Bravo to Cambridge University for its U-turn on China’s censors

‘The incident represents the dangers of China’s bid for internet sovereignty and cyber imperialism’

When facts and truth become banal, where “fake news” is like daily wallpaper, then censorship simply becomes an easily justifiable business and editorial decision.

Whether it is social media that we’ve so slavishly been devoted to, or in China where it is a reality of gaining market access, the conflict over the importance of truth has necessarily become more amplified.

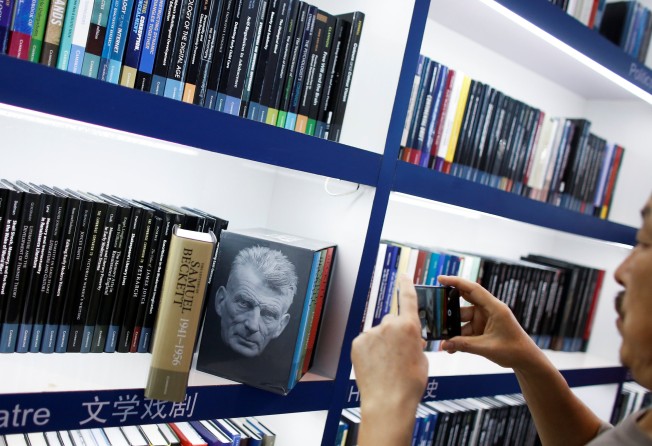

The publishing arm of the University of Cambridge has reversed its earlier decision to block access to more than 300 articles in China, after it was accused of folding to Beijing’s pressure. The incident represents the dangers of China’s bid for internet sovereignty and cyber imperialism.

“It is not the role of a respected global publishing house like CUP to hinder access to the journals it publishes. This puts academic freedom where it belongs, which is before economic considerations,” Tim Pringle, editor of the China Quarterly, the Cambridge University Press’ (CUP) leading China-focused journal said on Monday.

Reconcile this by presuming that Pringle’s first consideration was really profits. Cambridge sells content and subscriptions in China. They may well be threatened with a total loss of access to that market. But that doesn’t make their initial decision any more acceptable. It just confirms that the CUP, and indeed Cambridge University, was probably starting to act more like a business than as a traditional academic institution. This time, the academics resisted.

CUP did the right thing, although it may face complete censorship in China. As always, some would argue that partial access to ideas and self-censorship is better than suffering a complete ban from China.

That view is wrong. Censored ideas have little, to no value, at best. A self-respecting rejection of it sends a clear message to the censor and readers alike.

China could block access to all of CUP publications - as it does with many other sites. Was freedom of expression, and ideas helped by this stance?

Or in retrospect, would CUP have been smarter to block a group of sensitive articles in order to distribute the majority of its content to a Chinese audience? It’s not a clear business decision.

China’s censorship increasingly reverberates outside the country’s borders because it is an extension and export of its economic power. To be sure, Western technology companies also engage in censorship, except the Chinese government is more blunt in its intentions, and more robust in its execution.

Censorship also occurs in the US, and its most dangerous manifestation lies not in Washington, but in Silicon Valley. Accusations are being thrown at Facebook, Google and others about how they censor or “filter” what they define as undesirable, conservative political content.

The people who run the bots and algorithms that manage the news feeds of these technology companies are promoting and distilling a progressive, liberal, viewpoint bias. And they are doing so with little, or no transparency. They are self-regulated and beyond investigation.

The technology that was supposed to free everyone to broadcast unfettered ideas on the internet, without submitting to squads of editors, has been flipped around to allow global corporations to oversee and even squelch free speech.

At the same time, technology allows a concentration of power for governments and corporations to censor all information, all the time.

Labelling this as pro-Beijing, morally ambivalent propaganda is like dismissing all of Donald Trump’s supporters as racist, dumb, uneducated or poor. While there might be elements of truth, it oversimplifies and misses the big picture.It is unhelpful as it fails to visualise the coming conflict.

If you want to do business in China, you have to do so respecting China’s laws. Unfortunately, permitting Western media to spread unfiltered and unfettered Western beliefs, opinions, values and cultural quirks in China is not something the Chinese Communist Party is especially thrilled about.

The outcome of this cyber war is predicated by the lack of conviction on the part of those who are caught in the crossfire.

Yet, this will change as American firms seek US government support in opening up the Chinese market. Ultimately, free speech principles can only be protected by governments, not corporations.

A censorship war can escalate if governments decide to reciprocate. Imagine Cambridge University banning Chinese scholars.

Or if the US government enacts cyber protectionism, and entirely blocks Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent platforms from the US just as Google is blocked from China. The possibilities are endless and treacherous.

The idea of unfettered free trade with regimes who do not respect Western values does not seem to be working according to plan.

Free trade led to cultural convergence in the past, but it has not eventuated with China. Then, on the other hand, the West is toying and acquiescing with technology-enabled censorship. Unlimited free speech is no longer practical in this tech world.

Belief in its ascending power has convinced China that its restoration through a one-party authoritarian state need not surrender to the destined forces of political evolution, which Schopenhauer and Hegel had declared to be irresistible.

Believing themselves to b superior in soul, in strength, in energy, industry and national virtue, China is also seeking its cyber dominion.

Peter Guy is a financial writer and former international banker