Bo Xilai's trial underlines need for cross-examination in court

Jerome A. Cohen says Bo Xilai's feisty questioning of witnesses, and the fact he was unable to cross-examine his wife in court, have awakened the public to the inadequacies of China's criminal justice system

In order to establish a rule of law worthy of the country, China will require leaders endowed with vision, wisdom and boldness. Several decades of economic, social and legal development have increased popular demand for a legal system that is fair, impartial and reasonably free of politics and corruption. What has been lacking is leadership.

I once thought that Bo Xilai, because of the intelligence, openness to the world and charisma that marked his pre-Chongqing career, might become such a leader. If the political opportunism that he displayed in embracing Maoist propaganda and tactics in Chongqing had succeeded in propelling him into high national office, I thought that the same opportunism might then motivate him towards the other direction - to assure himself a role in history by helping to bring due process of law, judicial independence and fair trials to one-fifth of humanity. Bo's high-rolling Maoist gambit failed. Yet history works in strange ways.

Few familiar with Bo's record as Chongqing's Communist Party boss would have predicted that his final contribution to Chinese politics would be to strengthen reformers struggling to lead the country towards the rule of law.

Bo's five years in Chongqing were an unmitigated disaster for criminal justice. With the aid of notorious police chief Wang Lijun , Bo's regime featured unauthorised electronic surveillance, even of central Communist Party leaders; lawless search and seizure of private property; arbitrary detention and arrest of thousands of hapless victims; and hideous torture inflicted not only to coerce frequently false confessions from suspects but also to punish them - sometimes fatally - long before their cases could be formally processed. By intimidating defence lawyers and manipulating both judges and prosecutors, Bo and his minions turned criminal cases into both tragedy and farce, and some of the targets of his famed "strike black" campaign against crime were executed after blatantly unfair appellate as well as trial proceedings.

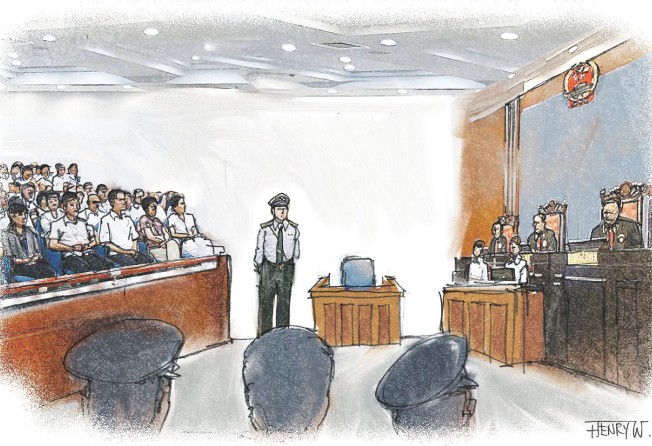

Bo should have been prosecuted for these human rights violations but was not. Yet, in his trial, despite the many limitations imposed by his former party comrades, Bo did more to heighten public awareness of the unfairness of "the socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics" than Mao Zedong's widow, Jiang Qing , did in the largely televised 1980-81 trial of the Gang of Four. Moreover, although media attention has not yet focused on the prospect, Bo, unlike more compliant political offenders, including his wife, Gu Kailai, and Wang Lijun, may insist on his right to appeal against conviction. Under China's procedure law, that would make possible another full trial of most of the case, further challenging party leaders to demonstrate their respect for the rights of an accused to defend himself.

Criminal justice has been the weakest link of China's legal system, which, despite constitutional and legislative protections of the right to defence, has in practice rarely allowed defendants adequate opportunity to question prosecution witnesses and rebut their claims. Although Anglo-American justice has long regarded cross-examination as the greatest instrument ever invented for the discovery of truth, in China, open rejection of government accusations in a truly public trial has usually been deemed unacceptable.

The People's Republic recognised the value of cross-examination by authorising its use when, in 1996, the National People's Congress made major revisions in its original Criminal Procedure Law. This was a potentially exciting development. Unfortunately, it constituted an improvement in principle but not in practice.

Since the new law was not interpreted to require witnesses to appear in court in criminal cases, witnesses continued to give live testimony in fewer than 5 per cent of such cases. Thus, Chinese defendants could rarely take advantage of the new cross-examination opportunity. Prosecutors would simply read into the court record the pre-trial statements obtained from witnesses, who were insulated against the hazards of hostile questioning. Even the best lawyer cannot cross-examine a piece of paper!

When the Criminal Procedure Law was again revised last year, an effort was made to enhance the likelihood that witnesses might come to court, but thus far the new amendments do not seem to be very effective. Indeed, they grant one spouse the right not to testify against the other in or out of court.

This is the background to the pathetic situation that marred the first day of Bo's trial. No witness against him was more crucial than his wife. Bo twice requested that she be summoned to testify in person so that he might question her account. The chief trial judge said he approved the request, which was endorsed by the prosecution, but claimed that Gu refused to accept it.

Yet Gu did choose, or was coerced, to testify against Bo outside of court. What she or party leaders did not want to happen was to expose her testimony to cross-examination. In the hope of making her failure to come to court more palatable, the court introduced a video of part of her testimony that had been read aloud in court the previous day, so that people could at least have a brief view of her untested demeanour.

Bo's subsequent spirited and lengthy interrogation of live witnesses Xu Ming , Wang Lijun and Wang Zhenggang , and his repudiation and ridicule of their testimony, indicated the type of experience Gu had been spared and the extent to which her testimony might have been modified or rebutted on cross- examination. That his questioning of Xu had bolstered Bo's defence was immediately acknowledged by party propaganda officials, who instructed the domestic media not to headline what they called "the 20 questions".

Some of Bo's arguments were unpersuasive and, understandably, his cross-examination skills sometimes appeared modest. Nevertheless, their well-publicised display, even through the constricted lens of the court's increasingly censored microblogging, undoubtedly made a major impact on a public unaccustomed to the adversary system that China has taken steps towards introducing but seldom implemented. This alone justified Xinhua's boast that the case constitutes "a landmark in the history of Chinese jurisprudence".

Jerome A. Cohen is professor and co-director of the US-Asia Law Institute at New York University School of Law and adjunct senior fellow for Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations. See also www.usasialaw.org