China’s Belt and Road Initiative Confronts Deglobalization

Evidence-based studies reveal why China and most Belt and Road countries remain committed to pursuing greater economic integration even with the forces of deglobalization in the form of the US-China trade war and ongoing geopolitical tussles.

By Chair Professor Albert PARK, Head, Department of Economics at HKUST Business School

[Sponsored article]

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) provides a broad framework for increasing China’s engagement and integration with the global economy. Announced in 2013, a major feature of the Initiative is Chinese support for large-scale infrastructure and investment projects in participating countries. However, just as momentum was building, the Initiative was confronted with powerful forces of deglobalization in the form of the US-China trade war and questions about supply chain dependence on China raised by the COVID-19 pandemic. How successful was the BRI before the recent turbulence, how has it been affected by the recent turn toward deglobalization, and can the Initiative help combat or reverse rising protectionist instincts? These are all important questions in considering the future direction of the global economy.

Unfortunately, debates about China’s Belt and Road Initiative have been highly polarized, rich in ideological rhetoric but typically devoid of evidence. Many in the West are highly critical, arguing that China seeks to exploit poorer countries and trap them in debt. China presents the Initiative as benevolent, supporting the development of countries around the world. Caught in between are the participating countries themselves, whose leaders often see an opportunity to finance needed infrastructure and attract foreign direct investment, but who also remain wary of excessive dependence on China and the need to balance international and domestic political interests that oppose closer ties with China.

More investment in BRI countries

In order to better inform our understanding of the implementation of the BRI based on evidence rather than rhetoric, I recently led research teams to complete two major projects on the BRI—one on “Trade and Investment Under the Belt and Road and Implications for Hong Kong” supported by Hong Kong’s Strategic Public Policy Research Scheme, and another on “The Belt and Road Initiative in ASEAN”, a collaboration between HKUST’s Institute for Emerging Market Studies and United Overseas Bank. These projects and related research have produced quantitative and qualitative findings that inform the questions just posed. Quantitative analysis utilizes micro-data on Chinese outbound FDI and construction projects in all countries from 2010 to 2019.

First, analysis of the project-level data finds that the BRI significantly increased Chinese investments in BRI countries (defined as the originally targeted 67 countries). Both FDI and construction projects increased by more than 50% in BRI countries after the Initiative began compared to changes in non-BRI countries. When we analyze the determinants of the flow of Chinese FDI to different countries before and after the Initiative began, we find that compared to the years before the BRI (2010-2013), since the BRI began the importance of economic fundamentals (such as GDP growth rates) has declined, while the importance of the countries’ governance quality (including measures of political stability, corruption, rule of law, regulatory quality, and government effectiveness) has increased. These findings suggest that outbound FDI flows are less profit-motivated under the BRI, raising concerns about their economic viability. At the same time, the greater importance of governance factors contradicts the narrative that China is seeking to exploit corrupt, poorly governed countries. Encouraged to make investments in BRI countries, many Chinese companies apparently seek to avoid countries with high governance risk. We find that this is true for investments by both state-owned firms and private firms.

What has been the impact of the BRI on international trade? A recent paper by Amber Yao LI, Associate Professor in the Department of Economics, and co-authors finds that the BRI significantly increases bilateral trade flows between BRI countries. The Initiative also increases the total trade volume of BRI countries, especially imports. With respect to trade with China, China’s imports from BRI countries increases after the Initiative, while exports from China to BRI countries do not change appreciably. These findings are consistent with China using FDI in BRI countries to secure access to resources (e.g., energy, minerals) or to outsource production of goods sold in China. The finding of positive trade impacts is important for two reasons. First, much research in economics has found a strong link between trade and growth. Second, if the BRI expands trade with member countries, it may have the potential to counter the trend towards deglobalization.

