What housing crisis in Hong Kong?

Ian Brownlee says a look at the facts reveals that only a small percentage of Hongkongers live in very poor conditions. For the vast majority, quality of life issues take priority

There is no doubt that a lack of land sales by the administration under former chief executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen resulted in a housing shortage. The current administration has made housing its overriding priority, calling it a crisis. Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying says it "is the major concern of everyone in Hong Kong" and has called on the public, district councillors and green groups to support his proposals.

But is there really a crisis? The facts tend to show otherwise. Perhaps only a few see housing as a priority; for many, other things are more important. More housing is really important to a small group of people living in very poor conditions, but not to others.

There are usually two criteria applied to housing - affordability and quality. Affordability, to rent or buy, is an international problem facing cities such as London, Vancouver and Sydney. In many cities, the lack of subsidised housing is part of the problem, as those on lower incomes have no alternative. In "third world" cities, the problems are compounded by widespread poverty, a lack of public resources, large squatter or slum areas, and many homeless. Compared with these, Hong Kong is not in crisis.

The government's Long Term Housing Strategy, released in December, considers all those living in subsidised housing to be adequately housed at affordable rates, and they account for 45 per cent of all people in Hong Kong. A very large proportion, therefore, have no problems.

For private housing, which meets the remaining 55 per cent of need, the strategy defines those that are inadequately housed. Yet, the definition confuses the problem, as it also says that not all people in inadequate housing are necessarily inadequately housed. The strategy takes a conservative approach, and includes all defined households.

The first group comprises the 15,700 households living in temporary structures, huts or rooftop structures. Temporary structures in Hong Kong are buildings made of wood and with metal roofs, or those not approved by regulators. Buildings made of such materials would be considered adequate housing in places such as Canada and New Zealand, where they make up a large part of the housing stock. I know of one household who left their Happy Valley penthouse to move to a temporary structure with a full sea view at Shek O, full amenities and all modern conveniences. They are not "inadequately housed", but others are.

The second group is the 3,000 households who live in commercial or industrial buildings. These buildings are usually permanent and provide solid, safe accommodation, but the system does not allow them to be approved for residential use. If fire safety requirements could be met, there is no real reason why they could not be converted to "loft-style" apartments here, as in many other cities. There are many "unauthorised" high-end loft apartments in our industrial and commercial buildings which provide good accommodation. People there are not inadequately housed.

The third group is the 11,300 households who share with other households, in rooms, cubicles, and the like. In many other places, such sharing is an accepted form of housing for people at a certain stage of their lives - particularly for young people. Sharing is one way of overcoming problems of affordability. Yet, the strategy lists these as inadequately housed.

Fourth are the 75,600 households who live in subdivided units. There are obviously situations in which the physical conditions in these units are not acceptable but, again, they meet a social need that is not met by subsidised housing. There are also good standard subdivided flats that accommodate people who prefer this form of affordable housing to other options. But under the strategy, all are listed as inadequately housed.

This makes a total of only 105,600 "inadequately housed" households but, in reality, many are living in acceptable conditions. The strategy is overstating the problem. It also states that all the other households in private accommodation are adequately housed.

Last year, there were 2,437,000 households in Hong Kong. If fewer than 105,600 (4.3 per cent) are inadequately housed, then 95.7 per cent are adequately housed. Hong Kong does not have a housing crisis.

Affordability is very loosely defined in the strategy because "different societies have different views". Affordability is "to enable people to meet their housing needs in accordance with their means". That is not really very helpful, as there is no indicator as to when "affordable" housing will be achieved, if it ever can be.

What about the huge demand for public housing and the long waiting times? These are a creation of the poor definition of eligibility. Too many people are eligible, and it is creating false hope that large numbers in private housing will eventually get public housing when they won't. There will never be enough public housing to meet those currently eligible to apply.

How can a Home Ownership Scheme application be 60 times oversubscribed and considered reasonable when 59 out of 60 people will not get a flat? Public housing eligibility criteria should be redefined to identify only those with a real need - such as the 105,600 inadequately housed households for a start. Why not set a different target - to provide subsidised housing for half of all households in Hong Kong and redefine the criteria to cater for the neediest?

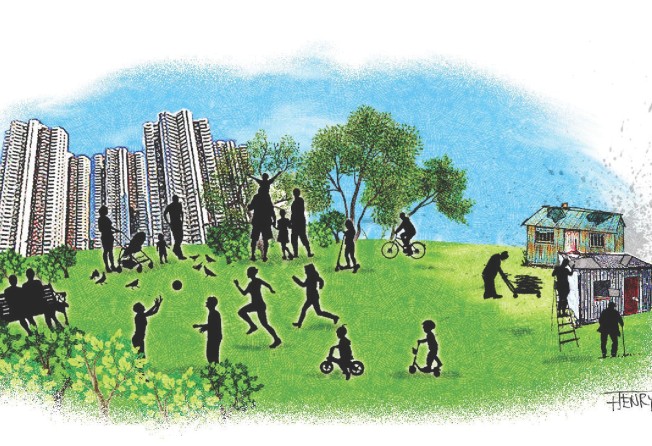

There is a need to provide a continuous supply of new housing, both public and private, but there is no "crisis" and therefore no reason to recklessly reduce the sustainability of our city by rezoning sports fields, community and social support sites, and our green belts for housing. This will only create much more significant problems in the future regarding the quality of life Hongkongers strive for. Academics are warning of an increased urban heat island effect, and they should not be ignored.

The government is asking people to get behind its drive to provide housing, as this is the basis for many problems in the community. Fortunately, 95 per cent don't have a housing problem and are more concerned about quality of life issues than housing for others. They, therefore, have legitimate reasons for objecting to their parks and green areas being removed, as the quality of their lives and of future generations is more important to them than a poorly substantiated housing crisis. Proper systematic planning of new towns is the way this continuous supply of new housing should be addressed.

Ian Brownlee is managing director of Masterplan Ltd, Planning Consultants