The streets of Hong Kong were his canvas: the legacy of ‘King of Kowloon’ – graffiti artist and urban poet

- Most of Tsang Tsou-choi’s protest calligraphy has been erased from the public spaces that were once his billboards, but his work lives on, some in museums

- Had he still been alive, the eccentric artist would surely have had something to say, in his simple brush strokes, about the recent protests in Hong Kong

Tsang Tsou-choi was an eccentric, one-man protest movement and Hong Kong’s original graffiti artist. Dubbed the “King of Kowloon”, Tsang died in July 2007 aged 85, and while much of his protest calligraphy has been erased from the public spaces that were his canvas, he has inspired a new generation.

“Like a lot of people in Hong Kong, I found myself really motivated by Tsang’s graffiti,” says Alex Croft, a 31-year-old artist best known for his mural of Hong Kong residential blocks outside the G.O.D. lifestyle store in the city’s Central district, which became a social-media selfie phenomenon.

“He was so prolific and so dedicated. Rather than painting just random stuff, he was creating a narrative, and I found the backstory – that he imagined himself to be the king of Kowloon – very moving. Above all, I think most of the graffiti artists in Hong Kong who have followed in his footsteps would admire the fact that he did his own thing, no matter what other people thought,” adds Croft, who is based in Sai Kung in Hong Kong’s New Territories.

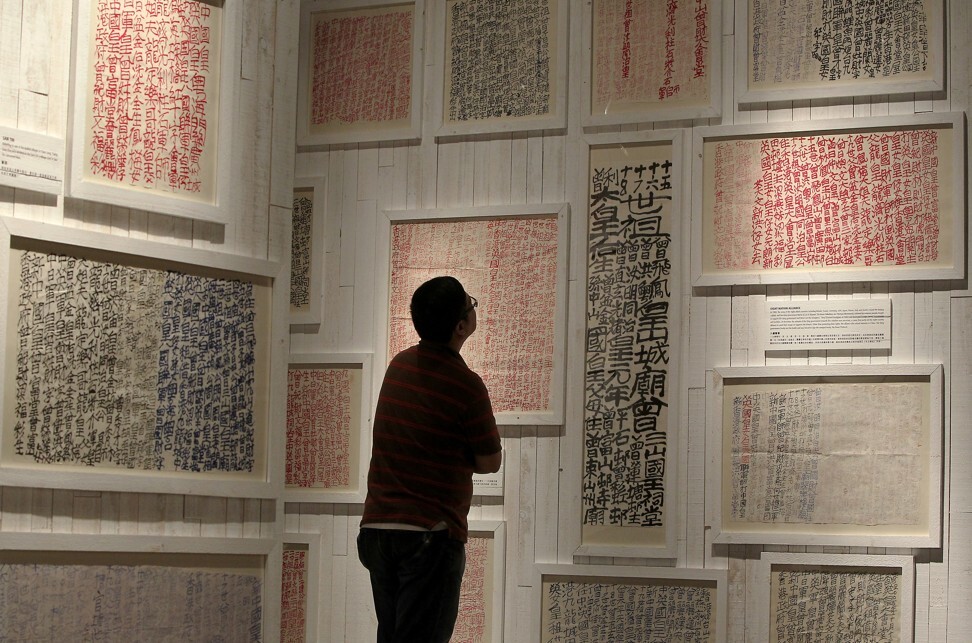

Although Tsang emerged from the margins of society, he was taken up by the art world. Today, his works feature in the collections of Hong Kong’s M+ museum of visual culture and museums and art galleries around the world. Before that happened, he endured many years of near obscurity.

Had he lived, Tsang would be 99 years old today. Born into an impoverished family in southern China’s Guangdong province, at the age of 16 he moved to Hong Kong.

He did not start to paint his graffiti until the mid-1950s, when the city was awash with refugees who had started to pour in from mainland China.

