Northern exposure: Alaskans hope hosting US-China talks helps rebuild state’s ties to Beijing

- In the wake of the Anchorage summit, state officials believe the time is right to thaw out trade and tourism links with the world’s second-largest economy

- US wariness of Chinese investment has deepened amid national security concerns, but many Alaskans would welcome Chinese buy-in, especially for a long-sought natural gas pipeline

After hosting the first encounter between the new Biden administration and its Beijing counterparts in a session marked by acrimony, Alaska still hopes its new-found notoriety will spur profitable ties with China.

“I am optimistic that publicity from meetings like this will put Alaska on people’s minds as a vacation destination – and as a trading partner,” said Lise Falskow, chief executive of the Alaska World Affairs Council.

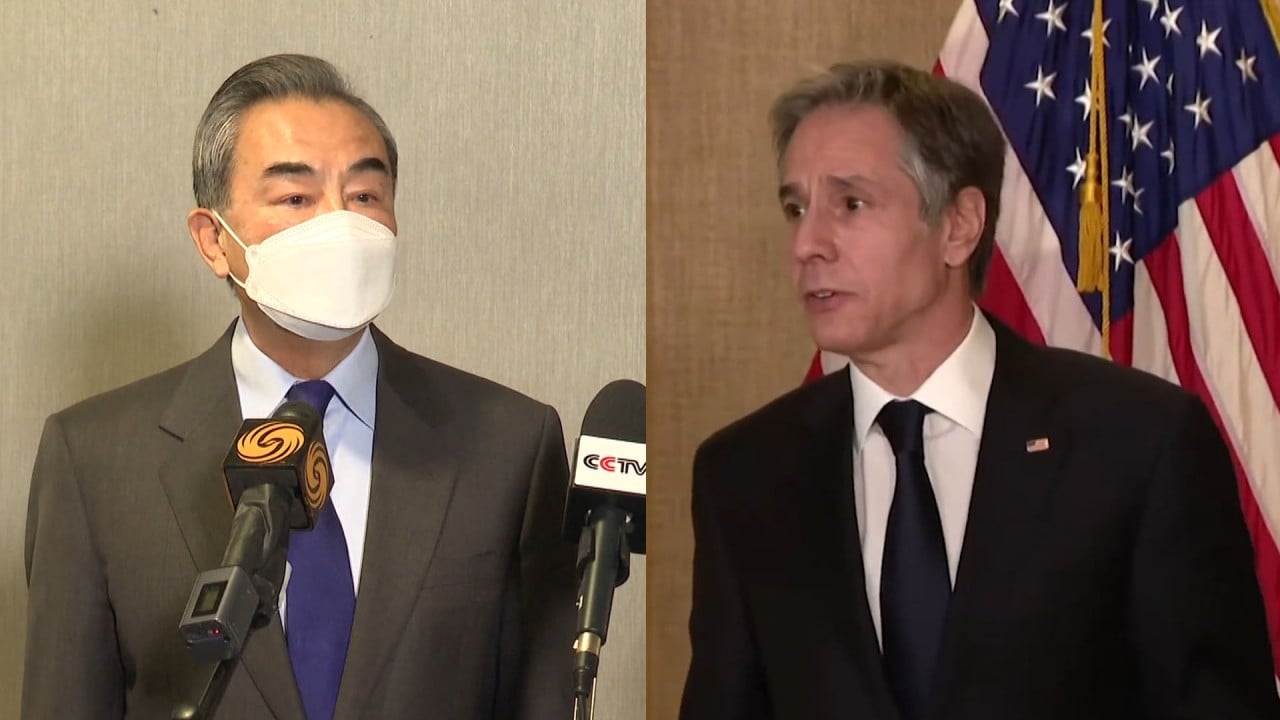

Last month, a seemingly routine meeting between US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and top Chinese diplomat Yang Jiechi in America’s coldest state unexpectedly heated up when diplomats dropped their scripts and turned decidedly undiplomatic.

As the sit-down started, the two sides traded bitter accusations over human rights, rude American hosting, arrogance and missed dinners. Accounts of the dust-up quickly spread across the internet and across the Pacific, generating memes, transforming Chinese envoys into national heroes and all but ensuring that the world’s two largest economies will not achieve rapprochement any time soon.

