What has China’s public healthcare system learned from the twin coronavirus outbreaks of Sars and Covid-19?

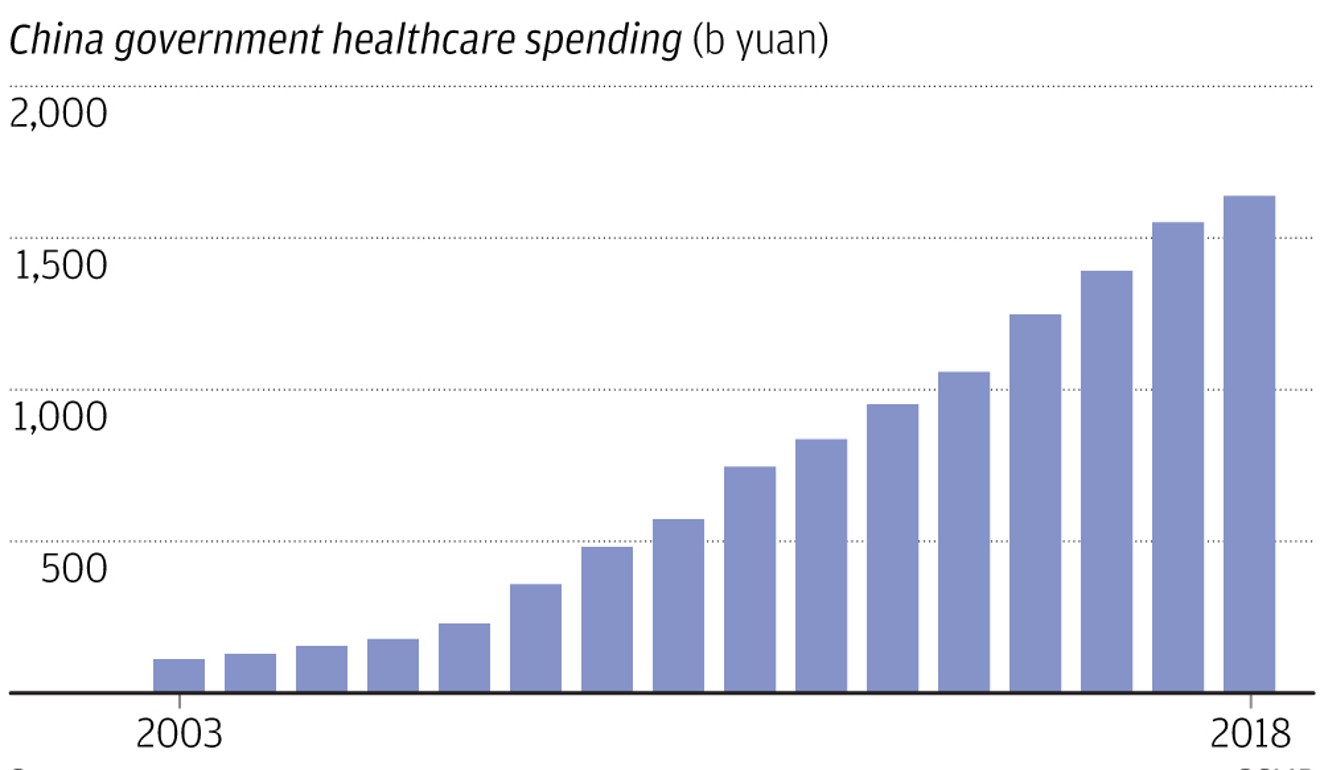

- China’s public-sector expenditure on health care increased almost 14-fold between the Sars outbreak in 2003 and the end of 2018

- System is too “hospital-centric,” fragmented and volume-driven, according to a joint report by the World Health Organisation and World Bank

When the first patients came through the emergency ward at Roberta Lipson’s United Family Hospital in the early spring of 2003 with feverish coughs and chest pains, doctors at Beijing’s biggest privately run hospital had little clue on how to deal with the mystery disease spreading through the Chinese capital.

Befuddled, doctors reached out to the Chinese authorities, as well as the US Centre for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) for help. Based on their advice, the hospital did its best to give patients comfort while the medical world looked for answers. Officialdom eventually named the disease the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) to distinguish it from other types of respiratory tract infections.

“Many of us worked around the clock, upgrading our systems to keep up with the evolving situation and find ways to keep our patients safe,” said United Family Hospital’s chief executive officer Lipson in an interview with South China Morning Post. The disease, caused by a coronavirus, spread to 17 regions and countries, afflicting 8,098 people with a death toll of 774.

