bruce Lee’s death in 1973 was still fresh and so was his last film, Enter the Dragon, which was released a month after he died and immortalised as one of the best kung fu films. The television series Kung Fu was in full swing, too. The Street Fighter, premiering in 1974, surely horrified lawmakers concerned about nunchucks, as it was the first American film to earn an X-rating purely for violence.

“As a result of the recent popularity of ‘kung fu’ movies and shows,” the New York District Attorney Association wrote in one 1974 letter, “various circles of the state’s youth are using such weapons. The chuka stick (nunchucks) can kill, and is rightly added to the list of weapons prohibited by section 265.00 of the Penal Law.”

Until now, nearly all the state needed to do to uphold its nunchuck ban was prove that it was rationally related to a government interest, such as keeping citizens free from nunchuck attacks.

That’s why, at least initially, Maloney kept losing. He lost in 2009 in the US Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit, when a panel that included future Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor ruled against him on the grounds that New York had showed a rational basis for its nunchuck ban. At that point, the Second Amendment wasn’t being used in reference to state laws, thanks to an archaic 1876 High Court ruling.

When the sticks are swung … it can bust someone’s skull

But that was about to change, as foreshadowed by Sotomayor’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing later that year, where Maloney’s case made a cameo.

Sotomayor’s panel ruling against Maloney cost her the support of the National Rifle Association. At the time, a crucial Second Amendment case, McDonald v. Chicago, was pending through the lower federal courts, and gun-rights advocates believed it could have the potential to overturn that long-ago 1876 Supreme Court ruling standing in their way. McDonald was important to them because a positive ruling could make it harder for state governments to pass restrictive gun laws.

Republicans feared the ruling against Maloney indicated Sotomayor would not be open to overturning the 1876 ruling through McDonald, a case challenging a blanket ban on handgun registrations.

But Sotomayor managed to reassure them – in part by stressing that Maloney’s case was just about nunchucks.

Republican Senator Orrin Hatch began by asking, “Doesn’t your decision in [Maloney v. Cuomo] mean that virtually any state or local weapons ban would be permissible?”

“Sir, in Maloney, we were talking about nunchuck sticks,” she responded, eliciting muffled laughs from the room. She explained to Hatch how nunchucks are used: “When the sticks are swung, which is what you do with them, if there’s anybody near you, you’re going to be seriously injured … it can bust someone’s skull.”

Hatch backed off.

But the concerns raised by Hatch and other Republicans about Sotomayor’s view in Maloney’s case were not misplaced. The next year, in a landmark 2010 decision in the McDonald case, the Supreme Court ruled the Second Amendment applies to state laws, a major victory for gun-rights advocates that has since allowed the NRA to file many more lawsuits challenging gun restrictions.

It was also the ruling that made Maloney’s nunchuck victory possible on Friday, according to Chen’s decision. In light of McDonald, the Supreme Court remanded Maloney’s case back to the lower federal courts in 2010.

Lawyers for the Nassau County District Attorney’s Office, the jurisdiction where Maloney was arrested, tried to argue “the dangerous potential of nunchucks is almost universally recognised”. But Chen didn’t buy it.

Citing the history nunchucks Maloney presented, Chen wrote: “The centuries-old history of nunchaku being used as defensive weapons strongly suggests their possession, like the possession of firearms, is at the core of the Second Amendment.”