King of Kowloon’s graffiti to appear in new M+ museum

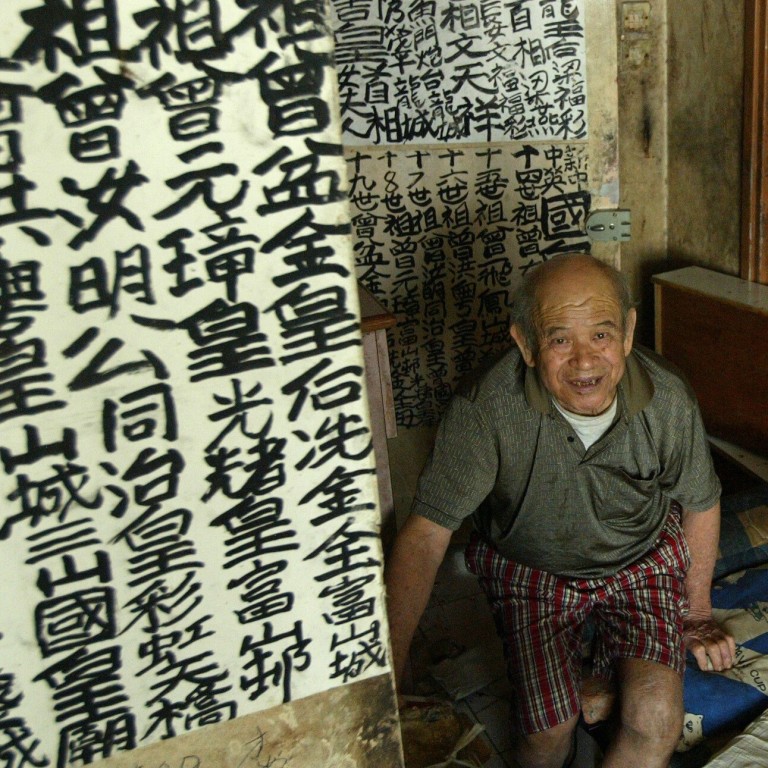

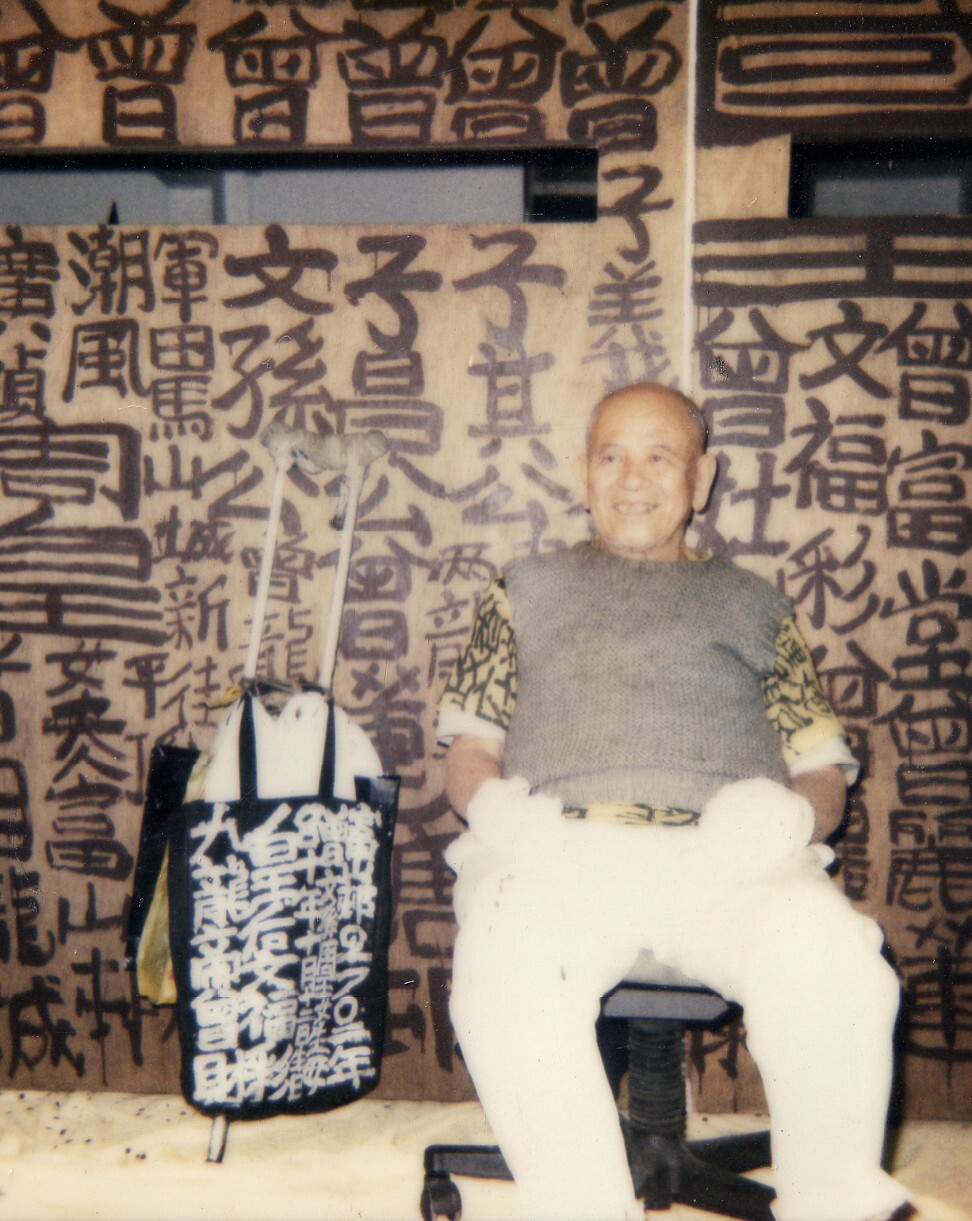

Tsang – who earned a pittance as a manual labourer and lived alone in a tiny, ramshackle flat in the industrial Kwun Tong neighbourhood – made an exhaustive study of his family tree and was convinced that most of Kowloon had belonged to his grandfather, hence his regal claim. However, he was unable to produce any official documents to support his claim.

