Naive tourist? Bumbling spy? Months after her arrest at Mar-a-Lago, Zhang Yujing remains a cipher

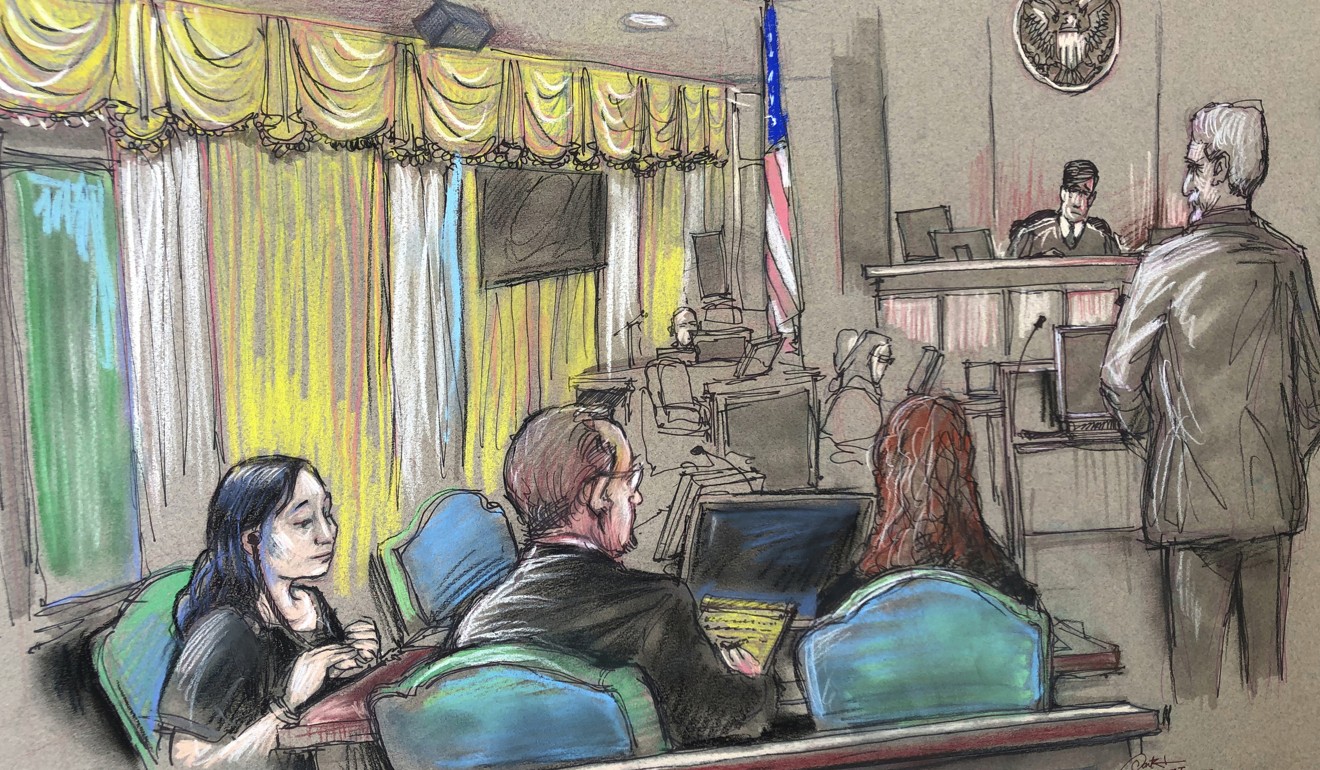

- Zhang, expected to appear next week in federal court on charges that carry up to six years in prison, is representing herself

- The Shanghai native with a financial services background may have been an ‘unwitting asset’ of Chinese intelligence, a former FBI agent says

This story was produced jointly by the South China Morning Post and the Miami Herald, with reporting from China and the US.

When Zhang Yujing, protagonist of the “Mar-a-Lago intruder” case, listed Prison Break among her favourite TV shows on a long-inactive social media account, the prospect that she herself could one day face years behind bars in the US must have seemed unlikely, if not unthinkable.

Back in 2008, fresh out of university, she would take to the Chinese social network Renren to share pictures of exquisite desserts, the poetry of Yeats and humorous posts about the Shanghainese dialect, the vernacular of her hometown.

She was, in the words of a man she later dated in 2013, “just a normal girl”.

Chinese woman charged with illegally entry of Mar-a-Lago

“Ordinary looks, ordinary family, and an ordinary education – everything was ordinary,” said Yao, who was willing only to give his surname due to the sensitive nature of the far from ordinary predicament now entangling Zhang.

In March, Zhang, 33, was arrested after gaining entry into US President Donald Trump’s private club in Florida, Mar-a-Lago. Prosecutors allege that Zhang lied her way past a Secret Service security checkpoint to enter the Palm Beach resort, first telling guards she was there to visit the pool, then saying she was there to attend a charity fundraiser – an event that had been cancelled days earlier.

