Rediscovering Macau: a timeless love affair with a city of hidden charms

A decades-long fascination with Macau has endured for historian Jason Wordie, who finds little of what matters to him has changed, post-Covid

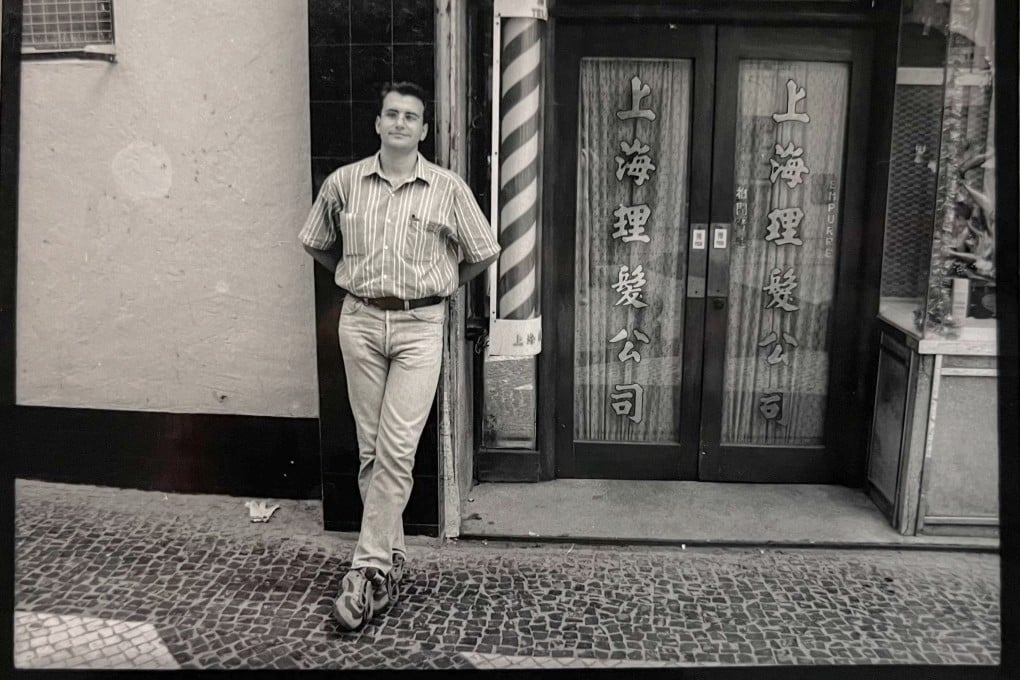

How does one even begin to describe a permanent yet intermittent love affair between a person and a place that has stretched on for decades? And do places cherished, somehow, in their own way, love one back? I think they do. Macau has been a much-loved constant in my life since my initial visit, aged not quite 22, back in 1988. From the very first day, I was strangely, mesmerisingly hooked by the place.

Not everyone understood what attracted me; to many in Hong Kong – then and now – Macau offered nothing more stimulating than a weekend’s worth of gambling, prostitutes and inexpensive Portuguese wine. When he learned about my regular visits, my then-boss, an avuncular British Army major, delivered a kind warning. After that, I kept my new enthusiasm carefully quiet until, eventually, I went to Hong Kong University to study history. There, my Macau research interests emerged from the shadows and, before long, broadened to include Hong Kong’s local Portuguese community – descendants of 19th century migrants from Macau, whose multifaceted legacy to Hong Kong endures.

In 1996, a partially completed manuscript about Macau’s lesser-known Portuguese monuments, mostly written by former HKU vice-chancellor Lindsay Ride, was passed to me by his widow, May. Pulling together The Voices of Macao Stones for publication opened up unexpected and enriching connections with personalities from an earlier Macau. Among many others, Monsignor Manuel Teixeira, aged doyen of Macau studies, was unfailingly helpful; an evocative watercolour of the Ruins of Saint Paul’s by White Russian refugee painter George Smirnoff, chosen for the book’s cover, led to his daughters becoming close personal friends.