Cord-cutting was already the norm in China when the coronavirus hit, as people turn to the likes of iQiyi, Tencent Video and Youku

- Deregulation in 2014 brought sports to streaming services, permanently changing the industry

- Many Chinese households only use streaming for TV, typically paying less than US$5 a month

Li Ming first moved to Shenzhen in 2013, just as streaming services were becoming more popular in China. But Li thought using streaming as her sole source of TV would be troublesome. So just as she had in Guangzhou, Li signed up for a local cable service – a more popular option in the affordable urban village where she lived.

Seven years later, things are very different. And not just in Shenzhen.

“Who uses cable TV now?” Li said. “Now everyone likes streaming. Even my grandma can use streaming.”

Like in the US, ditching cable for streaming is increasingly common. But unlike in the US, cord-cutting in China is more about convenience as most people can get everything they want online.

Li’s grandmother aside, many older people in China are holding on to cable. It still has the most subscribers of any pay-TV option. But that’s changing fast. By 2021, it’s projected to lose out to IPTV, according to a report from GlobalData. IPTV is another service similar to cable that delivers content over a dedicated internet protocol network.

Some people prefer the familiarity of IPTV, but younger people have been flocking to streaming services for years. After all, relying on a single dedicated box to deliver TV content seems outdated these days. Many viewers might prefer watching content on a phone while on the go, picking up on a tablet while lying in bed, and maybe flinging it to a TV when convenient.

“Now I don’t even use a TV box,” Li said. “My TV has Wi-fi, and I project shows from my phone.”

Li switched to streaming back in 2014, but she still considers herself a late adopter.

“I could be considered slow to change [to streaming]," she said. “Early adopters were using LeTV and Xiaomi boxes for a while when I was still using cable because I was lazy and didn’t understand [the apps].”

Compared with most of China, Li wasn’t really behind the curve. The year she cut the cord was also the year the industry started undergoing rapid change.

That’s when China issued new guidelines leading to the deregulation of the the sports sector, ending the monopoly on sports broadcasting for state broadcaster CCTV. This allowed other companies to bid on the rights for foreign sporting events like the Olympics and the World Cup.

This was a game changer for streaming services, known in the industry as over-the-top (OTT) services because they run over the internet.

“Sports is being increasingly driven by OTT in China rather than by TV,” said Adrian Tong, senior analyst at Media Partners Asia. “Following deregulation of the sports sector in 2014, key media and digital companies land-grabbed key sports rights in the country, driving up digital fees in recent years.”

This might not matter much to Li, who says she mostly sticks with variety shows and dramas. But this changed how China’s legions of National Basketball Association (NBA) fans were able to watch their favourite athletes.

The NBA is hugely popular in China, drawing 800 million viewers during the 2018-2019 season. To keep all those avid streamers when its contract with the NBA was up last year, Tencent possibly paid as much as US$1.5 billion for another five years by one estimate.

The regulatory change helped make Tencent Video a giant in sports streaming. Chinese streaming pioneer LeTV also spent a fortune on exclusive sports streaming rights before running into financial problems, Tong said.

This change was pivotal for how streaming developed in China over the last several years. People in China no longer switch to streaming because it’s cheaper. It’s often not. Cable might cost just US$3 or US$4 per month while streaming services cost US$3 to US$5, according to Tong. Many people in China switch to streaming just because it’s better.

For many Westerners, cord-cutting is still associated with saving money. In the US, some people pay upwards of US$200 per month for cable TV. One big reason for that is live sports, as became abundantly clear this year when cord-cutting accelerated because many sporting events were cancelled or postponed due to the coronavirus. Long-entrenched relationships between sports leagues and networks in the country have been the lifeblood of the industry.

To save money, Americans might turn to websites, guides and forums preaching a cord-cutting lifestyle. China doesn’t have this phenomenon largely because many people already see streaming as synonymous with TV.

This doesn’t mean streaming is a perfect substitute for cable in China, though. Some people insist that there is still some content that can only be found on cable.

Under a question on Q&A site Zhihu asking for a comparison of IPTV and cable, some people said they need cable to watch certain live sports on the channel CCTV5. There were also multiple posts defending the picture quality and stability of cable TV.

“If you want to watch all kinds of CCTV5 sports live broadcasts, there’s no need to think about it,” one person wrote. “You have to go with cable TV.”

Yiming Zhang, a 33-year-old translator in Beijing, said her parents still use cable TV in Tianjin, a city southeast of the nation’s capital.