He told the story to anyone who would listen, whether they were interested or not. His wife, Man Fok-choi, left him and other relatives shunned him. Undaunted, Tsang took to the streets with a campaign that was to endure for the best part of half a century.

Tsang used nothing more than a regular brush, the cheapest bottled ink and his own vivid imagination, while the streets of Hong Kong were his billboards.

Graffiti was almost non-existent in the city when he started out, but soon his idiosyncratic calligraphy and sometimes obscene pronouncements were etched on walls, pillars, postboxes, electricity junction boxes and any other surface that caught his eye all over the Kowloon peninsula. A pillar by the Star Ferry terminal in Tsim Sha Tsui is one of the few remaining public examples of his work.

Not everyone was amused by Tsang’s pictorial essays, although many thought they did little more than add a touch of humour to otherwise lacklustre public surfaces. From time to time he was arrested, and given a warning by police or a small fine. When his calligraphy was painted over, he’d return to write it all over again.

One magazine snidely labelled him one of the “10 least influential people in Hong Kong”. But then the art world started to sit up and take notice.

“I first met Tsang through a mutual acquaintance, and in time we became friends,” says Lau Kin-wai, one of Hong Kong’s most highly respected art critics and one of the few people who knew Tsang intimately.

“The content of his work was very simple – mainly confined to his family – and people interpreted it in different ways. It certainly inspired young artists, because nobody anywhere in the world had done anything quite like this before, and certainly not in Hong Kong,” Lau says.

“He was slightly unbalanced mentally, and I think it could be interpreted as a cry for help as his immediate family had disowned him. He suffered a lot.

“Sometimes he switched focus to comment on international matters, such as after the events of June 1989, and no doubt if he were alive now he’d have a definite opinion about what has been happening in Hong Kong over the past year. He spoke for the man in the street: he was the ultimate man in the street.”

His graffiti was very moving – he was communicating with the people, declaring what he felt about himself and about the government

Much like Tsang, anti-government protesters smothered Hong Kong’s streets with graffiti in 2019 amid calls to scrap a proposed extradition bill that would have allowed criminal suspects to be sent from Hong Kong to mainland China for trial.

Lau says he was pleased that the exhibition he organised in 1997 – which marked Tsang’s first proper recognition as an artist – was so well received. “There is no doubting his legacy, and his place as Hong Kong’s first graffiti artist,” he says.

The pre-handover exhibition at the Goethe-Institut attracted the attention of both local and international media, as well as those from the art world. The Swiss curator, critic and art historian Hans Ulrich Obrist, who wrote an introduction to a coffee-table book celebrating Tsang’s work, was immediately impressed.

“His graffiti was very moving – he was communicating with the people, declaring what he felt about himself and about the government,” says Obrist, who is currently artistic director at the Serpentine Galleries in London.

“His was a rough, raw message, enhanced by the compelling beauty of his calligraphy. During his lifetime, Hong Kong went through some extraordinary changes, and I think his work – some estimates put the total at more than 50,000 – reflected that.

“Certainly when I first came to Hong Kong in the 1990s you did not see much graffiti around, and I understand that before then there was practically none. Tsang was an urban poet, and he took art out into the streets where everyone could see it, unlike in a gallery, which always puts a barrier between what is on display and the viewing public.”

Besides painting the town, Tsang also employed more conventional materials, especially towards the end of his life when he was confined to a rest home.

Yet there was little impediment to his creativity or his line of thinking. One of more than a dozen of Tsang’s works in M+, which was created in the early 1990s, is a printed map of Kowloon that he emblazoned in marker pen with details of his family. The message is resoundingly clear: you may well have built streets and railways and skyscrapers – but you built them on top of my ancestral land.

“Tsang’s practice challenged many ideas about what constitutes works of art, design, artistic intervention in public space, alternative perspectives and diverse creative practices,” says Doryun Chong, deputy director, curatorial, and chief curator at M+.

“His work is difficult to categorise, as it expresses the multiple ways in which visual culture can exist, which is reflected in our museum’s multidisciplinary collections which encompass design and architecture, the moving image, visual art, and Hong Kong’s visual culture.

“It’s ironic that for many years Tsang’s work was considered a nuisance, but his unique form of visual expression has come to represent a local vernacular point of view during a period of transition from colonial rule that has made his perspective on identity all the more pertinent.”

Chong adds that the impact of Tsang’s calligraphy can also be measured in the way in which it has been appropriated by artists and designers in new creative works.

“Although the form of Tsang’s calligraphy shares some of the formal conventions of Chinese genealogies – in which he traced his own ancestry – his visual expression is entirely his own creative invention.

“[And] although it was once a prominent part of the urban landscape in Kowloon, like graffiti it was often viewed by the authorities as a nuisance and removed or painted over,” Chung says. “But today, his work is recognised as a significant part of Hong Kong’s intangible cultural heritage.”