Southeast Asia’s connectivity is critical to China’s belt and road … but can Asean pull it off?

Why links to Southeast Asia are so critical to China’s belt and road

[Brought to you by SCMP Events and Conferences]

Asia will remain the world’s fastest growing region and a true powerhouse of the global economy if Asean bloc nations, with the help of trade partner China, can realise cross-border integration and connectivity.

Although discussions about Asia’s tremendous growth in recent years often centre on economic giants India and China, Southeast Asia is quickly rising to become equally, if not more, promising.

Economic growth in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam – five members of the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations – is projected to exceed 5 per cent in the next decade, surpassing North Asia’s 3 per cent forecast.

Meanwhile, Asean has also surfaced as the world’s third largest labour force with a combined population of 650 million – the majority of which is still under the age of 40. Its middle class is rapidly expanding and increasingly better educated, and people are hungry for information and innovation.

But Asean nations remain geographically and culturally fragmented, with connectivity and integration eluding the bloc even after many years. And this is a key reason that investors remain cautious about buying into Asean firms or projects.

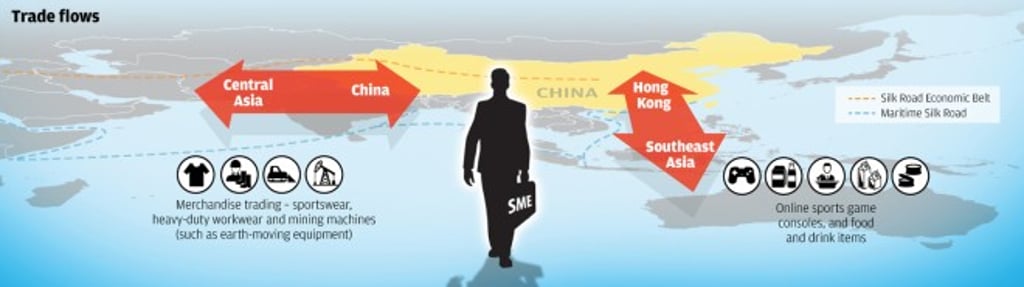

Cue China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”, which is focused on economic integration and connectivity across Southeast Asia and far beyond.

It’s been five years since Beijing unveiled its ambitious plan to forge a global trade route for Chinese goods and services by investing in strategic infrastructure projects abroad. A key part of the plan is Asean’s role.

China has long been Asean’s largest trading partner, with bilateral trade reaching a record high of US$514.8 billion in 2017. Both sides aim to double their trade volumes to US$1 trillion by 2020.

Enhancing land and sea connectivity with and between Southeast Asian nations has been central to China’s strategy in the region. On land, it has already launched a handful of railway projects, while at sea, Beijing envisions a ‘maritime Silk Road’ trade route that winds through the Indian Ocean and South Pacific to link up with Africa and Europe.

For instance, China has pledged the construction of a US$6 billion railway project with cash-starved Laos, which will link its capital Vientiane to China’s southern Yunnan province by 2020. The project, 70 per cent paid for by China, has been touted as critical to transforming landlocked Laos into a transport hub for the region, with railways eventually connecting it to countries such as Thailand and Malaysia.

Beijing’s focus on boosting connectivity between Southeast Asian nations is a potential game-changer for the region. Asean countries have long struggled to secure infrastructure financing, exacerbating not only their own domestic connectivity issues but also cross border trade.

China sees the belt and road projects as not only helping to resolve these issue, but also giving rise to developments in other sectors, such as support for infrastructure investments, wealth and risk management services, logistics management, legal and health care services.

But China’s plan does not stop there. It has also set its sights on enhancing digital connectivity and people-to-people exchanges as part of its belt and road. It hopes enhancing cross-border e-commerce and telecoms infrastructure in recipient countries – particularly neighbouring Southeast Asia – will unlock those countries’ potential.

In the online payments sector, for example, Chinese companies such as Alipay and WeChat Pay now provide financial services in markets such as Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia. Not only are these firms seeking to expand their own products across Southeast Asian region, capitalising on its growing middle class, but also to boost regional trade by giving Southeast Asian companies access to new Chinese markets.

And when it comes to people-to-people exchanges, Beijing is using its belt and road plan as a conduit to create more opportunities for people to improve their livelihoods, study or work in China, or for Chinese companies.

It’s no doubt that in times of global uncertainty about trade, the economic potential of China’s belt and road for Southeast Asia is massive. However, implementing it in a region that has long struggled to achieve cross-border connectivity may still prove difficult.

[This article has been expressly commissioned for SCMP events and conferences. This is not an SCMP editorial product.]