“We still have to use cable, otherwise we are not able to have normal TV channels and live programs,” she said. She added that older people may use cable for local news channels.

For people like 31-year-old Li, that’s never been a problem. Even though a lot of CCTV news content can now be found online, Li said she never watched it and doesn’t need it on her streaming services.

Many provincial news channels are also available on IPTV, according to Tong, and there are other ways of accessing local news. This is certainly true for younger consumers. A lot of news consumption has already been driven online to platforms like Toutiao, China’s dominant news app.

Other online comments seem more in line with Li’s views. Under a Weibo post about cable TV subscribers falling by nearly 2 million households in the first quarter, many commenters herald the coming of the internet TV age.

“Now all [TVs] are smart TVs, it’s convenient to watch anything,” one person commented.

“It's the internet TV era now,” another said.

Many of China’s most-viewed TV programs are now streaming exclusives, showing up on platforms like Baidu’s iQiyi, Alibaba’s Youku and Tencent Video.

(South China Morning Post is owned by Alibaba.)

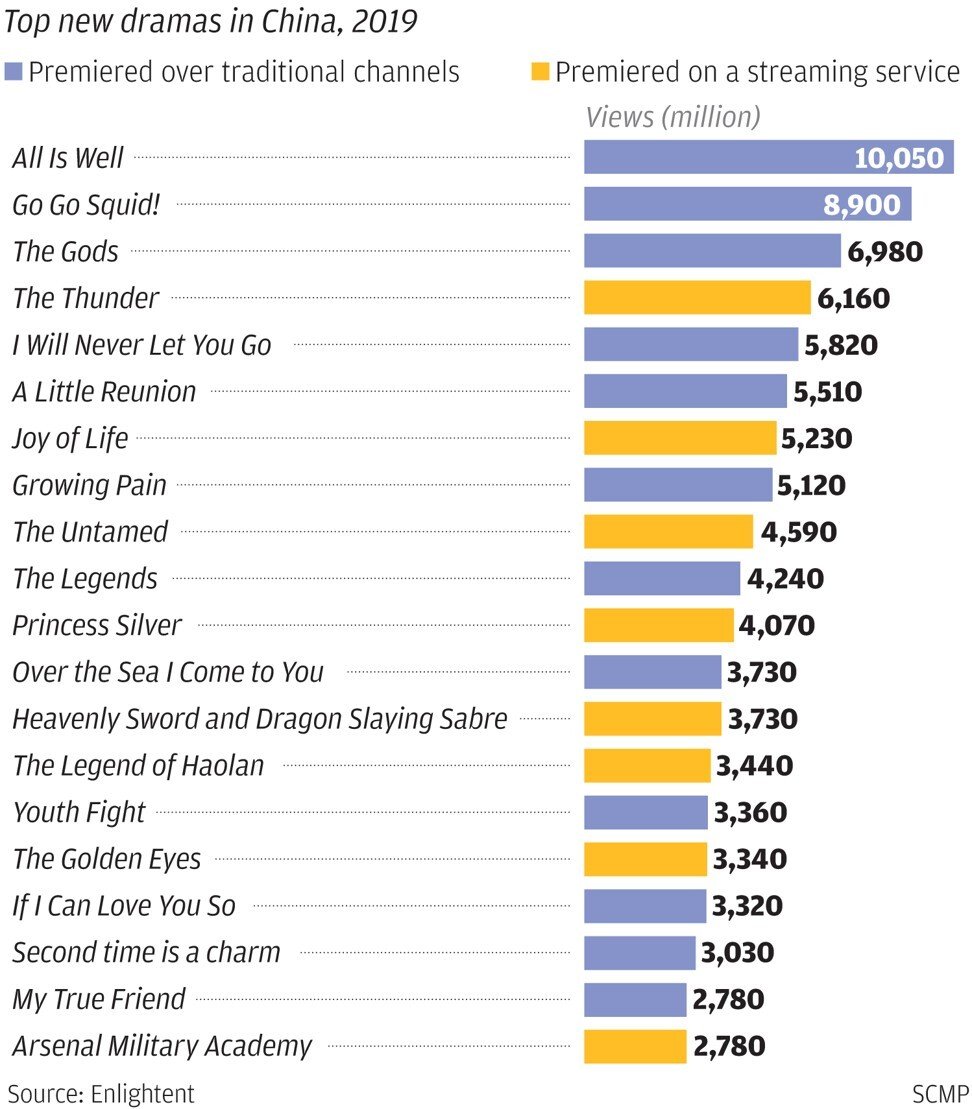

Eight of the top 20 shows in China last year premiered online, according to data analytics firm Enlightent. But instead of tuning in to binge The Witcher on Netflix or The Handmaid’s Tale on Hulu, China turns to shows like The Thunder on iQiyi or The Untamed on Tencent Video.

