British schools rush to open new campuses in Greater Bay Area, betting on need for international schooling amid area’s growth

- Ten British schools are expected to open in the GBA by 2022, most of them located in Guangzhou and Shenzhen, bringing the total in the expanded metropolis to 13

- Besides Harrow, the other British schools with GBA plans include Fettes, Kings College, Wimbledon, Lady Eleanor Holles, Shrewsbury and St Bees

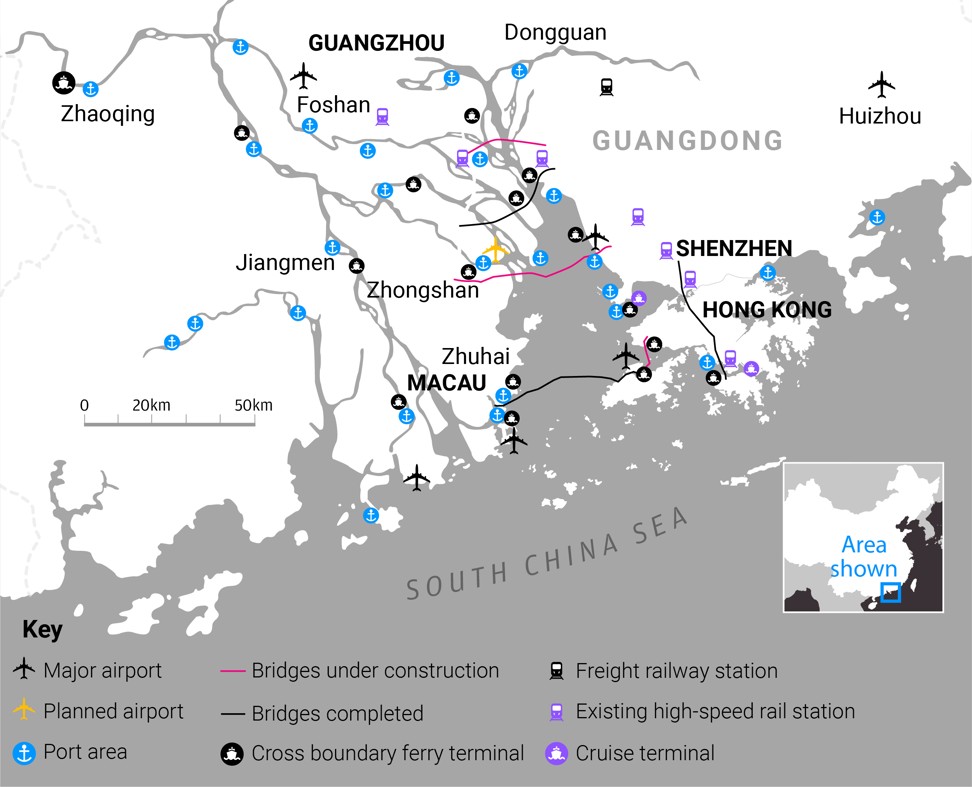

British education institutions are rushing to open campuses in the Greater Bay Area (GBA), betting that the 11 cities around the Pearl River’s delta in southern China will become the growth centre for international schools in their quest for talent and investments.

Ten British schools are expected to open in the GBA by 2022, most of them located in Guangzhou and Shenzhen, bringing the total in the expanded metropolis – with a combined population of 70 million people – to 13, according to data compiled by Venture Education, a Beijing-based consultancy.

Four of eight new branches on the Harrow School’s drawing board will be in Shenzhen and Zhuhai, all ready for enrolment by 2022 when the public school for boys marks its 450th anniversary. Besides Harrow, the other British schools with GBA plans include Fettes, Kings College, Wimbledon, Lady Eleanor Holles, Shrewsbury and St Bees.

“The government is welcoming people to open international schools” in the GBA, said Venture Education’s Senior Partner Julian Fisher during a telephone interview with South China Morning Post. “There is a planned economy here – once [the government] decide a region should open up, it opens up and everyone piles in.”

International schools levy their highest fees in China, the world’s most populous nation and the second-largest economy on Earth, where private institutions and global brands carry a premium for their cache. China is already home to 17 British schools, operating 36 campuses in multiple Chinese cities, offering everything from day classes for children from age 2 to 18 to boarding. Harrow, founded in London in 1572 under a Royal Charter granted by Queen Elizabeth I, already operates campuses in Beijing and Shanghai.

These institutions are turning away from Shanghai, which already has 11 British schools, and the Chinese capital, with four, because it’s becoming harder to get licenses in the two cities, Fisher said. Meanwhile, international schools are being encouraged in the GBA.

