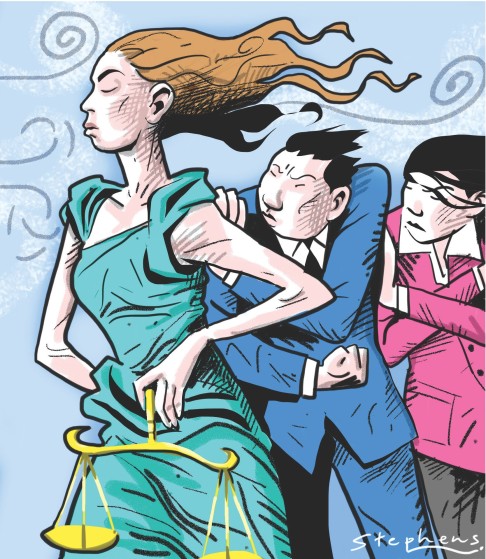

How strong institutions help Hong Kong safeguard its autonomy

Johnny Mok says Hong Kong must work harder at strengthening its institutions to protect its autonomy

The former Legislative Council building was formally returned to the judiciary last week. Anticipating this event at the opening of the legal year in 2012, the chief justice reminded the audience that this historic building officially opened a century ago as Hong Kong's courts of justice; and that, in 1912, these words were spoken by then governor Sir Frederick Lugard that have proven true to date: "[O]ur courts of justice shall always surpass all other structures in durability, firm set on their foundations and built four-square to all the winds that blow, as an outward symbol perhaps of the Justice which shall stand firm though the skies fall…"

At the opening of this venue as the new Court of Final Appeal building last Friday, Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma Tao-li said: "This building is the symbol of the rule of law in Hong Kong and this institution remains as strong as it has ever been in our community."

These are reassuring words; after all, the rule of law constitutes a cornerstone of Hong Kong's high degree of autonomy.

It is no exaggeration to say that the strength of the rule of law has vastly contributed to the maintenance of the high degree of autonomy in Hong Kong

This autonomy ensures that we in Hong Kong will enjoy the life and lifestyle we have been used to for at least a period of 50 years. Under the "one country, two systems" formula, this autonomy also comes with all the economic advantages of being connected to the mainland.

The content of our high degree of autonomy is contained in the Basic Law - most importantly, in the provisions defining the institutional structure of government - the office of the chief executive, the executive authorities, the legislature and the judiciary - mandating each to function according to the principles set out in our mini-constitution.

The more effective those institutions are in carrying out their duties, the more dynamic will they function as the engines of our autonomy. In a lecture given earlier this year, the chief justice measured the rule of law by reference to six objective indicators: transparency, reasoned judgments, protection of human rights, independent processes for the appointment and removal of judges, access to justice, and views of the court users.

In particular, he said, the "existence of the rule of law and its legitimacy in any community is entirely dependent on the respect in that community for the concept as a core value of society". If, by those measures, the rule of law exists, "it is undoubtedly a strength and becomes an institution which has a long-term future".

It is no exaggeration to say that the strength of the rule of law (which encompasses the independence of the judiciary) has vastly contributed to the maintenance of the high degree of autonomy in Hong Kong.

At the same time, to the extent that Hong Kong's institutions are paralysed, autonomy is weakened and becomes vulnerable, leaving open areas of unfulfilled needs and promises intended under the Basic Law to be met by such institutions.

Indeed, systemic institutional failures could shake our autonomy as a special administrative region. A good example is the SAR's inability to enact local legislation in accordance with Article 23 of the Basic Law for almost two decades since 1997. This had led some to propose that national laws could be extended to Hong Kong to fill the gap. I do not consider this a good solution; nor is it likely to be adopted. But the example serves to illustrate how systemic failure could potentially undermine autonomy.

There were other signs of systemic paralysis, such as the failure to effect constitutional reform to usher in universal suffrage, the serious and repeated delays in passing legislation, the government's difficulties in trying to implement its social and other policies, and an increasing tendency to resort to the courts to ventilate political conflicts. Law professor Johannes Chan Man-mun said this trend of "judicialisation", whereby the courts are used to pursue social and political agendas, came about when both Legco and the executive government became crippled or ineffective.

The next test of our systemic health will soon come, as Hong Kong must decide on a timely and effective system for the co-location of immigration and customs facilities with mainland China at our new terminus for the express rail link.

It is a great irony that those who undermine our institutions in this way believe that it would bring about a higher degree of autonomy for Hong Kong, because they may, in fact, achieve the opposite. Their efforts compromise the very foundation of our autonomy, and chip away at the advantages with which the city has been endowed.

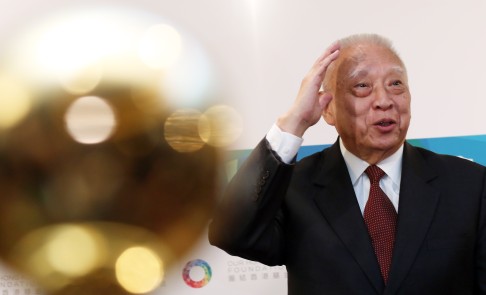

Happily, there are signs that steps are being taken in different quarters to seek new and creative solutions. The following are only some of the examples: former legislator Ronny Tong Ka-wah has set up the Path of Democracy group to find a "third path" for political reform; Tung Chee-hwa, the city's first chief executive, has launched Our Hong Kong Foundation, which is committed to fostering social consensus on critical issues confronting Hong Kong; the central government has begun engaging some pan-democratic politicians in constructive dialogue; Legco president Jasper Tsang Yok-sing is contemplating the formation of a new think tank to tackle Hong Kong's political issues; pan-democratic lawmakers have mobilised a four-member group to coordinate news within the camp about talks with Beijing, to demonstrate that they embrace dialogue.

Such efforts are laudable and should be encouraged. The ultimate goal is to restore to Hong Kong the great vision that, under the umbrella of our one country, we can and do continue to function autonomously, and prosper in so doing.

The august building which now houses the Court of Final Appeal is, to me, more than a timely reminder of the importance of the rule of law in Hong Kong; it also bears testimony to this fact - that the rule of law has been developing here for much more than a century and has now firmly taken root, whereas the other institutions of the Hong Kong SAR are still in their infancy.

How we grow those institutions is a choice that we, as a community, must make together. While it may be that some degree of political polarisation is inherent in the concept of "one country, two systems", and that some misunderstandings between the two systems are inevitable, it is incumbent upon all of us to try to rise above the present conflicts, knowing that, at the end of the day, it is the combined strengths of all our key institutions that will guarantee our city's autonomy, up to 2047 and beyond.

Johnny Mok is a senior counsel and member of the Basic Law Committee