In limbo: thousands of Chinese citizens stuck in US illegally, and Beijing won’t take them back

- One immigrant spent time in prison and was ordered deported but instead was later pardoned and is now a US citizen

- China’s failure to cooperate in the process has earned it a ‘recalcitrant’ label from the US Department of Homeland Security, but there is little recourse

Xiaofei “Eddy” Zheng moved from Guangzhou to California at the age of 12, fell in with Asian gangs and was convicted of armed robbery and kidnapping at 16. Finally emerging from San Quentin prison in 2005, some 19 years later, the US ordered him deported back to China. All that was required was Beijing’s sign-off and he would be gone.

For most countries, that would be routine. But the embassy refused to cooperate, claiming there was no proof Zheng was Chinese, leaving him in limbo for years.

“It was just constant fear every day. I couldn’t plan anything. I couldn’t set goals,” said Zheng, who would battle bureaucrats and deportation orders for another dozen years before gaining US citizenship in 2017. “The Chinese, it does accept people, but it’s just very selective.”

Atop the long list of US-China problems, add one more: the thousands of Chinese citizens illegally in the US that Beijing refuses to take back.

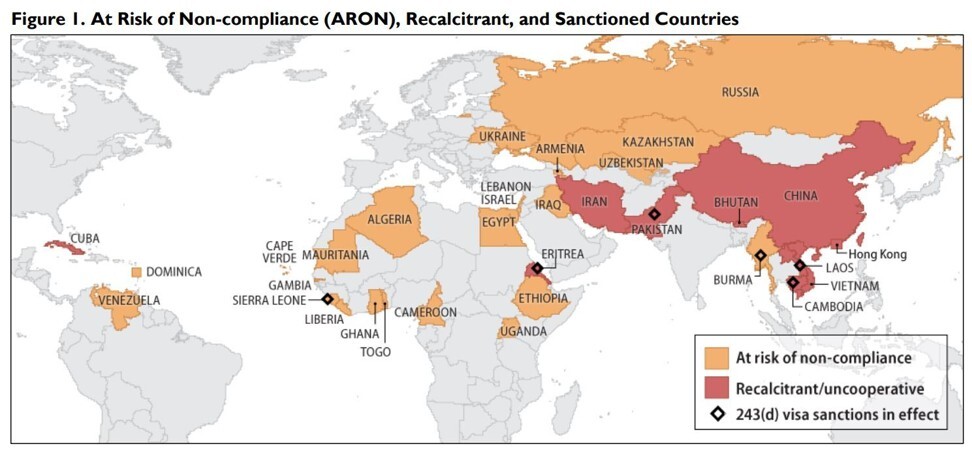

China’s failure to cooperate has seen it labelled “recalcitrant” by the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS); it is one of some dozen such countries and special regions, including Eritrea, Iran, Pakistan and Cuba.

“China is obviously the biggest offender,” said Thomas Kellogg, executive director of Georgetown University’s Centre for Asian Law. “If there’s no cost in not taking them back, and the only cost is that the US keeps asking, so what?”

As much as Washington might like to, it cannot simply pile them into a plane and head for Beijing.

Under international rules, recipient countries need to approve those arriving, even their own citizens. Airlines will not let passengers board without proper documentation. And China often claims – sometimes justifiably – that documents are insufficient, passports counterfeit and those involved aren’t Chinese.

Chinese man fights to stay in US after judge blocks deportation mid-flight

Some have committed serious crimes. Zheng and two accomplices were convicted of holding up a wealthy Chinese-American family at gunpoint in July 1986, stealing US$34,000 in cash and goods.

Most, however, are ensnared in the US immigration maze for minor infractions like overstaying visas or breaking traffic rules.

For years, the issue was a relatively modest irritant between the two countries. After his election on an anti-immigrant platform, however, US President Donald Trump increased pressure on “recalcitrant” nations to repatriate their citizens.

Last month, in its latest attempt, the White House called out China in a key strategy report, accusing it of breaking its commitments and “creating security risks for American communities”.

China, however, has little incentive to cooperate, especially amid a massive trade war and US accusations it caused hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide by hiding Covid 19’s early spread, charges Beijing denies.

“When China is motivated to keep good relations with the US, they have been willing to do a bit more,” said a former senior State Department official. “That is not the situation now, obviously.”

Beyond that, analysts said, Beijing sees little upside in welcoming back criminals and rule breakers. “These are a bunch of people who, from their perspective, are not the best and brightest,” Kellogg said.

Other impediments include the lack of an extradition treaty or much history of cooperating on immigration issues – coloured by a reluctance to deliver suspects into an opaque system with limited rule of law – and an overhaul of China’s immigration agency in March 2018, analysts add.

How Trump is using coronavirus crisis to push his own agenda

“China can be very difficult,” said Matthew Kolken, a partner with the Kolken & Kolken law firm. “They have a lot of people and don’t really care about these few thousands.”

Beijing tends to want to pick and choose those it takes back – human rights activists or victims of religious persecution, for instance – rather than a wholesale acceptance, experts said. Beijing’s wish list includes corrupt Chinese officials or white collar criminals with ill-gotten gains targeted under its “Fox Hunt” and “Skynet” campaigns.

But the US is reluctant to comply, said a knowledgeable federal official, since this undercuts US leverage and could encourage selective justice.

Washington also shares blame given its labyrinthine immigration system, said others. “The US expects other countries to make great efforts and to expend considerable resources to correct for our inept system,” the former senior diplomat said.

The Chinese embassy in Washington did not respond to a request for comment. In the past, Chinese officials have accused Washington of hypocrisy for touting legal principles while refusing to hand over suspects that Beijing wants.

