Boom to busting and back again: the ‘BRICs’ highlight how catchy acronyms don’t form the basis of a solid trading strategy

Renewed appetite for emerging-market assets should not be conflated with a revival of the BRICs trade

On Monday, Argentina, which has defaulted on its sovereign debt eight times, most recently in 2014, issued a landmark 100-year US dollar-denominated bond in a sign of the fierce appetite among international investors for higher-yielding emerging-market assets.

If even Argentina, which only lifted capital controls two years ago and is still assigned a “junk” credit rating despite having launched ambitious reforms under a new president, is able to issue a “century bond”, then it is not surprising that investors are once again ploughing money into the quartet of Brazil, Russia India and China, otherwise known as the BRICs.

The BRIC thesis itself was developed by Jim O’Neill, a former chief economist at Goldman Sachs, in 2001 to describe the growing economic clout of some of the largest emerging markets. South Africa was later added making it BRICS.

But as a trading strategy, the original four appear have lost their appeal over the past several years as recession-plagued Brazil and Russia were stripped of their investment-grade credit ratings, India suffered a sharp sell-off during the “taper tantrum” in 2013 and concerns about China’s economy and policy regime intensified in 2015.

According to Bloomberg, the largest BRIC exchange-traded fund, a popular investment product that tracks an index or market, plummeted 40 per cent between the end of 2012 and the beginning of 2016.

Even Goldman Sachs had to close its BRIC fund at the end of 2015 after the vehicle’s assets tumbled from more than US$800 million in 2010 to US$100 million.

Yet suddenly BRICs trade is proving more popular these days.

After suffering capital outflows for much of last year, the original BRICs are enjoying a surge in inflows this year, with fund flows to the four countries reaching their highest level since July 2015, according to Bloomberg.

Foreign investors’ holdings of Chinese equities have more than doubled since 2013 to US$635 billion, while non-resident purchases of Russian domestic government debt have reached their highest level in four years, according to data from JPMorgan.

Indeed, more positive narratives have emerged for each of the BRICs.

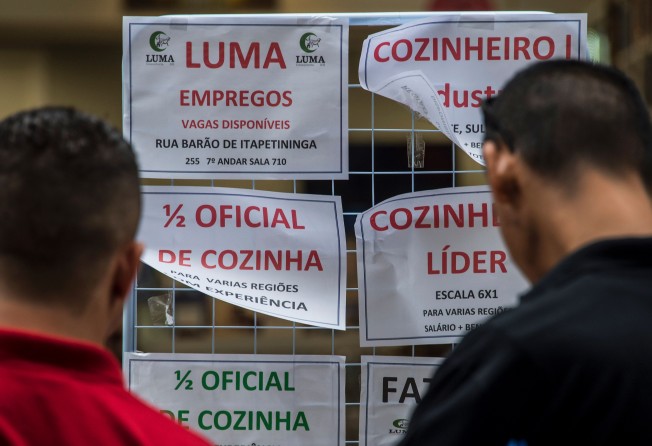

In the case of Brazil, the impeachment of former president Dilma Rousseff last year and her replacement by the reform-minded Michel Temer have improved the prospects for the country’s creaking public finances, with a new cap on real increases in spending and plans to overhaul the pension system.

Russia, meanwhile, has exited a deep recession and just this week managed to issue US$3 billion of sovereign debt to mainly US-based investors despite facing Western sanctions over the crisis in Ukraine.

Sentiment towards India has improved dramatically since Narendra Modi’s emphatic victory in the country’s 2014 parliamentary elections. A raft of reforms, including the introduction of a nationwide goods and services tax, has contributed to a surge in inflows into India’s local bond market.

As for China, foreign investors have taken comfort from the resilience of the yuan in the face of significant strain on the country’s equity and debt markets stemming from the clampdown on leveraged investment.

Sentiment towards China was given a boost on Wednesday following MSCI’s decision to begin including stocks from its A-share market, the world’s second-largest by capitalisation, in its global indices.

The BRICS concept was a gimmick from the start designed to draw attention (and increase investors’ exposure) to developing economies

Yet renewed appetite for emerging-market assets should not be conflated with a revival of the BRIC’s trade.

The BRIC concept was a gimmick from the start designed to draw attention (and increase investors’ exposure) to developing economies.

Other popular acronyms for emerging markets, such as MINT and CIVETS (which include nations as diverse as Colombia and Turkey), were also over-hyped and showed the fallacy of trading emerging-market regions as homogenous entities.

Differentiation has become the watchword in emerging markets. Moreover, some of the factors that prompted investors to pull money out of the BRICs are still present.

Oil prices have just entered their first bear market since August because of mounting concerns about the oil cartel Opec’s ability to ease a supply glut. This is particularly bad news for Russia, the world’s second-largest oil exporter and largest producer.

Politics is also a key vulnerability. In Brazil, Temer’s presidency is hanging by a thread as a rapidly escalating corruption scandal threatens to unseat him.

As for China, while sentiment among foreign investors is holding up well, concerns about policymakers’ ability to manage the surge in the country’s indebtedness are growing, as the decision by Moody’s Investors Service last month to cut China’s credit rating clearly attests.

Catchy labels and acronyms may be part of good marketing but they should not form the basis of a trading strategy. Investors in BRIC funds should know this by now.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory