Designing courses for the future of learning

[Sponsored Article]

The notion of “interdisciplinary learning” is not a novel one. It has long been acknowledged that in a real-world context the content of discrete subject areas such as History and Literature or Chemistry and Calculus necessarily collide. And one will hear many secondary school educators and administrators cite the virtues of teaching courses in which content authentically combines.

For how complete can one’s analysis of Shakespeare be without cultivating an understanding of the politics of the Elizabethan city and stage? Or how thorough a study of how diseases spread without examining sociological factors alongside the biological? And how valuable is a schooling experience if it promotes artificial categories of knowledge?

It seems a common understanding that academic content in the “real world” is by nature interdisciplinary and the will to evolve secondary schools from places where the nuances of content knowledge and skills are often stifled by stratification into integrated centers of learning has existed amongst practitioners for decades. Yet the practical setup of schools frequently renders such objectives elusive if not impossible to achieve.

In a conversation characterized by trendy terminology such as “innovative” and and “futuristic,” a deep dive into the logistics of curricular change is not always the most attractive. When conceiving of different ways of approaching academic content, the tendency is to hone in on new and improved pedagogies without much concern for how everyday procedural elements of schools can have the biggest impact on moving the progressive education ball down the field.

How, for example, are a mathematics and literacy teacher meant to collaborate when they so often are assigned to different areas of the building, operate on conflicting schedules, and are expected to use planning time to attend department-specific meetings. No amount of investment in collaboration across disciplines will yield change subject to these limitations of time and space.

The Harbour School, founded as a seven-student pre-school in Kennedy Town ten years ago, has expanded to include nearly four hundred students, grades Pre-K through 12, across three campuses on Hong Kong island. THS’ integrated approach to learning, in which teachers are encouraged to emphasize the real-world application of content, faces the same challenges at the secondary level as any other school might when looking to integrate disciplines.

While THS strategically hires for individuals who see themselves as being curators of experiences as much as purveyors of content, strong high school teachers are by nature specialists - often deeply invested in one or a subset of content areas. As such, THS focuses on the ways in which it can make all of the logistics of its academic program - from timetables to the course design process - work for its vision, rather than the other way around.

A peek inside the high school’s course catalog will give you a clue to how this is accomplished. In it you will find classes ranging from a classic Calculus or Intermediate French course to offerings entitled A Hong Kong Atlas, Amusement Park Physics, or the remarkably popular Because Jellicles Can and Jellicles Do: But Why And Can You? (for those like me who didn’t catch the reference, Google the musical Cats and the T.S. Eliot poems which inspired them).

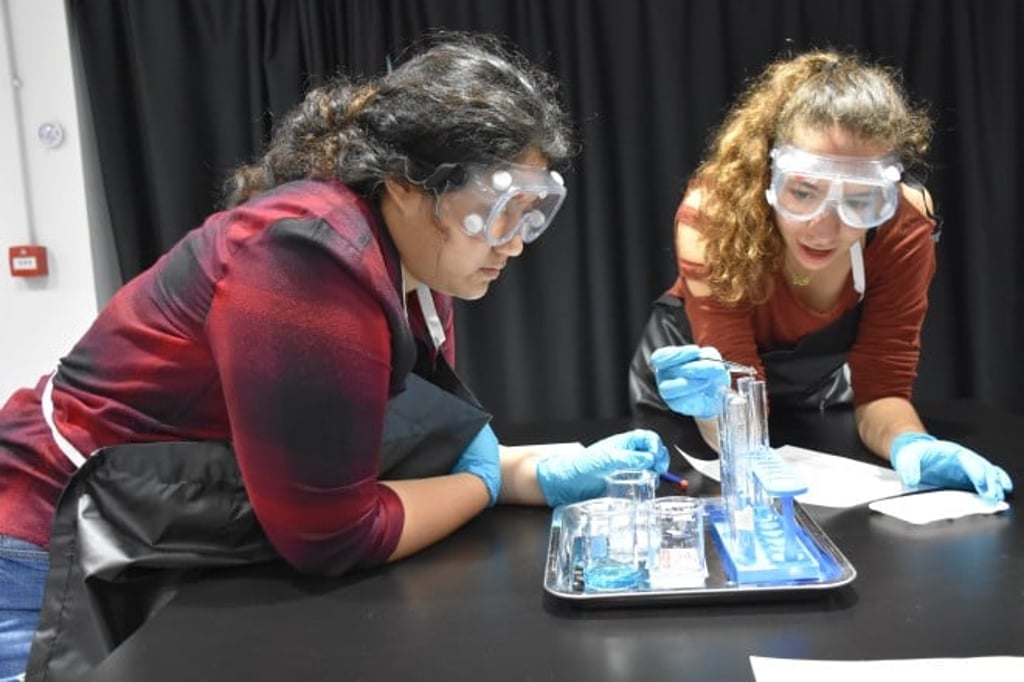

The more elaborate titles signal interdisciplinary courses in which faculty from two to three departments are given the opportunity to develop curriculum that authentically weaves their respective content areas together. Their schedules are built to support this endeavor through common planning time assigned by teaching team rather than department. Pairing teachers from the onset of the course design process and requiring them to link their respective contents via a unified narrative ensures more authentic integration.

Courses are tagged for credit according to prioritized content, with one course often carrying multiple tags. In order for students to have the option to take, for example, Food Chemistry for either Science or Social Studies credit, the course must include a balance of relevant academic objectives from both areas.

It would, perhaps, be simpler for an instructor to teach a standard Chemistry course in which one unit is dedicated to the science of cooking or food preservation. But working with a specialist in a different content area requires them to think deeply about the value of their own expertise in a broader context, a context which is then employed to engage students with a wider range of interests.

It is common, for example, to find that students see themselves as this or that “kind” of learner. Statements like “I am terrible at math,” are often byproducts of educational systems that isolate disciplines in arbitrary ways - allowing students only one avenue for approaching an academic discipline.

A course like Angles, Art, and Mathematics is designed to demonstrate to a student who performs well in visual art classes but claims to detest math that they might employ their understanding of figure drawing to master the principles of geometry and vice versa. The priority becomes about engaging the students one has right in front of them in developing an authentic interest in the academic content as they might engage with it in future studies or career pursuits.

If students, teachers, and parents desire to promote educational experiences which engage students via their interests, emphasize the practical applications of academic content, and break down arbitrary silos of knowledge and skills, they must examine whether the logistics of the course design process allow for or prohibit these objectives.

About Dr. Elizabeth Micci, THS High School Principal

Elizabeth joined The Harbour School in 2017 as a researcher and a member of the high school humanities faculty while completing her Doctorate of Education Leadership from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Upon completion of her program, she became the High School Principal at the Garden Campus. She also holds a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration and English from Washington & Lee University and a Master of Arts in English from Middlebury College. Prior to joining The Harbour School, Elizabeth was a high school English teacher and administrator of a college prep academy in Houston, TX.