Diplomatic and economic objectives

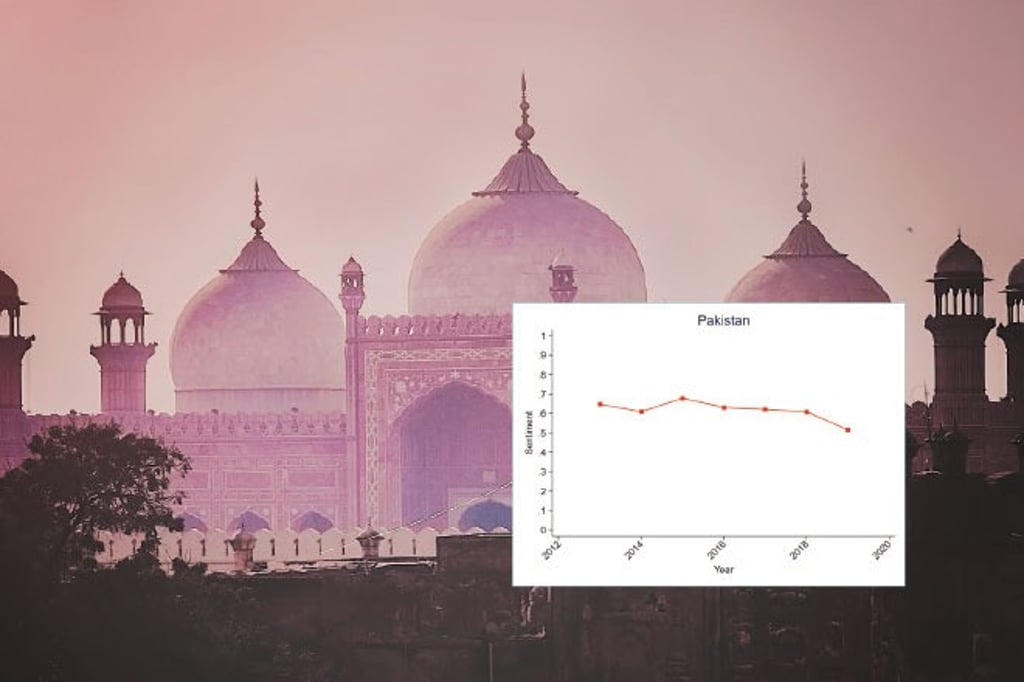

Since China’s objectives for the BRI are diplomatic as well as economic, it is of interest to ask whether the Initiative has increased China’s soft power. To shed light on this question, in an ongoing project with coauthors, I examine how sentiment towards China in different countries has been affected by the Initiative. Machine learning methods are used to analyze the positive or negative sentiment found in over one million media articles about China published globally from 2013 to 2019. We find that in most parts of the world, sentiment towards China has become increasingly negative in recent years. This is even true in countries receiving the most FDI from China under the BRI (Indonesia, Pakistan, Russia). Further analysis finds that sentiment towards China is inversely related to the amount of FDI or construction projects received from China. This negative correlation is more apparent when the FDI projects are in the resource sector, and when they are made by state-owned enterprises. Thus, China does not appear to be increasing its soft power through the BRI and may even be harming it.

Why would more Chinese investment in a country increase negative sentiment towards China even though there is evidence that the investments are having positive development impacts? Qualitative research in countries in Southeast Asia as well as other parts of the world finds that some Chinese projects are very unpopular locally because they harm the environment or have poor labor relations (for example, fail to obey local labor regulations or customary practices, or hire Chinese rather than local workers, etc.). Even one bad project in a country can attract considerable media attention and severely damage the reputation of Chinese firms. Opposition politicians may mobilize support by criticizing China or the close relationship between government leaders and China. China has drawn criticism from climate activists for being the only international donor that continues to finance coal energy projects. In many instances, China has funded projects requested by government leaders without doing sufficient due diligence to assess environmental and social impacts or to reach out to local communities. Some Chinese companies are gradually learning from their mistakes, by funding more renewable energy projects and focusing more on corporate social responsibility. A main conclusion from these findings is that if the BRI is to realize its lofty objectives, China would be well-advised to put greater priority on ensuring that Belt and Road projects meet high standards with respect to both economic viability and environmental and social impacts. The record of Western foreign aid programs to the developing world shows convincingly that money does not buy development.

A commitment to finish

How has deglobalization due to the US-China trade war and the pandemic affected the implementation of the BRI? A bilateral trade war naturally diverts economic activity to third party countries which actually could increase investment incentives in BRI countries. For example, Chinese companies and multinationals who manufacture goods in China and export them to the US have an incentive to relocate production from China to other countries to avoid punitive tariffs and diversify risk exposure. Producers in BRI countries may have greater opportunities to export to both China and the US. At the same time, if the trade conflict slows growth in the world’s two largest economies or spreads protectionism to other countries, this could have a chilling effect on foreign investment and trade globally. In this light, the recent signing of the world’s largest trade pact, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) signed by all ASEAN countries, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, demonstrates that countries in East Asia are committed to expanding rather reducing economic integration efforts. The agreement is complementary to the Belt and Road Initiative in that it facilitates globalization of supply chains and increases the benefits of trade and foreign investment.

Similarly, the leaders of most BRI countries have reaffirmed their commitment to completing major Belt and Road projects even if they are delayed due to the pandemic. Most infrastructure and investment projects were delayed by at least three to six months due to disruption caused by lockdowns, travel bans, and the preoccupation of government leaders and firm managers with responding to the crisis. The pandemic was a major economic shock to nearly all countries, even those that did a good job controlling the outbreak. This led many governments to re-prioritise spending commitments, which led to the cancellation of some BRI projects. On the other hand, some governments with sufficient resources, such as the Philippines, decided to increase infrastructure spending as a way to stimulate their economies. Many economies, including the US and China, are bouncing back strongly in 2021.

To sum up, China’s ambitious effort to promote greater connectivity with other countries through the BRI has created new infrastructure, increased investment, and expanded trade in BRI countries, but also has encountered criticisms that have undermined the Initiative’s ability to win hearts and minds in BRI countries. Nonetheless, the BRI is not going away any time soon. The recent turn towards deglobalization and growing anti-China sentiment create a challenging environment for the Initiative, but leaders in China and in most BRI countries remain committed to pursuing greater economic integration even as they adjust to a more confrontational and competitive relationship between the world two largest economies.

Media Sentiment Towards China in Belt and Road Countries Receiving the Most Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), 2013-2019

Reference

HKUST Institute for Emerging Market Studies and United Overseas Bank (2020). The Belt and Road Initiative in ASEAN. Authored by Albert Park, Dini Sejko, and Angela Tritto.

Diao, Wentian, and Albert Park (2021). Which Countries Have Benefited Most from China’s Belt and Road Initiative?, HKUST IEMS Working Paper No. 2021-79.

Lomas, Guenther, Albert Park, and Han Zhang, The Impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on China’s Soft Power, work in progress.

Bian, Ce, Jiaming He, Yao Amber Li, Weili Liu, Shiying Ou (2021). Does Belt-and-Road Initiative Promote Trade Flows? An Empirical Investigation, working paper.