A universal basic income won’t solve the problem of jobs, or the lack of them, in the coming ‘post work’ world

The idea of a guaranteed wage paid to all by the state is detracting from the need to reconsider our approach to work in the age of artificial intelligence

As a working class kid in the UK in the 1960s, the unrelenting financial struggle meant that every school or university holiday, I knuckled down to summer jobs, winter jobs – any jobs – to make ends meet. I watched in perpetual jealousy as lucky middle class kids flew off for winter skiing holidays, or to laze on Mediterranean beaches.

Jealousy aside, by the time I left for university, I had worked on farms, in petrol stations, in can-making and food-freezing factories, in waste recycling yards, and – every Christmas – at the post office delivering mail. Every day through my teenage years started at 5.30am, biking across the town’s suburbs as a newspaper delivery boy. I funded university study by spending summers teaching English language to foreign students, and working behind a bar.

Apart from the cash these different jobs provided, they had a second, even bigger value: they introduced me to the thousands of lifetime jobs out there that I never, under any circumstances, wanted to be forced to do. It did not necessarily show me what I truly wanted to do, but it certainly showed me what futures I wanted to avoid at all costs. It warned me of the drudgery embedded in so many jobs that fill people’s lives over their lifetimes.

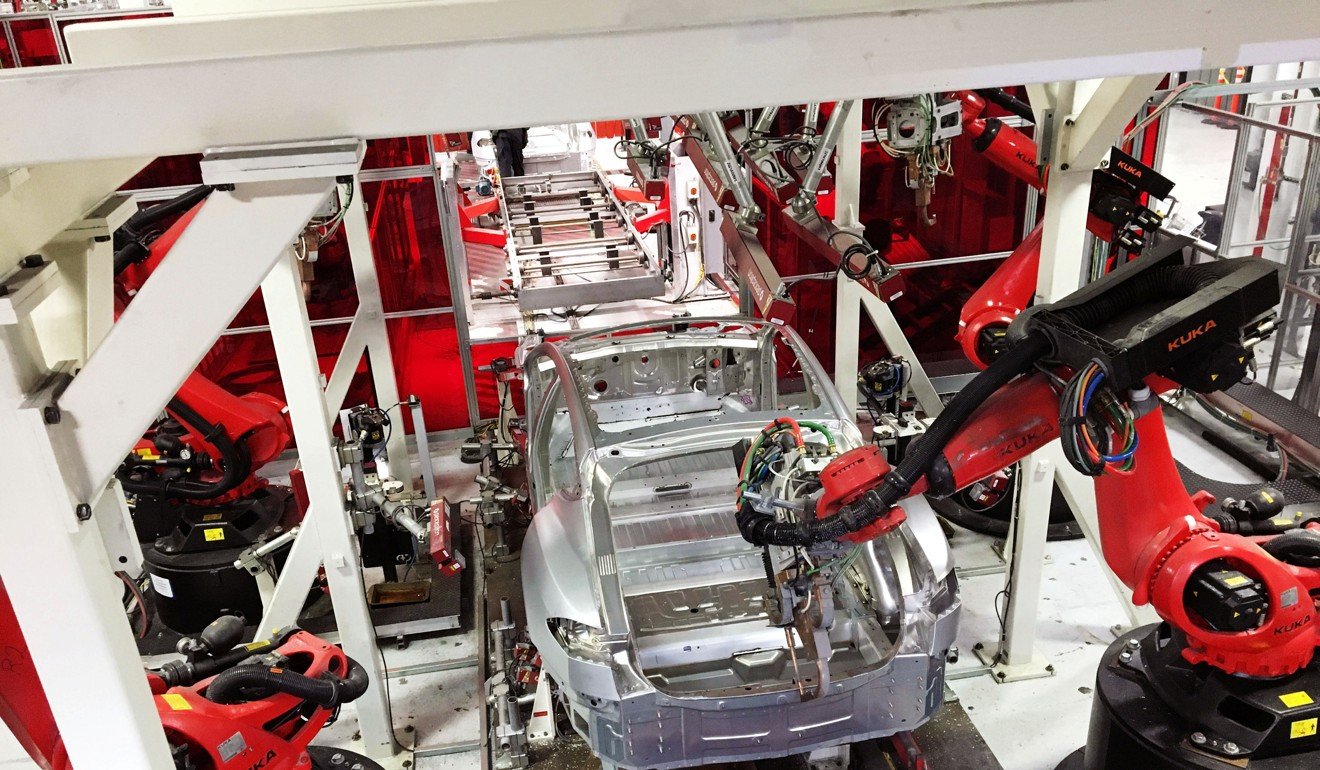

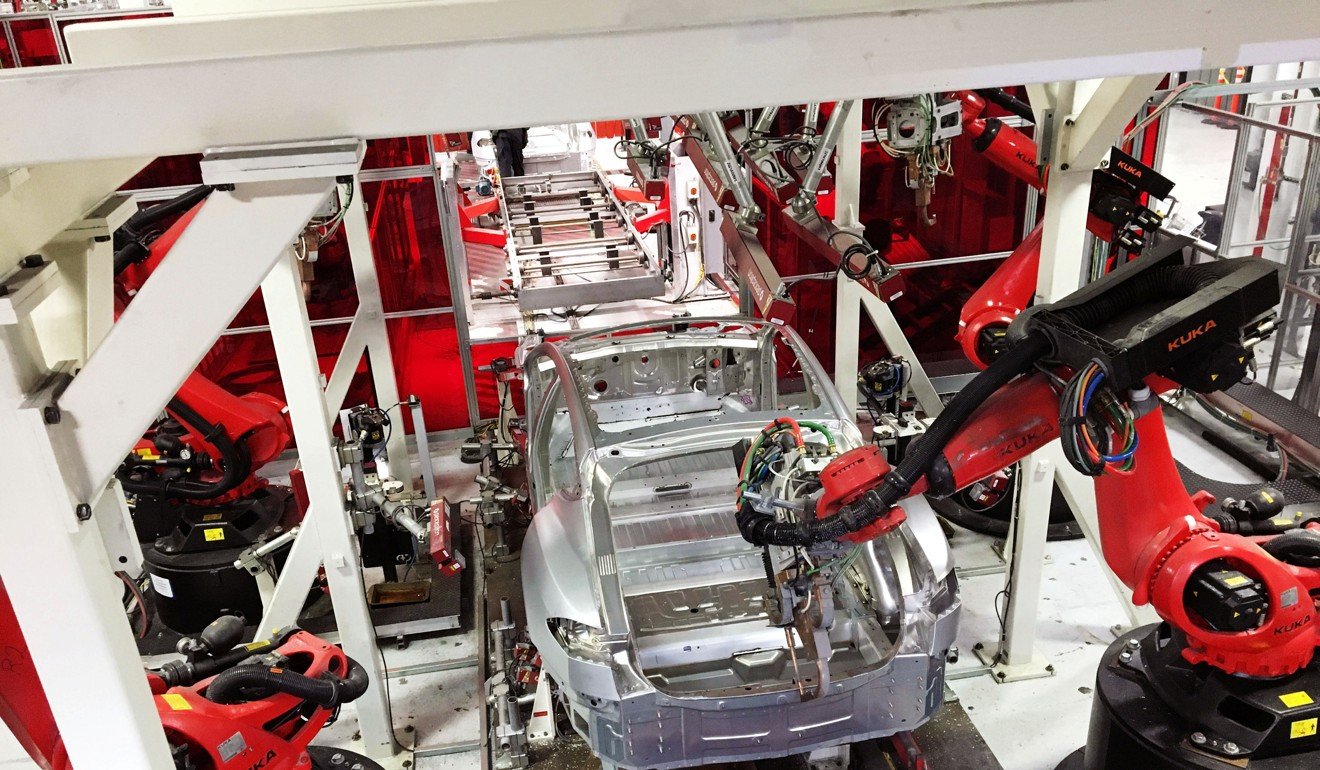

Now, half a century later, I see thousands of youngsters who are fretting about how artificial intelligence and robots are going to destroy jobs, and who are biting their nails over whether they will have the skills needed to fill the jobs that are left.