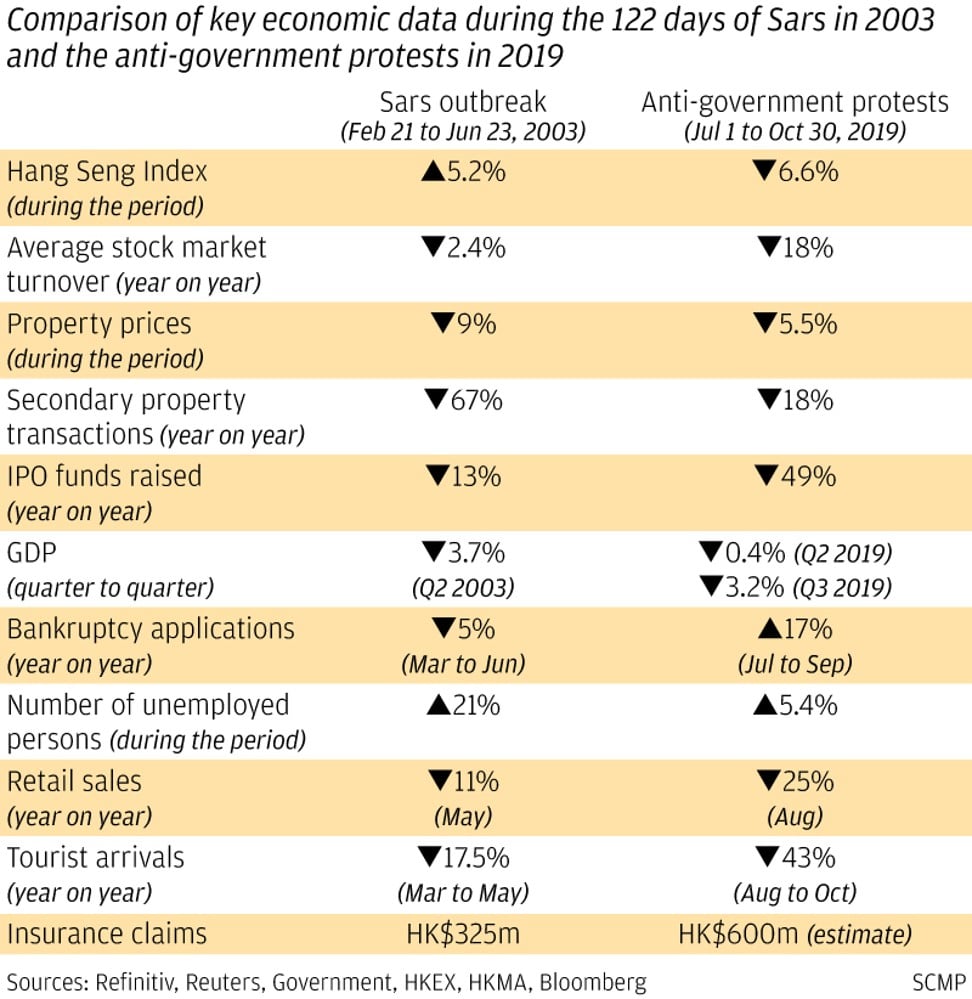

Seventeen years later in 2020, China is again the epicentre of a global coronavirus epidemic, with almost 60 per cent of the world’s 131,627 confirmed cases of Covid-19 at last count. As the slowing economy struggles to maintain the current growth level in health spending, how China proceeds with the next phase of the country’s health care reforms will command the world’s attention, especially for investors looking for opportunities in a market that is expected to grow to 16 trillion yuan (US$2.3 trillion) by 2030.

“Sars was a wake-up call to the government and the public in terms of [having] a system for prevention, and in [raising] public health awareness,” said Lipson, adding that the result was a big improvement in public hospitals, and a lot more transparency in public health data. “In the case of Covid-19, the government has given us excellent guidance, informed us what to do from the very beginning.”

The outbreak of Covid-19 has been a show case of what China learned from Sars. After an initial period of denial, the government moved quickly to quarantine an estimated 50 million people to contain the pathogen’s spread. No expenses were spared to build care facilities, famously completing a 1,000-bed hospital in 10 days.

Record aside, the outbreak also exposed the shortcomings of capacity and capability in China’s health care system, such as limited inpatient capacity of the top-tier hospitals, insufficient capacity to diagnose and treat severe cases, and the imperfect reporting system.

The time is ripe for Beijing’s authorities to galvanise resources and initiate some much-needed reforms to the health care system, but it could be costly.

“I witnessed a big improvement in the past 40 years, but there is still a long way to go,” said Lipson, who first arrived in Beijing in 1979, and formed a medical equipment trading firm Chindex before the establishment of United Family Hospital, now one of the largest private health care service providers in China.

Lipson’s experience traces the arc of modern health care in China. She would not be unfamiliar with the army of “barefoot doctors” – farmers, folk healers and secondary school leavers – who dispensed remedies, procedures and treatments usually with the barest minimum in medical training to the sick and the elderly in the rural countryside during the 1960s.

Much has changed, as an explosive growth in the economy after China’s World Trade Organisation membership flushed the government’s coffers with tax receipts, allowing public-sector expenditure on health care to increase almost 14-fold between the Sars outbreak in 2003 and 2018.

The government was also able to afford universal health care insurance for citizens, a creed for the ruling Communist Party even as it gradually replaces cradle-to-grave welfare and jobs under communism with privatised systems in a market economy. A six-year, 850 billion yuan programme in 2009 ultimately provided almost 100 per cent health insurance to citizens, a feat that was championed by the WHO’s March 2019 report Healthy China: Deepening Health Reform in China released with the World Bank.