Alaska is in many ways an ideal partner. This resource-rich state produces commodities that China needs to feed its massive economy. And its scarce population and labour force – Alaska has fewer people than a single district in Beijing – leave it less concerned than other American states about exporting factory jobs.

That helped China become Alaska’s largest export market by 2011, surpassing Japan as the state’s top destination, led by seafood, minerals, forestry products and energy. The state’s shipments to China were worth US$1 billion in 2018, dropping to US$855 million in 2019 before rebounding to US$1.1 billion in 2020.

Alaska has also seen tourism from China grow steadily, helped by a hard-to-kill myth that conceiving a child under the Northern Lights produces fortune-blessed, high-IQ babies.

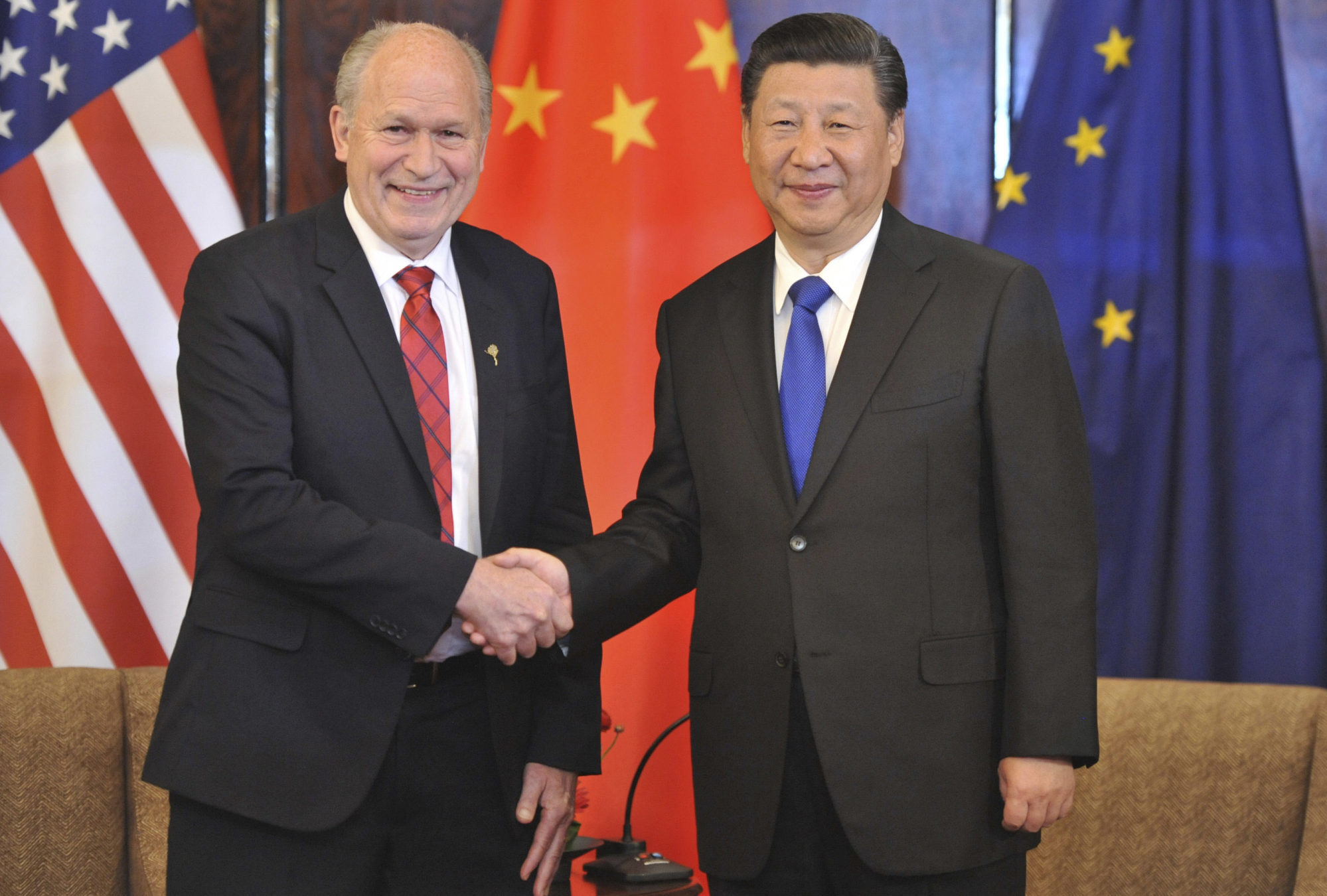

During a 2017 visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping and China’s first lady, Peng Liyuan – early in Donald Trump’s administration when ties seemed promising – wine glasses clinked and “win-win” language flowed freely. Bill Walker, then Alaska’s governor, met Xi in the same conference room at the Captain Cook Hotel where last month’s Yang-Blinken row occurred.

“And we had a nice meal upstairs,” said Walker, recalling better times in his office decorated with ceremonial shovels and photos of himself with Trump and former president Barack Obama. “We fed them that time.”

But the state’s population of just 735,000 and far-off location also give it limited political clout with Washington when strong global winds rage.

Seafood, Alaska’s largest export, got slammed with high tariffs a few months after Xi’s visit when the US-China trade war turned nasty. By 2020, those sales to China had fallen nearly in half – even as Trump made sure politically weighty Midwestern states received billions of dollars in relief.

“Seafood gets caught in the fray,” Jeremy Woodrow, executive director of the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute, said. “We’re always the victim of larger battles.”

Still, should rough transpacific seas eventually settle down, Woodrow has high hopes for China’s burgeoning middle class and the promising market they offer for lobster, crab, salmon and niche products like sea cucumbers, sea urchin and geoduck. In the meantime, Alaska has turned to Southeast Asia to help fill the gap.

Other Alaskan industries have barely noticed the US-China tariff chest thumping.

It’s a little after noon at Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport as manager Jim Szczesniak surveyed cargo jets just arriving from Asia.