US options against “recalcitrant” countries include: issuing diplomatic complaints, raising the issue in meetings, threatening to withhold aid and, under a 1952 immigration provision, blocking all tourist, business and other visas until the country complies, the only one with real teeth.

In 2001, Washington used such tactics successfully after Guyana refused to accept 113 of its citizens whom the US considered dangerous. Within two months of denying visas to government officials and their families, Guyana accepted 112 of them back.

The Trump administration has stepped up visa sanctions against Cambodia, Eritrea, Guinea and Sierra Leone with varied success. And, late last week, it added Burundi to that list.

Revealed: the team behind China's Operation Fox Hunt against graft suspects hiding abroad

But China is no Burundi, making blanket visa threats far more consequential given its clout, integral ties with the US, and ability to retaliate. “Most countries don’t hold paper for trillions of dollars worth of US debt,” said Kolken. “Good luck even buying a freaking microwave that doesn’t have ‘Made in China’ stamped on it. We have no leverage.”

That has not stopped the administration from trying. Trump’s first executive order as president directed US officials to use all available means against “recalcitrant” countries, and analysts said Trump was not above using draconian visa sanctions given his confrontational approach and willingness to defy expert advice.

“Is it practical to do that? Probably not. Is it a smart thing? Probably not. But he’s capable of doing it,” said Kolken. “I wouldn’t put anything past Trump.”

If there’s no cost in not taking them back, and the only cost is that the US keeps asking, so what?

Less drastic would be a sharp reduction or end to 10-year tourist and business visas, said Gary Chodorow, a Beijing-based immigration lawyer.

The State Department said it did not comment on the specifics of diplomatic conversations. “We continue to raise this as an issue of concern in our bilateral dialogue,” a spokesman said.

Estimates of the number of Chinese stranded in the US by the impasse range from hundreds to tens of thousands. In 2015, US immigration authorities said around 38,000 Chinese were awaiting deportation, including 900 classified as violent offenders.

Others suggest those figures are inflated, adding that even DHS may lack accurate numbers. “It’s hard to make an exhausting accounting,” the federal official said. “We don’t really know and just want them the hell out of here.”

DHS did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

US immigration policy could help China win technology race

The cases clog an already overloaded US immigration system with hearings, appeals and incarceration dragging on for years before final removal orders are issued. But US law does not permit DHS to detain deportees indefinitely if a “recalcitrant” country will not accept them.

“The government has no choice but to release you,” said Alex Nowrasteh, the Cato Institute’s immigration studies director.

That has seen large numbers of Chinese, and other nationals, released into US society, unable to work legally and subject to deportation at any time depending on Beijing’s mood.

The US should consider tougher visa and other sanctions against “recalcitrant” countries given thousands of criminal immigrants, “some with serious criminal records, being released into the interior of the United States”, Senator Chuck Grassley, a Republican from Iowa, said last week.

The stalemate has a human cost as well. That is something Zheng knows first hand, having spent decades in limbo, often straddling worlds, until he turned his life around in spectacular fashion.

He landed in Oakland in 1980, with his People’s Liberation Army officer father, accountant mother and two older siblings. He was unable to speak English or understand the culture. After a comfortable life in Guangzhou, their move into his grandparents’ small apartment was jarring.

“The three of us slept on this sofa bed,” he said. “This was not like the comfortable space or the American dream that was painted to us.”

Money was tight. His father worked long hours at Burger King and his mother was a live-in housekeeper. Without supervision, Zheng started skipping school, stole car stereos, shoplifted clothing from Macy’s and guarded a bordello with a shotgun.

Chinese fugitive returns from US as Skynet corruption crackdown continues

In a fateful decision, he joined two other delinquents in robbing a family in San Francisco’s Chinatown and was caught after forgetting to turn on the getaway car’s headlights. He received a life sentence, becoming the then-youngest prisoner in San Quentin.

Over the next two decades behind bars, he learned English, read avidly, wrote poetry and got high school and associate college degrees. At one point he petitioned prison authorities to provide Asian culture classes, earning him 11 months in solitary confinement.

That contested punishment and his growing reputation as a mediator adept at bridging racial divides and defusing violence caught the attention of Asian-American and other community groups outside the walls.

“I was able to learn how to be patient,” Zheng said. “Either you let the time do you or you do the time.”

Released after a dozen parole attempts, he was immediately detained by immigration authorities, ultimately losing his fight against deportation despite widespread community support.

After 23 months, US authorities could no longer legally hold him but pushed him to assist in his own deportation.

“Why should I cooperate with you to deport myself? But they said, ‘if you don’t do what we ask you to do, we’ll put you back in custody’,” Zheng said. “They kept forcing me to go to the Chinese embassy to get documents.”

Embassy officials, for their part, questioned whether he was Chinese, he added. “They just didn’t bother.”

He continued expanding his community ties, worked as a counsellor for troubled youth, spoke in schools and prisons, ultimately winning the support of state senators, judges and prosecutors.

In 2015, he received a pardon from the governor and, two years later, was granted US citizenship. That same year, he founded New Breath Foundation to help immigrants and those affected by incarceration, violence and deportation.

Particularly gratifying was reconciling with his victims, a scene played out in Breathin’: The Eddy Zheng Story, a documentary about his life released in 2018. “How do I repair the harm that I have caused?” he said. “I was very grateful. She accepted my apology and forgave me.”

Zheng said the US-China impasse and broader immigration system have left untold numbers hanging.

“They want to disrupt their lives, separate their families, send them to a country they haven’t been to forever,” he said. “It’s traumatic.”

Illustration: Lau Ka-kuen