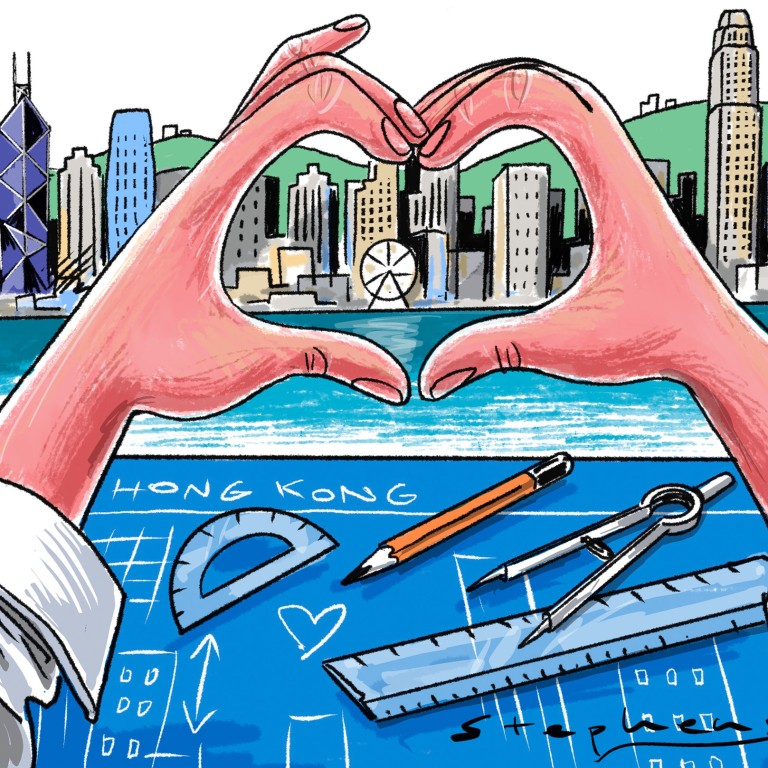

Like Singapore, Hong Kong can try to go beyond liveable to become lovable

- Singapore wants architects and urban planners to give more priority to intangible values like people’s sense of attachment, connection and inclusion

- Hong Kong can take a leaf out of Singapore’s playbook in thinking about the preservation of its buildings and spaces, and measuring success differently

Singapore and Hong Kong suffer from the same problem – we’re just not lovable enough. We may be viewed as ultra-modern metropolises that are the gateways to Asia. Perhaps even glitzy and glamorous.

Architects work with measurable, quantifiable and gradable standards. Calls for iconic or green buildings are typically met with plans for taller structures or carbon footprint calculations.

Design should address some of the most urgent issues in our everyday lives. Inclusion, connection and attachment affect all of us and should top the agenda for governments, societies and even businesses. In finding new and better ways to live sustainably, could architects and designers create spaces that embody these values?

In 2020 and 2021, the DesignSingapore Council conducted a study for The Loveable Singapore Project Report. The findings were distilled into a list of six intangible attributes that mattered most to people – agency, attachment, attraction, connection, freedom and inclusion.

The report put front and centre the community’s voices and reflections on the spaces they live, work and play in. It shifted the mindset of architects and planners, challenging them to go beyond design briefs and consider society’s needs and wants.

Getting to the bottom of that often starts with asking the right questions. Singapore sought to do just that at the Venice Architecture Biennale last year.

“When is Enough, Enough? The Performance of Measurement” was the title of the exhibition at the Singapore pavilion, where participants answered questions to help determine whether they felt any agency, attachment, attraction, connection, freedom or inclusion in spaces and buildings.

Harnessing visualising artificial intelligence (AI) software, artists created animations from thousands of frames, presented as interactive questionnaires. Looking at mash-ups of forests, public housing corridors, animals and everyday city scenes, visitors pondered questions such as: “How much should we tame nature?” and “When was the last time you felt like an outsider?”. The results were intriguing.

More than 97,000 visitors to the Singapore pavilion in Venice shared their thoughts with us and the data showed a strong appreciation for the preservation of heritage and nature.

For example, one in two respondents preferred old buildings to be experienced in their original condition or entirely subsumed into an eclectic district without discernible distinctions between modern and old.

We ran the exhibition again at this month’s Singapore Archifest and are collating the data. There is already enough evidence for us architects to consider a different approach. In the pursuit of the good, and the good for all, in the design of schools, homes and workplaces that make up our cities, we are guided by a multitude of standards and codes. But there are reasons we should consider alternatives.

Liveability has become less about the protection of local communities and more of a mainstream factor in the built environment and real estate market. Thus, it might no longer be enough to rely solely on the performance indicators that liveability indexes are comprised of. Expanding gauges beyond liveability is timely.

Seen in this light, the Lovable Singapore report is a study that could provide yet another playbook for innovation in design. Measuring concepts like connection to our community, attachment to places or the lived experience of agency to effect change in our surroundings could bring new frameworks for considering the success of projects.

This could be a pivotal time to align our work between the tangible and intangible, to more closely reflect, embody and foster society’s values.

Adrian Lai is a Singaporean architecture practitioner-educator, principal of MetaArchitecture and adjunct assistant professor at the National University of Singapore’s Department of Architecture