Zhang is to appear in federal court in Fort Lauderdale next week to defend herself against charges – lying to a federal officer and trespassing – that, should she be found guilty, could spell up to six years in prison, hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines and certain deportation to China upon release.

The Shanghai native has not been charged with espionage, but behind the scenes federal prosecutors have filed classified evidence in her case – indicating the existence of a parallel US investigation into whether she was working as an agent for Chinese intelligence services or had any contact with government officials.

Publicly, prosecutors have also not ruled out bringing more charges against Zhang, while a judge presiding over her bail hearing said it appeared she “was up to something nefarious”.

At the time of her arrest, Zhang was carrying multiple cellphones, a laptop, an external hard-drive and a thumb drive. A later search of her hotel room found more electronic devices and US$7,500 in $100 bills.

The mystery surrounding Zhang has only grown since her arrest, following a series of actions she has taken that have confounded observers. Despite having no previous legal training, she has fired her lawyers – public defenders appointed by the court – and chosen to represent herself.

She has been accused by a judge of “playing games” with the court, after refusing to answer his questions and directly requesting to be freed from jail. And in a further perplexing twist, she has been calling up dozens of businesses in the Palm Beach area asking for financial help and legal advice, according to previously unreported telephone records.

Ahead of her trial next week, the South China Morning Post partnered with the Miami Herald to piece together a picture of Zhang’s life before and after her fateful trip to Florida in March, speaking to acquaintances of Zhang along with people in the United States who have had contact with her. Many interviewees declined to be named.

A career in financial services

Zhang was born in 1986 into a Shanghai that was a hotbed for the economic reforms pushed by China’s then-leader Deng Xiaoping, and her education and career revolved around finance.

After graduating from the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics with an undergraduate degree in economics, finance and financial management in 2008, Zhang joined AIG-Huatai, a joint venture between American Investment Group and China’s Huatai Securities.

Now known as Huatai-Pinebridge (the company was renamed in 2010), the Shanghai-headquartered joint venture describes itself as the largest active quantitative analysis fund manager in China. The firm declined to comment or confirm Zhang’s employment there, but an expired certificate registered under Zhang’s name with the Securities Association of China described her as an employee at Huatai-Pinebridge and her work as “regular securities business”.

She is also identified as having worked there by a paper she published in the Business Culture journal about qualitative and quantitative investment analysis, while a LinkedIn page under her name lists her job title at the firm as “product manager”.

But after Zhang left Huatai-Pinebridge in the early months of 2013, around the time her mother died, scant public information exists about her next steps. Yao, who went on a handful of dates with her in 2013, said he believed she went on to continue working in the field of fund management.

Eleven years her senior, Yao was setting up his own hedge fund at the time, and posted about his line of work frequently on the Chinese microblogging site Weibo, through which Zhang came to know of him.

“The reason she approached me was because she wanted to set up her own company and wished to gain some understanding and find partners,” Yao said, adding that while he was not sure whether she was particularly driven by money, “she was very interested in what car I drove”.

Working for her father

Suggesting she has since been successful in amassing sufficient wealth to live comfortably in one of China’s most expensive cities, she was the owner of her own BMW and had paid of roughly half the mortgage on her 9 million-yuan (US$1.26 million) Shanghai home before her travel to the US in March, according to sworn testimony she gave in April.

Recent years saw her travel to the US multiple times on a 10-year visa, including a December 2017 trip to visit tech companies in Silicon Valley and Boston organised by a Beijing-based company offering overseas business tours for Chinese executives and investors.

Before her arrest, Zhang was also working as a consultant for an asset management company in Shanghai, she told the court. She was paid “per project”, she said, though had not received any income in 2019.

Filings with the Shanghai municipal government’s enterprise credit information database indicate that the company – Zhirong Asset Management – is owned by Zhang Xuefeng, who, a source familiar with the case confirmed, is Zhang Yujing’s father.

Beyond its wide variety of asset management and financial consultation services, Zhirong’s website also touts a “VIP club”, advertising access to events like the Oscars and promising photo opportunities with “international celebrities”.

A recent visit to the company’s registered address in Shanghai led to a residential property out in the city’s southeastern suburbs. There was no firm operating from the residence, according to a local security guard.

Multiple emails to Zhirong went unanswered, while a call to a number listed in company records was answered by a man who said that Zhang Xuefeng was a friend of his and was unable to take calls.

An unwitting operative?

Zhirong’s “VIP club” service resonates with a growing industry in China aimed at offering wealthy clients access to influential political figures overseas. Indeed, the charity gala that Zhang told Mar-a-Lago staff she expected to attend was to feature a guest appearance by President Trump’s sister, Elizabeth Trump Grau.

Zhang was drawn to the Trump family because of its connections to the real estate world, according to two sources familiar with the investigation, and had told the man who peddled the March event to her that she was interested in real estate opportunities in New York and Miami.

The event promoter – Charles Lee, who ran organisations co-opting the United Nations’ name – had previously offered Zhang a tour package to meet Bill and Hillary Clinton, but she declined because, these people said, she was not interested in former presidents.