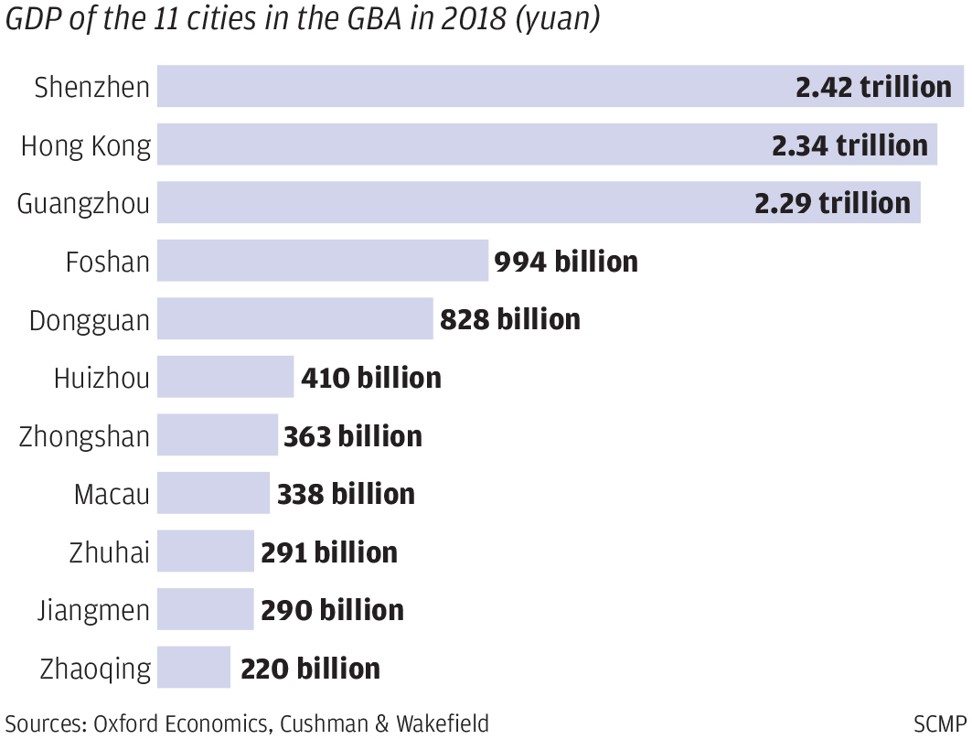

The cluster of nine Guangdong provincial cities, combined with Hong Kong and Macau, accounted for 12 per cent of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017 despite covering less than 1 per cent of the country’s land mass, according to DBS Group Research.

The GBA has a combined economy estimated at US$1.5 trillion, bigger than Spain, which would make it the world’s 13th largest gross domestic product if the area were an independent economic entity. Eighty per cent of the 747 business executives in a KPMG-HSBC survey expect the area’s combined economic growth to surpass the rest of mainland China within the next three years.

Still, the rapid expansion among international schools in the GBA will reach a plateau after 2022, Fisher said. Last year was a difficult year for international schools in China, with 2019 commencements increasing by 5 per cent, slowing from the 12 per cent growth in 2018 and the 11 per cent increase in 2017, according to Venture’s data.

“This has been a challenging year for British independent schools in China, particularly those that are reliant on foreign passport holders only,” Fisher said. “There is definitely a sense in the market that tightening regulations, new laws to comply with and the potential of new laws and regulations around foreign staff, pricing and admissions have slowed growth and presented new challenges.”

“If you want to encourage something in China you create a free-trade zone … once you have got something you’re happy with, you close the barriers,” said Fisher, who is also vice-chairman of the British Chamber of Commerce in China.

A key deterrent was government discussions around a potential cap to admission fees, which was “scary” to schools that predominantly enter China to generate revenue. Most independent schools in the UK are non-profit, even if Dulwich College charges up to £14,782 (US$19,204) per term for full boarding. The four century-old college founded by an Elizabethan actor reported £1 million in 2018 income from its eight campuses in four Chinese cities, according to Financial Times.

Opening in China helps them afford to operate on home soil, and offer discounts to some students.

“It’s about keeping fees at a certain level in England,” said Fisher. “It’s more to be able to offer bursaries [to students in the UK] … rather than generating profit for a certain individual or company.”

A potential cap to admissions, which has not materialised, came alongside an economic slowdown in China.

“The general economic slowdown probably had an impact on schools or partnerships with property companies,” said Fisher. “The market was more cautious from both sides.”

To operate as an international school in China, schools enter into a management contract with local property companies for a fee while still running most operations, or a franchising agreement with an education company who adopt the branding and give roughly 4 to 7 per cent of revenue to the British counterpart. In some cases, UK schools will enter into a joint venture.

Studies are divided into those for foreign passport holders, who learn from an overseas curriculum, or those for mainland Chinese who use a local curriculum.

Fisher said he expects the market to consolidate as time goes on, with less cash being thrown at new international schools compared to the past as the market becomes more tightly regulated. But the wealth and size of the Chinese market, which also places huge emphasis on education, means opening in the country still remains attractive.

“Schools are still a good investment,” said Fisher. “[Investment is] not stopping, it’s just the market is becoming savvier and a little bit less reckless. Ten years ago everything in China was a suitcase of cash, that has changed. It’s a bit more methodical.”

This article was curated by Young Post. Better Life is the ultimate resource for enhancing your personal and professional life.