Benefits have been gradually expanded, use of health services has increased, and out-of-pocket spending on health – a major cause of impoverishment for low-income populations – has fallen. The average life expectancy at birth today is 77 years in China as of 2018, an increase of 34 years since 1960.

Wealthier nations took twice that long to achieve China’s milestones in public health care, according to the WHO-World Bank report.

Still, the report found that China’s health care system was too “hospital-centric, fragmented, and volume driven.” Cost-inducing provider incentives and a lack of attention to quality were also cited as concerns.

Instead of going to a general practitioner’s clinic, patients would seek specialist care at hospitals even for the common cold, stomach ache or headache, where fevers are invariably treated with intravenous medication. Hospitals share the load disproportionately, with 8 per cent of the system caring for more than half of the entire country’s patients.

China does not have enough doctors, with 1.8 physician – both general practitioners and specialists – for every 1,000 people. That is lower than 2.4 in the US, 2.8 in the UK, 2.4 in Japan and 2.3 in Singapore, according to the World Bank.

Even the training for medical doctors is distributed unevenly to the detriment of the primary care system, the first line of defence for illnesses and injury. China has 2.2 general practitioners (GPs) for every 10,000 people, according to 2018 data. That compares with 12 family doctors for every 10,000 Americans. As a result, specialists at Chinese hospitals are often underpaid and overladen with general practise, where 12-hour days are the norm.

“In China, there is a lack of community-based primary care coverage due to the historical hospital-based legacy,” said Helen Chen, head of L.E.K. Consulting’s China biopharmaceuticals and life sciences practise, referring to the shortage of GPs in local communities, where services are largely provided by specialists in hospitals.

“The government is trying to change this by requiring doctors at large hospitals to rotate through smaller ones and clinics, to help educate rural doctors and spread the health care resources more evenly,” said Chen. “The government is also encouraging patients to go to clinics rather than hospitals for basic care.”

As new Covid-19 infections begin to taper off in China, and the nation’s factories and workshops return to work, the government will have to shift its strategic focus to a longer-term problem that bedevils the health care system: the litany of non-communicable lifestyle diseases such as cancer and diabetes that afflict one of Asia’s fastest ageing populations.

China’s expenditure burden will only increase, even without the Covid-19 outbreak, the WHO-World Bank joint report said, with annual health care spending outpacing revenue by 2.9 percentage points between 2030 and 2035.

That creates opportunities for the private enterprises to fulfil the nation’s needs in disease prevention, diagnosis and treatment. One such investor is New Frontier, co-founded by Carl Wu and Hong Kong’s former Financial Secretary Antony Leung Kam-chung.

“We are building up core health care, senior/rehabilitation care, and clinical services in China as the country is expected to accelerate its shift from low-quality to high quality providers” in health care, said Wu. New Frontier has invested nearly US$2 billion in China, including the US$1.4 billion purchase of United Family from Lipson’s company.

The Chinese government had laid out plans to cut the out-of-pocket payments to 25 per cent by 2030, from 30 per cent of the 2016 total medical expenditure, according to The Healthy China 2030 health care blueprint. The government will also strengthen primary care services, and encouraging the development of commercial health insurance.

Opportunities also abound in the establishment of an efficient, AI-augmented process to produce vaccines for known pathogens to quickly respond to infectious diseases. Big data analysis has gained traction in China amid the coronavirus outbreak.

Authorities in the Zhejiang provincial capital of Hangzhou – home of Alibaba Group Holding, Asia’s most valuable company and owner of the South China Morning Post – launched QR codes on February 12 for use as digital health certificates via the ubiquitous WeChat and Alipay platforms. More than 200 cities have launched their own digital certificates as of February 25. Alibaba’s DingTalk smartphone applications for enterprises gets 150 million check-ins every day, generating useful data for monitoring the disease’s spread.

“There will be a holistic health care system empowered by technology from early prevention and diagnosis to treatment,” dubbed HealthTech, said Jens Ewert, Deloitte China’s Life Sciences & Health Care Industry Leader.

“In the past few years, a lot of capital had been attracted to the R&D, pharmaceutical and biotech companies as they were getting a larger portion of the value in the chain and many of them focus on oncology products and high value treatment,” he said. “Going forward, the [Covid-19] crisis has shown that health care providers, medical staff and services need to be more attractive to catch.”

Lipson famously founded Beijing United after accompanying a pregnant friend to a Chinese obstetrics facility during the early 1990s “left much to be desired,” according to a post on United Family’s website.

“A few months after the Sars outbreak, we saw a 300-per cent jump in the sale of commercial health insurance, as many Chinese chose private hospitals over state institutions, which created opportunities for our business,” she said. “If I ever fall sick again, I will go to United Family Hospital.”

Additional reporting by Eric Ng

Purchase the China AI Report 2020 brought to you by SCMP Research and enjoy a 20% discount (original price US$400). This 60-page all new intelligence report gives you first-hand insights and analysis into the latest industry developments and intelligence about China AI. Get exclusive access to our webinars for continuous learning, and interact with China AI executives in live Q&A. Offer valid until 31 March 2020.