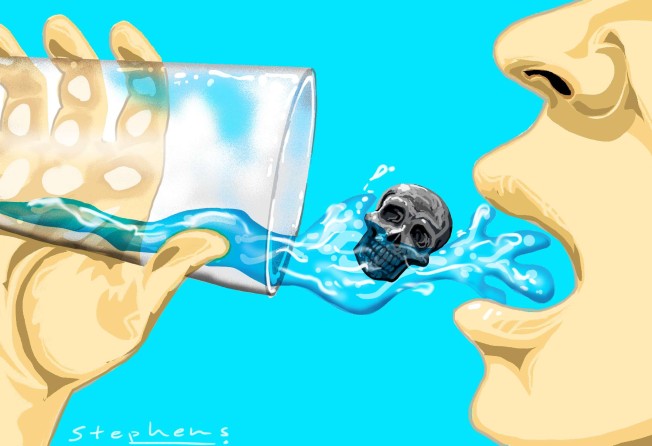

Why there’s no safe amount of lead in tap water in Hong Kong, or anywhere

James Nickum says the WHO standard is outdated, and we need to work to avoid a recurrence of the contamination at Hong Kong housing estates

This revelation set off a circular firing squad of accusations and investigations centring on how lead solder, which has long been banned, found its way into the estate’s water pipes. Terms such as “scare”, “scandal”, “dangerous”, “crisis” and “toxic” filled the media and the speeches of politicians.

The government set up three task forces and the Water Services Department took thousands of samples at both “affected” estates and “unaffected” ones. On May 11, one of those task forces, the Commission of Inquiry into Excess Lead Found in Drinking Water, submitted its report to the chief executive. The government is now mulling over the results.

What tends to get ignored in all this hullabaloo is the magic number of 10ppb. Where did the WHO get this figure? What does it mean? Is 11ppb a scandalous figure? Is 9ppb safe? The answer in both cases would seem to be “no”.

Hong Kong is not Flint, Michigan, where some of America’s poorest people paid one of the highest rates in the country for water that, in some cases, exceeded the levels set for toxic waste (5,000ppb). It is also not the China on the other side of the border, where a 1984 WHO standard of 50ppb is still used.

It is not the US, where users are urged to take action if they discover 15ppb in their drinking water. If it is from their own pipes after untainted water is supplied from the mains, it is up to them to fix it, not the water agency. Over 40 million Americans are estimated to drink levels higher than this. Perhaps that explains the Donald Trump phenomenon.

Compared to a large part of the world, then, people in Hong Kong are actually more likely to drink tap water that is relatively free of lead. So is there cause for worry? Well, for many people, unfortunately yes, but probably not a lot.

The WHO relies on an expert committee, which goes by the acronym of Jecfa, to survey the current state of scientific knowledge regarding possible hazards to health. In 1986, the committee proposed a “provisional tolerable weekly intake” of 25ppb based on studies of infants that indicated they did not retain lead at levels lower than that. This works out to 10ppb for a 5kg bottle-fed infant drinking 0.75 litres of water per day, with the additional assumption that it receives half of its lead intake from somewhere else, such as old lead paint.

Since those other sources of lead have become less common in the past 30 years, and the standards were set for the most vulnerable in the population, 10ppb would seem to be an overly cautious standard. Even doubling that should not be a matter of great concern, possibly even for the most vulnerable populations.

Unfortunately, as the amount of lead we are exposed to has declined, the results from more recent scientific studies are far from reassuring. Lead in any amount appears to affect health to some extent.

Newer epidemiological studies reviewed by Jecfa in 2011 found that there are no safe levels. The old tolerable intake is not really tolerable. It is associated with a decrease of at least three IQ points in children and an increase in systolic blood pressure of three points in adults.

The WHO has kept the standard at 10ppb on practical grounds, not for reasons of health. There is little magic in this number. The only good lead in tap water is no lead. When it is detected at any level – but particularly over 5ppb – the cause should be determined and, to the extent possible, fixed.

In Hong Kong, the contamination came from the use of cheap but prohibited lead solder in the pipes

In Hong Kong, it has already been determined that the contamination came from the use of cheap but prohibited lead solder in the pipes of the estates. This all needs to be replaced, preferably by those who put it there, and oversight systems put in place to prevent a recurrence.

Life is filled with risks, some of which, like eating fast food or walking across a busy street, are our choice. Others, like the air we breathe or the water from the tap of a housing estate, are not. Some risks we know about and others we don’t.

Lead is a known health risk; what was not known was that it is in Hong Kong’s tap water when it should not have been. Now we know. It should not happen again. Think how smart and heart-healthy those of us who were raised in the days of leaded gasoline could have been!

Professor James E. Nickum is an adviser at the Water Governance Research Programme, University of Hong Kong