Teaching Empathy: How To Create Compassionate Classrooms

[Sponsored Article]

As educators and parents, we spend a lot of time focused on our children’s academics, extracurriculars, and test results. I suspect that “What did you learn at school today?” is a much more common question than “How did you feel at school today?”, let alone something like, “What did you do to brighten someone else’s day today?”. Sadly, much less time, effort and value are given to developing empathy and related skills such as self-awareness, respect, perspective taking, introspection, and active kindness.

I believe that empathy is the most important skill we can instill in our children. Empathy - a sense of shared humanity, and the ability to understand the needs and motivations of others - must play a central role in any school that aims to produce well-rounded, responsible and happy global citizens who will grow up to become tomorrow’s leaders.

That’s not to say that empathy should trump academics - the two are not mutually exclusive. Rather, there is enough emphasis on academics as is and empathy gets too little. If we do not teach our students the importance of empathy, then what kinds of future leaders will they become?

There is genuine cause for concern. With social media, we’ve seen the rise of filter bubbles or echo chambers, where people are drawn to only socialise with people like themselves and who share their views. The result is an empathy gap. In an age when confirmation bias pulls us into homogeneous bubbles, empathy may be the toughest quality to nurture.

The Harbour School (THS) was founded on the principles of kindness, compassion and humanity. With a strong belief in inclusion and diversity, the school has always placed enormous emphasis on social-emotional learning and the mental wellness of our students. At THS, our staff greet each student daily with kindness and warmth, they establish rapport and trust, and are positive role models for empathic, respectful behaviors. But is there more that we could do to unlock our students’ potential for empathy?

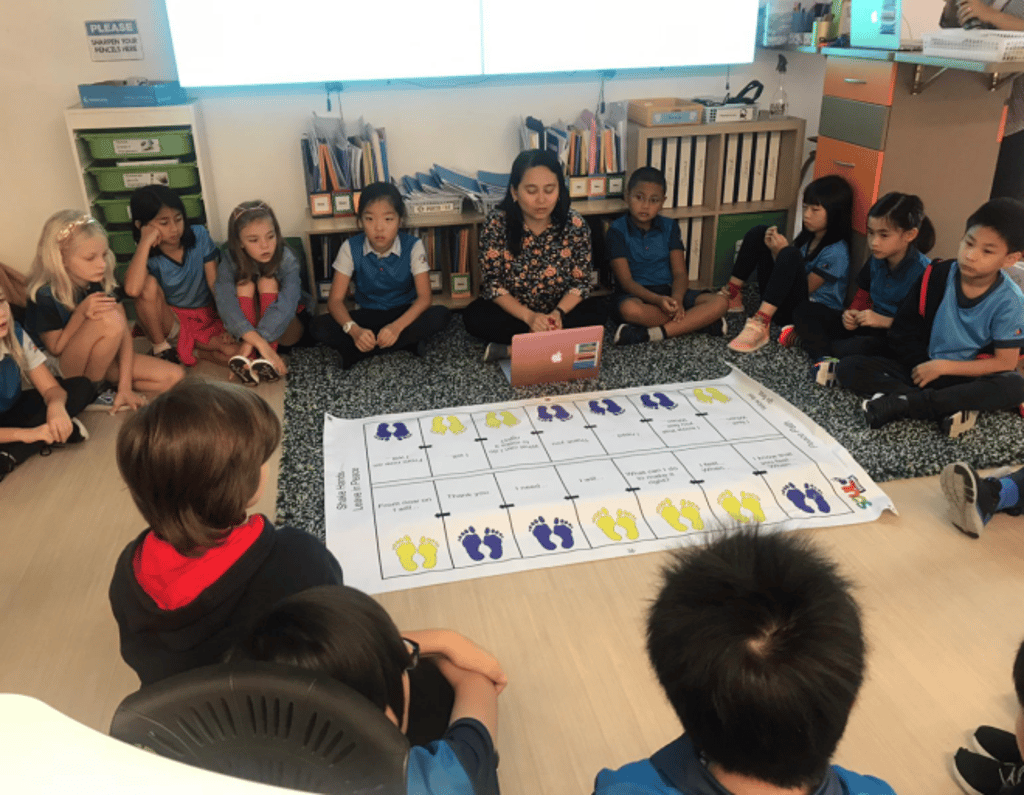

We want our students to be active listeners, develop a vocabulary for their feelings, listen to and understand others, increase their self-awareness and help them to regulate their emotions. It is a long list and no easy task. So two years ago, we decided to take it further. We implemented a curriculum and focused heavily on teaching students empathy starting from our youngest students in Prep.

1. Develop an “empathy curriculum”:

The program we introduced encourages a growth mindset, taking adversity as opportunity and giving students ‘tools’ to get unstuck, manage conflict, and develop respect for themselves and others. Through a variety of methods including role-play and by acting out scenarios, our students are taught to take into account the perspectives of others, to listen, and model supportive behavior. Teachers facilitate discussion on a wide range of empathy-related topics, build on the concepts taught, and continue to reinforce the learning in regular class and play time.

2. Create an empathic school culture with positive role models:

Whilst implementing a curriculum was important, that alone would not have been as impactful without a genuine culture of compassion and empathy observed by all in school. We’ve found that empathy cannot merely be taught didactically. It must be consistently modeled by teachers and staff.

