True level of bad loans is far higher than Beijing admits

While no one believes official line, no amount of statistical flexibility will ease the impact when problems mount in tandem with slowing economy

When Chinese regulators said earlier this week that non-performing loans on the mainland amount to less than 1 per cent of total bank lending, no one believed a word they said.

Officially, mainland banks' asset quality is super-solid. At the end of June, the value of commercial bank loans classed as sub-standard, doubtful or in loss came to 540 billion yuan (HK$678.9 billion).

That means just 0.7 per cent of Chinese banks' local and foreign currency loan books is deemed to be non-performing. In comparison, the ratio in Japan is 2.9 per cent.

In any case, according to their financial statements, Chinese banks have made ample provisions against loan losses, setting aside almost 1.6 trillion yuan, enough to cover their current bad loans nearly three times over.

The trouble is no one believes the official figures are an accurate guide to Chinese banks' asset quality.

If a state sector banker lends 10 billion yuan to a local government-owned aluminium smelter for three years, and at the end of that time the company is unable to pay him back, he just lends another 10 billion yuan so it can repay the original loan. That way no one gets embarrassed by any non-performing loans.

With little reliable information about bank credit procedures or the quality of their loan books, working out just how many loans would now be classed as non-performing had they not been rolled over in this fashion is impossible.

However, given that China's total outstanding loans have more than doubled in value since 2008, it is simply not credible that bad loans should have fallen by 20 billion yuan over the same period.

Indeed, banking analysts point out that China's continued credit accumulation is evidence in itself that large numbers of loans are being rolled over rather than repaid.

While this forbearance might sound generous, it is a big problem. Rolling over loans to zombie companies crowds more productive borrowers out of the market, stifling business activity.

The worry now is that as the economy slows, more and more companies that borrowed large sums anticipating growth rates of 10 per cent will find themselves running into repayment difficulties, and that the true level of non-performing loans in the banking system will rise sharply.

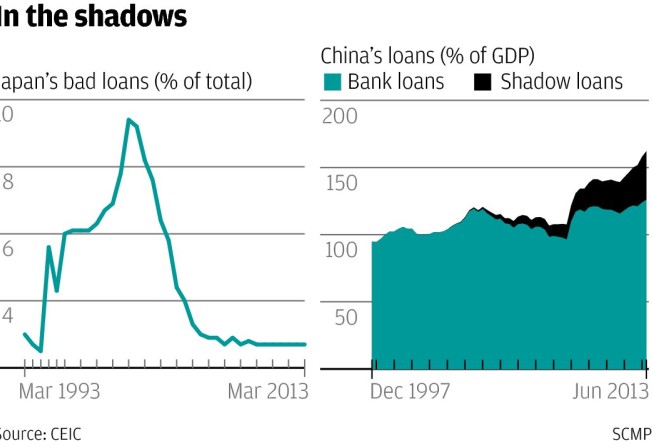

Again, estimating with any confidence how big the problem might get is tricky. But historical precedents can provide some guide. Between the late 1980s and the mid-1990s, Japan's growth rate fell by around half. Japanese banks, too, were slow to recognise the extent of their non-performing loans, but when eventually they were pushed to it by the government, bad loans climbed to 9.5 per cent of their total (see the first chart).

The ratio in China is likely to be higher. Even at the height of Japan's credit boom, the value of outstanding bank loans only reached 104 per cent of gross domestic product.

China shot past that level years ago, with outstanding bank loans now reaching 126 per cent of GDP. And if you add in off-balance sheet shadow market lending, much of which may eventually end up back on banks' balance sheets, China's total outstanding loans now stand at more than 160 per cent of GDP.

The faster the credit expansion, and the greater the loan-to-GDP ratio, the higher bad loan levels are likely to climb in the event of an economic slowdown.

As a result, if China's growth rate slows to an annual 5 per cent over the next few years, which many economists believe likely, it is reasonable to conclude that the bad loan ratio will rise to exceed 10 per cent of total bank loans.

Of course, it's possible neither the banks nor the regulators will admit to such a high proportion of non-performing assets.

But no one believes them anyway.