Why do Hongkongers pay sky-high prices for petrol when international oil remains at multi-year lows?

- The cost of land on which petrol filling stations are built has risen by over 400 per cent in the last 10 years

- Fuel retailers say there are a range of factors for the delay in lower prices to be reflected at the pump, including high inventory levels, government tax, salaries and land costs

International oil prices may have declined to multi-year lows, but Hongkongers continue to pay elevated prices for petrol. In fact, Hong Kong has the dubious distinction of having the highest pump prices in the world.

Industry observers say this is mainly due to surging land costs for building fuel stations, which have increased by more than 400 per cent in the past decade, thanks to Chinese oil companies’ rampant expansion.

Even as crude prices remain depressed amid an all-out price war between the world’s top producers Saudi Arabia and Russia, and sinking demand due to the coronavirus pandemic, there is a time lag for lower prices to be reflected at the pump due to retailers’ inventory-keeping and other costs, say operators.

“Besides, import cost, government duty, land costs, wages, marketing and overhead expenses all impact our retail pump prices,” said a Shell Hong Kong spokesman. “Indeed, the increase in land costs has been much higher than other costs.”

Petrol retailing in Hong Kong is dominated by five players – ExxonMobil’s Esso, Chevron’s Caltex, Shell, Sinopec and PetroChina – which operate 182 fuel stations between them. Sinopec and PetroChina both started their retailing operations in 2004.

At US$2.15 per litre on Monday, the price of petrol in Hong Kong was 131 per cent higher than the international average, according to globalpetrolprices.com, which compiles prices from 164 nations. Of the retail price, nearly 40 per cent of the pump price or HK$6.06 per litre goes to the government in the form of fuel tax.

No free oil for China after US benchmark WTI price fell below zero for first time ever, say analysts

Vincent Cheung, managing director of Vincorn Consulting and Appraisal, said the high land prices for petrol stations have been largely driven by Chinese majors, as they have spent a lot to expand their market share.

The government leases land to operators of petrol filling stations for a period of 21 years. It has also taken a series of measures to facilitate the new entrants achieve scale.