Like their American counterparts, Chinese streaming services are investing heavily in new content. They’ve also used the Covid-19 pandemic as an opportunity to try to bring in more viewers with things like virtual film festivals, showing hot new films that can no longer open in theatres, and rapidly pushing out low-budget fare that appeals to genre aficionados.

It helps that viewers in China can access all this content for a fraction of what American subscribers pay. At US$5, that’s just half a percent of the average monthly salary in China in 2018. That same year, the average cable bill in the US was closer to 2 per cent of median American income.

In China, it’s not unusual for people to have both streaming and cable or IPTV. The biggest trend towards cord-cutting is in less-affluent neighbourhoods, according to Tong. It’s largely more price-sensitive consumers who are choosing to ditch cable.

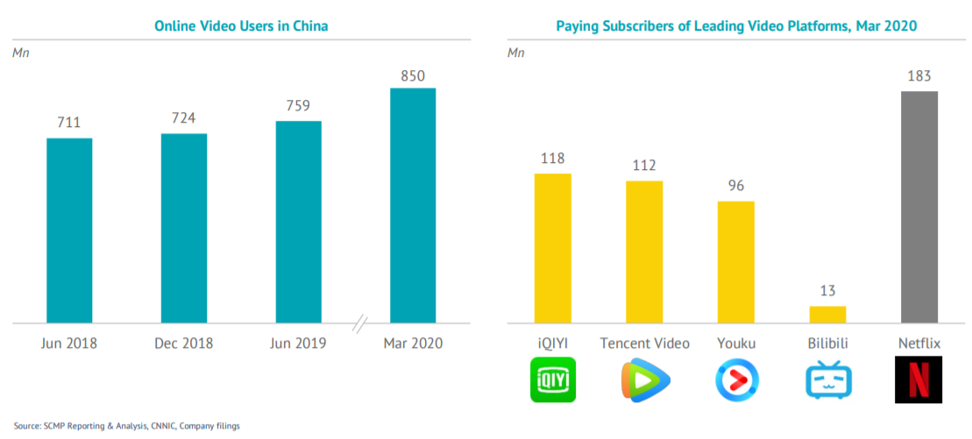

China now has 850 million online video users. The total number of paying accounts for iQiyi, Tencent Video, Youku and Bilibili is 339 million, slightly larger than the entire population of the US, with many subscribers paying for more than one service. By comparison, China now has just 142 million cable TV subscribers.

There’s also another side to cord-cutting in China: Many of the people leaving cable behind are really just giving it up for IPTV, which looks and behaves an awful lot like cable. For some people, this is a feature, not a bug. Older users could find something comforting in the channel-based system delivered through a TV box.

“We use both IPTV and internet TV,” said Jessie Xiao, a 40-year-old insurance broker in Shenzhen, adding that IPTV was for her parents. “It’s easy to control for them and free.”

IPTV’s secret weapon in China is that it often doesn’t cost users anything. Telecom companies typically offer internet service bundles that include IPTV at no additional monthly cost.

This has arguably had the biggest impact on cable companies. Revenue for China’s cable TV networks has been slowing for years, and it’s been in decline since 2017. Revenue fell by more than 8 per cent that year and another 7 per cent in 2018 to about US$11 billion, according to data from China’s National Radio and Television Administration.

But not even giving away free TV service is enough to entice people away from streaming. Xiao said she and her husband prefer streaming services because they offer better content. And Li, who said she once used free streaming apps to save money, now subscribes to Tencent Video.

Despite rapid user growth, the industry’s fierce competition remains the same. The competition in the streaming space could subside some if Tencent ever achieves its desired majority stake in iQiyi by buying out Baidu’s stake. Even so, GlobalData projects that pay TV revenue in China will decline at a compound annual growth rate of 1.2 per cent from 2019 to 2024. Subscriptions will decline 5.7 per cent.

That might be where TV in China and the US start to look similar again. It seems both countries are living in the golden age of TV, with a plethora of quality content and consumer choice. But actually making money from all that content is a different matter. Streaming companies in the US are racking up massive debts in a content arms race. And expensive content is part of the reason that OTT services are rising in price, rivalling cable TV prices in some cases.

So it looks like we all have to enjoy the cheap content while it lasts, whether we’re watching The Witcher or The Thunder.