3. Teaching self-reflection:

Recently, I was deeply moved by a conversation with a student who transferred from another school at the beginning of this academic year. In her previous school, she was a victim of bullying. On the day she came to talk to me, she was feeling down. She told me about her day and related incidents at school which had upset her. I asked her to help me understand the situation better, to which she responded that she had developed a good idea of what she observed was “the difference between teasing and taunting”. She explained that her mindset had slowly changed since joining THS. She explained that the bullying in her old school had been taunting which she describes as intentionally mean, deeply hurtful, targeted and ongoing. She said that it made her happy to know that she was getting better at engaging in playful banter without feeling hurt or resorting to being rude herself. I asked if her friends had noticed that she had been having a rough day, and she seemed almost surprised to think back and realize that they had in fact been giving her both a wider berth and deeper level of support than usual. You could see the gears turning as she looked back and understood the empathy she had been receiving. She walked out of my office grateful and happier. I sat in my office feeling a deep sense of pride towards our teachers and students who had helped her feel accepted for her thoughts and feelings. It was a clear example of the principles of empathy being alive and well in our student body.

4. Let students experience walking in another’s shoes:

Empathy should not be limited to only those immediately around us. We try to bring the same learning to our students about the wider world and their place as citizens in it which begins early at THS.

Each year, our Grade 2 students complete a cultural unit that tackles the global rights of children. Wider empathy comes with a sense of gratitude and appreciation for the things that we are lucky to have. While we thrive in relative comfort in Hong Kong, according to 2016 data from the World Health Organisation and Unicef, one in 10 of us globally still drink from unprotected water sources.

An example of a simple but powerful activity we carried out to help our students learn what this means was the Walking Distance and Drinking Water Challenge. Students walked one kilometre in the area near THS Grove campus. It was highlighted to them that some children walk four times more daily just to get to school. Moreover, these children also do not have convenient access to clean drinking water. When our students returned to class, they were presented with their “drinking water” - containers filled with filthy, muddy water. Our students thought about these children who are without ready access to what we deem is a basic human right. Such an exercise was profound in teaching empathy to our students.

5. Build empathetic courage:

If everyone believes or waits for someone else to take action, then it’s likely no one will. What then are we teaching our kids about responsibility? Diffusion of responsibility is an issue that we acknowledge and set out to tackle in our curriculum. By challenging our students to think about what it means to be an active bystander, or an ‘upstander’, and what does it take to demonstrate active kindness, we are setting them along the path of considering their actions or lack thereof.

The reverse is also true. Kids (and adults too) need to understand that sometimes we have thoughtless moments which lead us to either say or do things we are not proud of. This is not bullying. However, by recognising that you’ve used words that are unkind and then make an active change, you have already taken the path towards increased empathy. Self-reflection is key in this process. Teaching kids how not to constantly blame others for hurting their feelings and learning to differentiate what is bullying behaviour and what isn’t, is important. Equally as important is to actively ensure students also take time to reflect on whether they have been a passive bystander to a hurtful incident or not.

6. Teach active listening and looking through the eyes of others:

Research suggests that human beings are predisposed to behave selfishly. However, there is an equal volume of research and evidence that indicate the human brain is naturally wired to be empathetic. You will often hear from children, “It isn’t my fault” and “I didn’t even do anything wrong”. Sometimes it is true, and sometimes it isn’t. But how do we teach children to think about another’s point of view using perspective-taking? When children and adults discuss and practice the concept of empathy, they don’t personalize setbacks (Uche, 2010). Building empathy, resilience, grit and perseverance in our kids are important. When children can readily accept that things are not always going to go their way, they are cognizant that there are always other perceptions that can greatly differ from their own.

7. Embrace inclusion:

As adults, we work and socialise with all kinds of people, from all walks of life. Our ability to be able to work with others or indeed to create a service or product that would appeal to others is largely determined by our ability to understand the emotions and behaviours of other people and to listen to and see their perspectives. By working in mixed groups, it also challenges the assumptions and prejudices that we have about others based on their appearance, accents or backgrounds.

So why do we keep students in homogeneous groupings at school? As we’ve seen at THS, when a diverse population of students that vary culturally, neurologically, and ethnically are put into a variety of mixed-ability and mixed-age classrooms, empathy is naturally elevated. It is that critical quality which allows students to understand and listen to each other’s perspectives, feelings, and desires, and by doing so, better understand their own. When empathy is taught well, it empowers children to work cohesively, support each other’s learning, and even resolve their own conflicts.

While creating a rich and challenging learning environment that is supportive to academic goals is important, it must go hand in hand with a nurturing environment surrounded by positive models who actively encourage students to take the empathetic path and to listen to and see the perspectives of others. It must also allow students to make mistakes, to be there for them and to learn resiliency through disappointment.

About Natalie Mierczak, THS Prep, Primary & Middle School Vice Principal

Natalie has a Bachelor of Education degree from the University of Sydney and taught at one of the largest special needs schools in Australia for 12 years. She presented at a nationwide leaders conference on using augmentative and alternative communication for students with Autism. She has an honours degree in Special Education and began her career teaching in EDBD schools (Emotional and Behaviour Disturbance). She has been at The Harbour School for 3 years and has been the Vice Principal for 2.5 years.