Levelling Life’s Playing Field

[Sponsored Article]

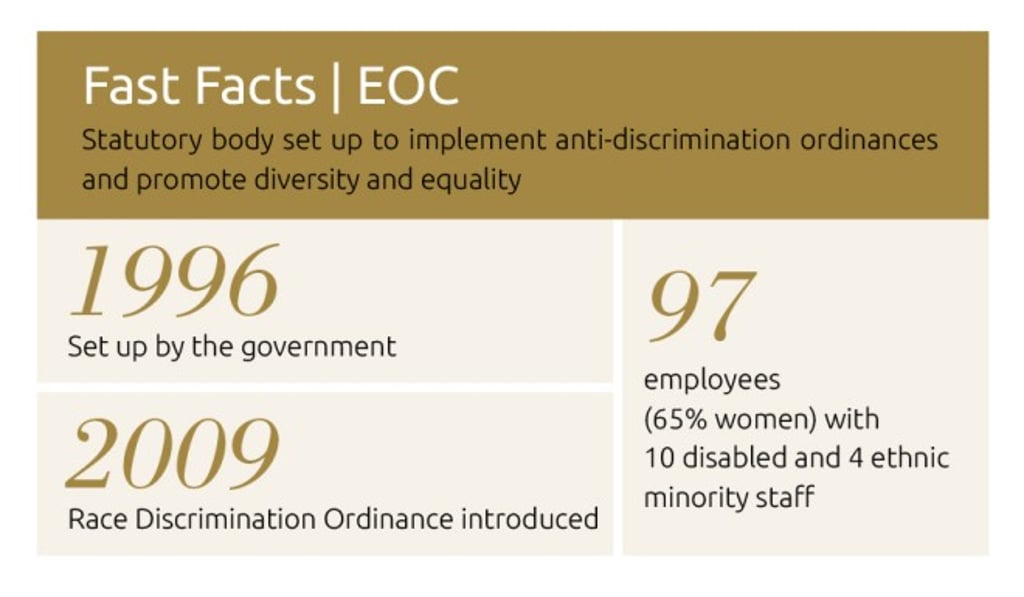

Making Hong Kong a fairer place takes time. It was only in 1996 that the city’s women won the right to the statutory paid holidays already enjoyed by men, with the introduction of the Sex Discrimination Ordinance. The government-funded Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) was established the same year. Since then, the commission has worked hard to promote equality of opportunity and an inclusive community.

“I think the most important landmarks in Hong Kong’s efforts to promote equality of opportunity are the establishment of four key pieces of legislation,” says Professor Alfred Chan Cheung Ming, who has been chairperson of the EOC since 2016. Along with the Sex Discrimination Ordinance, these include the Disability Discrimination Ordinance, which was also introduced in 1996. The Family Status Discrimination Ordinance was introduced in 1997, and the Race Discrimination Ordinance in 2009.

“In essence, all legislation is introduced as a reaction to the need at that time,” Chan notes. The debate over sex equality began in earnest in Hong Kong in the early 1960s, he explains, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that demands from the public, especially women’s groups, led the Hong Kong government to act to ensure fair treatment for women.

Race discrimination

Chan characterizes discrimination in Hong Kong as having two major components. One arises from the ignorance of individuals about, say, certain racial groups. The void left by this lack of knowledge is often filled by myths and stereotypes. There is also a systemic element due to government policies that fail to cater to the need of ethnic minorities. He cites Civil Service recruitment as an example.

“Even today, quite a few government departments, including the police force, still insist on Chinese language skills as one of the qualifications, regardless of the functional use of the language,” he says. This stipulation can cause hardship for Hong Kong-born members of ethnic minority communities who want to pursue careers as policemen, Chan adds. “However, we have been working with the government on this to make improvements,” he notes.

Based on figures from a range of sources, the EOC estimates the ethnic minority population in Hong Kong numbers around 250,000 (excluding foreign domestic workers), a very significant demographic. “The second and third generations within the minority communities were born here, and are legally Hongkongers. This group of people are highly educated, and more vocal than their parents’ generation, and they are asking for the same sort of training and employment schemes available to other young people in Hong Kong,” Chan says.

A personal perspective

Prior to taking up his position with the EOC, Chan spent many years working in the social services and education sectors. He says these experiences have informed his strategy in his current role.

“My social work background provided me with a bias towards empowering disadvantaged groups and protecting the weak. My background in education has left me totally convinced that, to be able to compete on an equal basis, you must have a sound educational base,” he says.

Chan says that groups end up disadvantaged if they don’t receive the necessary education and obtain the required qualifications, whether they come from the disabled, an ethnic minority, or other communities.

Looking to a fairer future

Chan admits that progress towards a more equal and inclusive society in Hong Kong has been slow. But he feels the pace of improvement has been accelerating, and he does see grounds for optimism. He believes the younger generation is much more accepting of differences, and the EOC can put effective pressure on government to implement positive change in areas such as training and employment.

Members of disadvantaged groups do not ask for special treatment, he points out, they just want the opportunity to compete on equal terms in an open employment market. “Members of the disabled community told us they didn’t want sheltered employment, as they saw this as sympathy, and they weren’t happy about that. They just wanted government to give then the opportunity to compete equally with others,” Chan says.

To help achieve this, the EOC is looking to promote recruitment processes that remove the element of human bias. The EOC itself employs a significant percentage of disabled staff, Chan adds, and there is a hard-nosed economic case to be made for this approach. “Evidence from Australia and Europe shows that an inclusive workforce, disabled or otherwise, achieves higher levels of productivity,” he says.

The important role the One Belt, One Road initiative will play in Hong Kong’s economic future adds further weight to this argument. “The countries that will be involved in this initiative do not speak Cantonese, but they do speak the languages of some of the ethnic minority groups in Hong Kong, such as Indian and Pakistani,” he says. “We have all these very able people here, so why not train them, and let them contribute?”