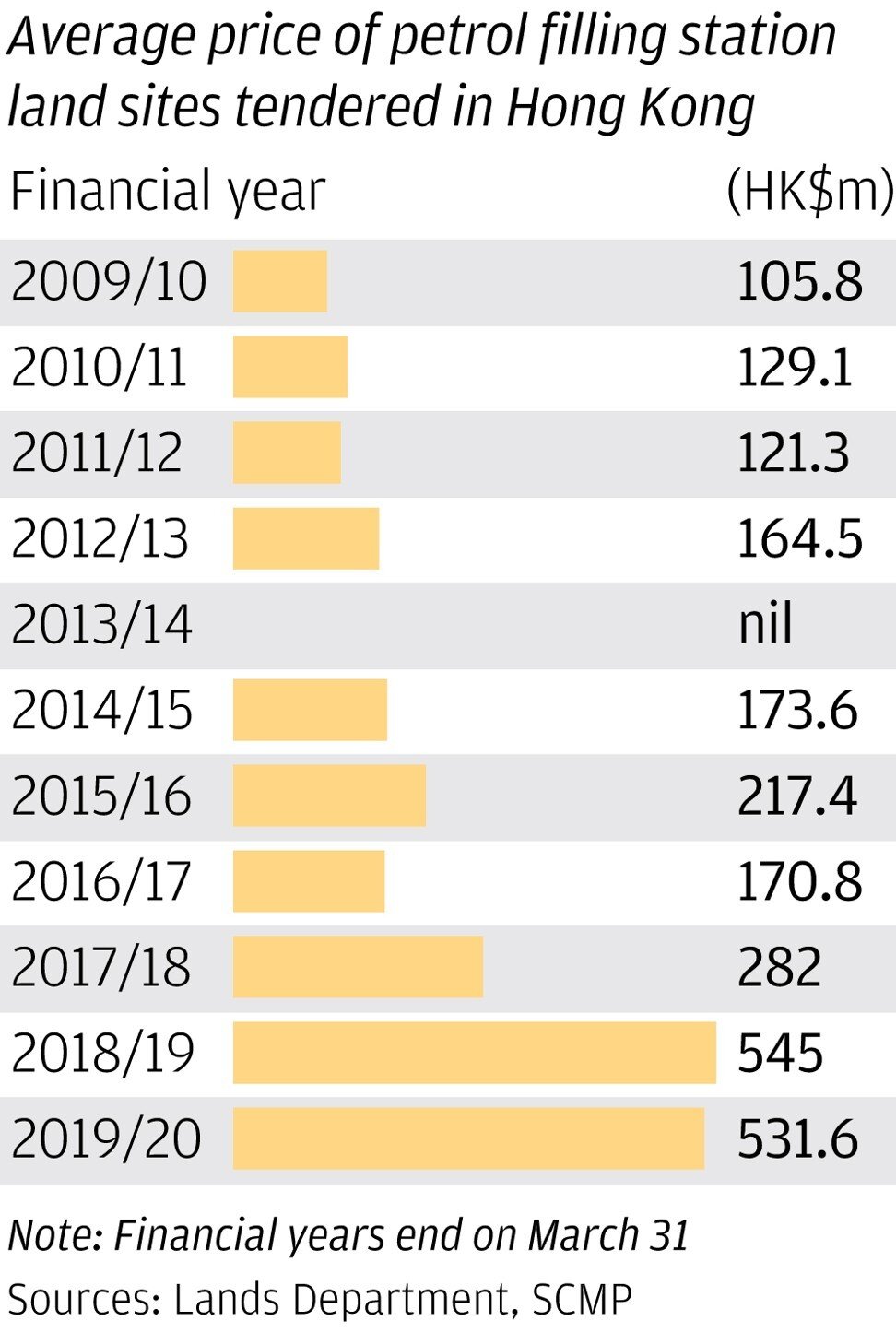

The average winning bid for a fuel station site has risen to HK$531.6 million (US$68.6 million) in the 12 months to March 2020 from HK$105.8 million in the same period in 2010, an increase of 402 per cent, according to Lands Department data. In 2019, the price stood at a record HK$545 million.

Land lease accounts for up to 70 per cent of the total cost of some fuel stations, said Hannah Jeong, head of valuation and advisory services at Colliers International. She said international petrol companies have indicated that they are finding it tough to compete with cash-rich mainland companies who continue to bid up land prices.

Alnwick Chan, chairman of the general practice division of the Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors, estimates that land cost could account for more than 90 per cent of the total fixed cost of a fuel station, as constructing a petrol station with storage tanks amounts to between HK$10 and HK$15 million compared to the land value of around HK$500 million.

PetroChina declined to comment on its Hong Kong strategy. Sinopec’s Hong Kong spokesman said its presence in Hong Kong has promoted fuel retail market competition and created “a better option for the consumers”, adding it has launched several promotional offers to different types of consumers during the pandemic.

Chinese oil giants’ expansion in Hong Kong is part of Beijing’s ongoing outward globalisation strategy, said Kevin Tsui, associate professor of economics at Clemson University in the US and a researcher at Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

PetroChina will add five more stations to its 12 in the year’s second half. It is the most aggressive of the five fuel retailers, spending HK$3.75 billion for 11 sites sold by government tender since April 2009. Sinopec’s expansion plans, which operates 42 fuel stations, are unclear.

The rapid expansion of PetroChina and Sinopec have already made a dent in the operations of the other three players – Esso, Caltex and Shell. The trio now operate 44, 34 and 40 fuel stations, respectively, accounting for 70 per cent of such outlets in the city compared to 93 per cent 15 years ago.

The seven-day moving average price of regular unleaded petrol at the pump – excluding duty and before consumer discounts – has fallen 7.2 per cent from HK$18 a litre in late January to around HK$16.7 in the middle of this month, data collated by the Environment Bureau showed. Discounts, which can change from day to day, varied from Caltex's 90 cents a litre to Sinopec's HK$3 on Saturday, according to the Consumer Council.

Meanwhile, the seven-day moving average of regional export price benchmark “Mean of Platts Singapore” has plummeted about 70 per cent from HK$3.75 to HK$1.2 in the same period, according to the Environment Bureau.

It is no wonder consumers complain about the disparity in international oil prices and prices at the pump.

“Criticism of oil companies’ ‘fast hike, slow cut’ of pump prices is not unique to Hong Kong, it is a worldwide phenomenon,” said Tsui, who has studied fuel markets. “This is an issue even in the US where the market is big, fuel tax is low, land is cheap, and legislation is there to prevent collusion, which is extremely hard to prove unless there is explicit communication evidence of price fixing.”

He attributed Hong Kong’s ‘fast hike, slow cut’ phenomenon to the high fixed cost structure of fuel stations, similar to restaurants where prices do not fall much even when the cost of food ingredients falls substantially.

“This is amplified at times of extreme price hikes and declines of crude oil like mid-2008 when oil price surpassed HK$140 a barrel, and currently,” he said.