Helped by the pandemic and its ideal location for refuelling heavily laden US-Asian jets, Anchorage has secured its position as the world’s sixth-largest cargo airport. Domestic and international cargo growth is “on fire”, Szczesniak said, up 16 per cent in 2020, part of a projected 3.4 per cent annual growth in North America-East Asia traffic through 2039.

Most Chinese cargo is currently routed through Hong Kong International Airport, although Szczesniak expects more direct flights to Anchorage from second-tier Chinese cities as traffic grows and China expands its cargo aircraft fleet.

“We can catch a fresh king salmon in Alaska and have it in Hong Kong in 24 hours,” he said. “If it goes to North America, they fillet it. If it goes to Asia, they keep the head on.”

Facing fewer constraints than its rivals in bigger American cities – Anchorage has ample land to expand onto and fewer neighbouring residents complaining about noise – the airport has a fourth runway on the drawing board and US$1 billion in planned private investment for cargo sorting, transfer, cold storage and repair facilities.

Passenger traffic is a different story, however. Downstairs in the empty international passenger terminal, a janitor trundled past the empty check-in counters of Russian and South Korean airlines near a yellowing stuffed bear exhibit.

In the late 1980s, these halls were crammed with travellers stretching their legs and spurring duty-free sales that once reportedly rivalled Hong Kong’s. But after Russia started permitting overflights and passenger aircraft extended their range – people weigh less than cargo, enabling jets to travel further – Anchorage watched its international passenger traffic fly away.

Still, the airport hopes to lure some of it back by attracting “long, thin” passenger routes still in need of refuelling, including Los Angeles-East Asia and Latin America-East Asia links.

Alaska also hopes to boost the number of Chinese tourists, who now number around 10,000 annually, building on Xi’s surprise stopover in Anchorage after his 2017 meeting with Trump at his Mar-a-Lago resort.

“Chinese consumers started asking, where is Alaska?” said Greg Wolf, executive director of World Trade Centre Alaska and Alaska’s former international trade director, adding that the state was busy translating menus and lining up bilingual guides.

“And it certainly doesn’t hurt that they had the [latest] meeting here,” he added. “I think people in China are much more aware of us than they were.”