Who is Charles Lee? Chinese businessman has a chequered past

Zhang, they said, was under the impression she would be able to meet Ivanka Trump at Mar-a-Lago – though the president’s daughter was not listed among the event’s guest appearances – and believed her trip there would help her achieve her goal of making millions of dollars.

The doors to that dream were shut firmly when the event was cancelled days before Zhang’s arrival, following media scrutiny over another one of its promoters, Cindy Yang, the Chinese-American former day spa owner who ran a business offering Chinese clients access to American political elite.

Federal prosecutors said they have proof Zhang was informed of the event’s cancellation before her flight to the US on March 28. And while her public defenders had argued she may not have been able to communicate effectively with staff at Mar-a-Lago due to a language barrier, she has spoken in fluent English during subsequent hearings. Combined with the trove of electronic devices she had when Secret Service agents detained her, these factors have fuelled suspicion of a nefarious agenda.

Cindy Yang speaks out to decry ‘unfair’ treatment

Federal investigators would be looking “at the affiliation of her father’s company, and the companies that she’s affiliated with or the people to see if they have ties to the intelligence services,” said Robert Anderson, a 20-year Federal Bureau of Investigation veteran who served as the FBI’s assistant director of counter-intelligence.

Anderson, now chief executive of Texas-based Cyber Defense Labs, said it was also plausible that Zhang had been tacitly encouraged to test the level of security surrounding Mar-a-Lago without necessarily knowing she was being tasked to do so at the behest of Chinese intelligence.

“There are witting assets, and then there are unwitting assets,” he said, citing China’s intelligence community’s history of using “expendable” laypeople for scouting operations so as not to sacrifice highly skilled operatives. “This woman may or may not have even known that what she was doing was actually being monitored or manipulated by the Chinese government.”

Anderson said it was “absolutely” possible that she had been pressured to fire her defence lawyers – as she did in June, against the advice of the judge – in an attempt to weaken her case and increase the likelihood of a swift jail sentence.

If Zhang, who told the judge she made the decision of her own volition, was being used by Chinese intelligence officials, Anderson said, “they absolutely could [not] care less if this woman spent two years or 10 years in a federal prison in the United States – especially if it’s a way of distancing themselves from that person.”

When reached in August, the man who answered the phone number connected to Zhang Xuefeng said that Zhang Yujing had dismissed her lawyers because she wanted minimal exposure and believed that lawyers tended to speak to the media about the case.

The Chinese consulate-general in Houston, Texas, which oversees consular affairs in Florida, did not respond to requests for comment about the nature of its communications with Zhang, though a staffer reached at the number Zhang called multiple times acknowledged speaking with her in April and July.

The staffer, whose number was listed in Zhang’s phone call log during her time at the Palm Beach Belle Glade detention centre – one of several she has been held at since her arrest – said only that he had called her “because she is a Chinese citizen.

“I would like to know what happened recently.”

Desperately seeking support

Zhang’s calls from detention were not limited to the consulate, however. Belle Glade records show she made 280 calls – 58 of which went through – from the time of her arrest to August 15.

Many of those calls were to businesses, including real estate agents, bond brokers, a home care provider and a trucking company. In one call to a real estate investor, Zhang tried to persuade him they knew each other and asked for money.

“She kept asking me questions,” said Clayton Davis, who has business interests in Palm Beach. “First of all, I couldn’t understand half of what she was saying. She kept saying she needed money.”

“I thought it was weird,” said Davis, who ended up blocking the number.

In another call to a bond agent on July 11 – months after she had already been denied bail and weeks after she had been granted permission to represent herself – Zhang seemed not to grasp the legal procedures her case entailed.

Mar-a-Lago intruder ‘playing games with the court’, US judge says

“I said ‘I can’t help you because your stuff is federal,’” bond broker Francine Adderley recalled. “She was asking me, ‘What’s next? What happens next?’ as if she didn’t know.”

Anderson said that those attempts to get support from strangers could be a sign that Chinese intelligence services had pressured those in Zhang’s personal network not to provide assistance to her.

“If they told her family and everybody else to not help her, she may be at this point just absolutely struggling on her own trying to figure out how she gets out of here,” he said.

As Zhang’s trial approaches, the Chinese government and state media apparatus have remained notably quiet.

Chinese state tabloid says Zhang Yujing was just ‘naive’

Commentary on her case has been limited to perfunctory remarks by the Chinese Foreign Ministry in April confirming that Zhang was receiving consular support, and an April article in Global Times, a state media tabloid, playing down suspicions she was a spy and portraying her instead as merely a “naive” victim of a scam.

Yao, the man Zhang dated briefly in 2013, agreed – albeit in blunter terms.

“Spies are very professional,” he said. “There are no spies that are this stupid.”

Sarah Blaskey reports for the Miami Herald, where Jay Weaver and Nicholas Nehamas also contributed reporting. The Post's Owen Churchill and Meng Jing reported from Washington, and Daniel Ren reported from Shanghai.