‘I’m a crazy granny’ - artist and activist Evelyna Liang Kan brings creative projects to people in need

- Evelyna Liang Kan escaped communist China as a child and attributes her ‘free spirit’ to growing up on Cheung Chau

- The founder of Art In Hospital has helped refugee children and patients, and even Sai Kung fishermen

Hong Kong bound: I was born in Guangzhou in 1949. When I was just a few weeks old, my parents decided to escape to Hong Kong. My father used to work with a company affiliated to the Kuomintang, so they felt it was better to leave communist China.

We escaped by boat from Guangzhou. My brothers told me the boat was fired on by the army trying to stop people leaving. In the chaos, my five-year-old sister was pushed down and trampled, breaking three of her ribs. A missionary doctor from New Zealand helped to treat her.

My eldest brother was nine years old and remembered the doctor’s name. Later, he emigrated to New Zealand and found the doctor, who remembered my sister.

I had two older brothers and one older sister, a younger sister came later. My father, Dr Chi Chi Liang, taught at the medical school at the University of Hong Kong. My mother was the head matron for the outpatient department at the Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital.

Salted fish: We moved to Sai Ying Pun. No lift, no telephone, no television. I always played on the back stairs and walked down to where they sold salted fish. I love the smell. My grandmother would have that every day – small baby salted fish with rice. She would always share her meals with me. So even now when I walk there and smell the salted fish, I think, “Yes, this is love.”

I attended Ying Wa Girls’ School and then St Stephen’s Girls’ College. I’m dyslexic, so I’ve always used images to help me memorise Chinese characters and English writing. I did theatre, singing, dancing. I expressed myself in every way apart from writing.

Oh Canada: At the age of 17, I went to Vancouver with my parents. A teacher there saw how I struggled with writing essays, so got me writing poetry and prose instead. I was no longer afraid of writing. I started at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and my father thought I should go to medical school, like him. So I got into the pre-med programme.

I lived in a student dormitory and every day I passed the fine arts department. Instead of going to classes for chemistry, anthropology, blah blah, I went into the studios and sat there. A teacher asked me to pick up a brush. He told me to slow down my painting and listen to Japanese koto music as I painted. He taught me how to paint with my heart.

Another professor told me to learn about my Chinese heritage. So I researched the history of China, but also recent events. I became an activist and organised rallies – anti-nuclear war, women’s rights, that Cantonese should be an official language of Hong Kong, not just English. I graduated with a fine arts degree in 1972.