That they certainly are. Still unclear is whether that awareness helps or hurts the state over time.

While some surveys suggest that Alaskans welcome Chinese products, tourists and investment, the state has hardly been immune from the political winds sweeping the US. A Beijing-financed Confucius Institute founded in 2006 at the University of Alaska, Anchorage, shut down last year – ostensibly over “budget pressures”.

“It was framed as a cost-cutting move, but it’s really very difficult to have a Chinese institution on your campus these days,” Paul Dunscomb, a history professor and an East Asia expert who helped set up the programme, said.

Initially, having the institute – an instrument of soft power – on campus was welcomed, Dunscomb said. He recalled making three arguments at the time: learning another language is good; even if you want to remonstrate Chinese officials, doing so in their language is better; and wouldn’t you rather have Beijing spend money on cultural exchanges than weapons.

Eventually, however, as China became more assertive in the South China Sea and its grip tightened over Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Tibet, the programme became less defensible. “I’m very happy to be the former director,” Dunscomb said. “China has decided to forget the soft power, let’s go hard.”

Anchorage and Alaska established sister-city and sister – state relations with Harbin and Heilongjiang province in the mid-1980s, touting their shared far-northern locales. Contact was suspended after the bloody 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, but Xi’s visit helped revive ties, spurring reciprocal trade delegation visits before US-China tensions deepened and enthusiasm waned again.

“I can’t think of much going on with the Heilongjiang state relationship, and that probably says something,” Dunscomb said.

US wariness of Chinese investment has deepened significantly amid concerns over national security and geopolitical angling, but many Alaskans would welcome Chinese buy-in, especially involving a long-sought natural gas pipeline.

“We see the next phase of the evolution of the relationship where China comes here as an investor with their checkbook,” Wolf, of the trade centre, said, even as he acknowledged Washington’s darkening mood: “I think that’s more prevalent in technology, high tech, more of a problem there. I’d like them to have a reset, a restart.”

The Alaskan economy, long dependent on energy, minerals and federal government largesse and now battered by low oil prices and the pandemic’s cruise industry shutdown, is keen for a saviour. It’s also been plagued by the “resource curse”, some say – a tendency to pin hopes on massive, long-shot projects rather than innovation and education.

“It shares many things with a colonial economy,” said Dunscomb. “It’s been eminently clear to anyone with a pulse that we’re no longer a petro state. Why can’t we move on?

“But even suggesting that is akin to heresy.”

Local boosters speak longingly of past crises that melted away concerns of high project costs and environmental degradation, including the global oil shock in 1973 that inspired the US$8 billion trans-Alaskan oil pipeline.

Walker, the former governor, recounted Alaska’s four decades of meetings and lobbying aimed at building a US$38.7 billion natural gas pipeline from the North Slope to serve Asian markets.

He laughed when likened to Don Quixote tilting at windmills. The pipeline led to his decision to run for governor in 2014 and, he insisted, it might have come about if he had not lost his re-election bid in 2018: “My passion was the gas line. I don’t let it go because the gas is still there, the market is still there.”

He got as far as gaining Trump’s support, securing permits, sharing a meal with Xi at the Great Hall of the People and signing contracts in Beijing with prospective gas buyers.

“Things were going pretty good till things didn’t, with all the trade issues,” he said. “I didn’t get a second term and the contracts were cancelled.”

The Chinese are understandably wary. In 2005, the state-owned China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s seemingly winning bid for the California-based Unocal imploded when political tensions allowed Chevron to swoop in.

Walker, though, said he did not see Washington’s growing anti-China mood as a deal breaker – provided Beijing’s stake in the North Slope pipeline remained below 24 per cent or it took no equity stake and was solely a customer.

And despite the Biden administration’s push for carbon-neutral emissions as part of its climate change policies, natural gas was a “bridge” fuel until other sources were more economical, he said.

That has left some Alaskans looking west across the Pacific as well as south to the Lower 48. According to some theories, the Northern Lights inspired early Chinese dragon legends.

“The belief is that the lights were viewed as a celestial battle between good and evil dragons who breathed fire across the firmament,” according to the Aurora Zone website.

These days, many Alaskans are pinning their hopes on the good dragon’s return.