The good news is that many of the jobs being destroyed are exactly those drudge-laden jobs I experienced – and came to hate – in my teenage years. The bad news is that our governments, businesses and educators are only now beginning to address the biggest challenge that has faced the world of work in at least a century.

Even worse, while at last there is rising concern over the digital challenge to “future jobs”, many in government, business and education seem reluctant to address an equally large, and equally certain challenge: demographic changes that are filling the world with older people.

Structurally today, in most countries, attitudes towards old age and rules on retirement mean these older people are seen as a liability, and are being barred from providing part of the solution to the “future jobs” challenge. Anxiety about a shortage of jobs for our young means governments and employers are reluctant to enable the fast-growing number of “healthy old” to stay in work.

But let me leave this issue to next Saturday’s column, and focus instead on two natural but eccentric and counterproductive responses to the digital challenge: the “post work” movement that is questioning why we should remain tied to what US anthropologist David Graeber calls a life of “bullshit jobs”; and the idea of a universal basic income (UBI) as some kind of solution to the crisis.

The emergence of such ideas, which I remain firmly convinced are utopian and unhelpful, is perhaps inevitable, given the gravity of the “future jobs” challenge, the political backlash to widening inequality, and the fundamental drudgery of so many jobs, which I remember only too clearly.

The case for building a “post-work” world was well explored a month ago by Andy Beckett, a journalist with the UK’s Guardian newspaper. He reminds us that the relentless grinding world of work as many know it today was “invented” barely a century and a half ago, basically the product of industrial capitalism. This “post-work” world rejects the “serfdom” created by industrial machinery, and glimpses back sentimentally to the “freedom of the medieval artisan”: “Life with much less work, or no work at all, would be calmer, more equal, more communal, more pleasurable, more thoughtful, more politically engaged, more fulfilled.”

The movement, driven mainly in the UK, the US and some European countries, clearly has roots back in Karl Marx’s vision of the freedoms in a communist society where workers could “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner”. One also sees roots in the socialist William Morris’ 1880s vision of future factories surrounded by gardens in which employees worked just four hours a day, and in John Maynard Keynes’ “age of leisure and abundance” that would arise as technology advanced.

Utopian and naive as such thinking may be, one can understand how decades of income stagnation and dwindling income and job security for so many working people translates into such thoughts. But they have been given traction by a quite earnest and detailed debate over the possible introduction of a universal basic income (UBI), by which, regardless of whether you have formal work, everyone would receive a monthly income from the state.

The idea is apparently receiving serious attention from the UK’s Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, who has enough utopian unreality in his veins to press it forward if he ever gets a chance in power.

Meanwhile, I remain persuaded by Ian Goldin, professor of globalisation and development at Oxford University, that there at least five reasons UBI is a red herring:

First, that it is financially irresponsible and would lead to budget deficits, higher taxes and diversion of resources from health and education;

Second that it would increase inequality, not reduce it, by sharing available resources across the entire electorate regardless of need, rather than focusing them on people in need;

Third, that it would destroy social cohesion by undermining the value of activity in the workplace where individuals “gain not only income, but meaning, status, skills, networks and friendships”;

Fourth, UBI would undermine incentives to participate in the creation of appropriate safety nets: “Safety nets should be a lifeline towards meaningful work and participation in society, not towards a lifetime of dependence”;

Finally, that UBI would postpone, and distract attention from, the real challenge, which is to develop strategies to equip us with the skills needed to fill the “future jobs” that our economies will need in coming decades.

Professor Goldin concludes: “There must be more part-time work, shorter weeks, and rewards for home work, creative industries and social and individual care. Forget about UBI. To reverse rising inequality and social dislocation we need to radically change the way we think about income and work.”

That will be my challenge in next Saturday’s Inside Out.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view