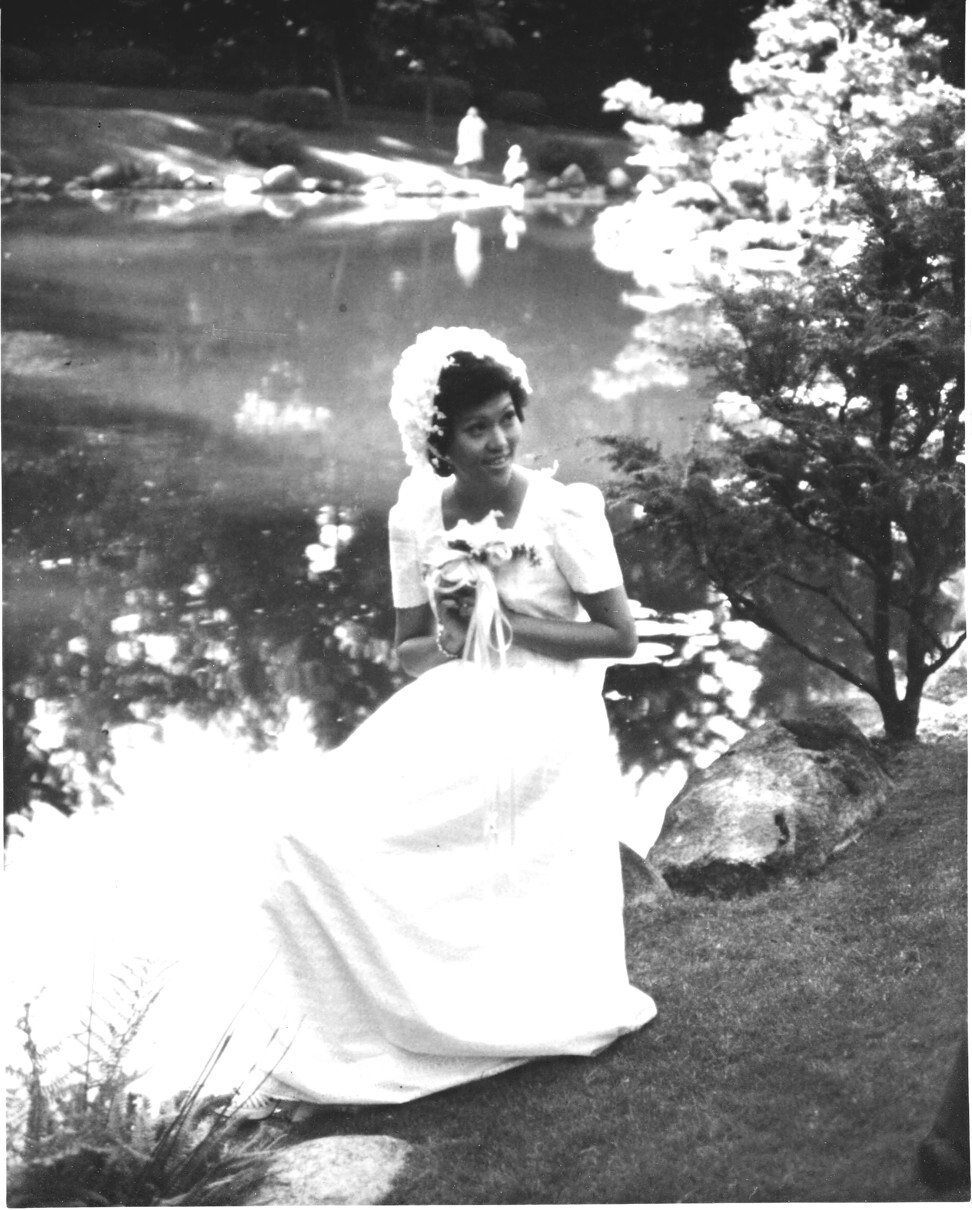

Stand by me: I met my future husband, Frederick Kan Siu-cheong, when I was 16 at a Christmas party in Hong Kong. Then nothing. I went to UBC and a year later, because of the Cultural Revolution, his family also decided to move away from Hong Kong and settled in Canada. At first I rejected him because he wasn’t wild enough, was too stable, but he was always there waiting for me.

With my character, I would want someone wild and crazy, but no, my husband’s not, he’s always there, he’s home. He’s a businessman so he supports my projects when I’m in need of money. He’s a good man. We have two sons. Jonathan, 43, works in Beijing and is a design architect, and Joey, 38, works with an animation design company and he’s also a breakdancer.

Then we asked if we could have a little bit of land. That was at Pillar Point camp, in Tuen Mun. We planted grass and flowers, and it became a healing process for the children. A few years ago, one of the children, as an adult, gave me a big cloth painting. It’s on the wall of my studio. It’s of flowers, and he said, “This is for you.” I was so moved.

My next exhibition is about artworks created by Vietnamese refugees while they were in the camps waiting for their new life. That will be displayed at the Chinese University library from the end of September.

Community artist: In the 1990s, I took the idea of Art in the Camp and made it Art in Hospital, which still exists – colourful murals on hospital walls, particularly in children’s wards, and patients doing their own art. Then a decade ago, a Beijing NGO contacted me, saying the children of migrant workers had no art facilities. So I went up to Beijing twice a year for several years, training artists how to work with these children.

So beginning with fish netting, I created a fashion show of clothes with nets and decoration on the clothes. We used their songs, their stories. They were so proud. I paired them up with a primary school in Sai Kung where they talk with the children about fishing and living in small fishing boats. “How did you cook on board?” the children ask them. “Where was your toilet?” My husband says I do too much. I’m a crazy granny.