Don’t blame globalisation for all society’s ills, in Hong Kong or elsewhere

Farzana Aslam says the much-maligned economic model has been steered recklessly and the rise of localist forces around the globe makes it incumbent upon policymakers to find ways to balance global concerns with local issues

Hong Kong “localists” are outspoken over the question of autonomy, but the political platform upon which they have garnered support is a protest against the establishment and its failure to address the pressing social issues that affect Hong Kong as a community – namely, rising inequality, the lack of affordable housing and the public’s perception that government is serving the interests of big business at the expense of the increasing ranks of the poor. It is a common thread that runs through all political shifts occurring around the globe.

Outside of Hong Kong, the rhetoric has been squarely directed against globalisation, specifically international trade and open borders allowing the free flow of capital and people. This, however, is to equate the forces of globalisation with the forces that drive inequality, the stagnation of real incomes, the erosion of job security and of welfare services provided by the state.

Politicians worldwide have been too ready to invoke globalisation as the cause of their domestic woes, when the reality is that the decline in the prosperity and social well-being of the average citizen of these nations has been the result of deliberate domestic policies promoted under the banner of globalisation.

Globalisation can be a force for good if accompanied by good governance and responsible policymaking to ensure a fairer distribution of its rewards

As a consequence, investment in areas of public and civic life that have traditionally fallen within the purview and care of the state, such as health care, education and vocational training, housing and job creation have been largely outsourced to the exigencies of the free market.

Alongside laissez-faire economic policies, the era of globalisation has been marked by an abject failure to institute adequate mechanisms for regulation of the free market. This has resulted in a governance gap that, aside from being largely responsible for the economic crisis of 2008, has allowed multinationals to expand their wealth base, yet minimise – and in many cases avoid – their exposure to the payment of domestic taxes.

Rather than accept accountability for these failings in leadership that have operated at a local and inter-national level, politicians offer up “globalisation” as an explanation. Reference to “global” invites the public to believe that the negative consequences of local economic policies that have accompanied globalisation are driven by an invisible hand, a power beyond the control of local policymakers. This is nonsensical. For example, when politicians deride free trade, they conveniently forget that international trade agreements are always negotiated between nation states.

In the case of the US, their trade agreements have historically been heavily one-sided negotiations that have encouraged (at the force of a penalty) developing countries to maintain low wage levels and at the same time discourage the development of local labour rights, such as the ability to unionise.

While this policy has enabled the production of cheap imports to fuel consumption patterns of American households, it has also served to suppress wage increases among the working population of their trading partners to levels that would more readily compete with US wages. The American manufacturing industry has been decimated as a result, with many workers left disenfranchised and dislocated. It is only in recent trade negotiations such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership that the US has reversed this policy by insisting that its trading partners institute the protection of labour rights including a minimum wage in order to encourage a “level playing field” with workers back home.

International trade and open borders are not inherently bad for the economic prosperity of any given nation state. Indeed they are necessary

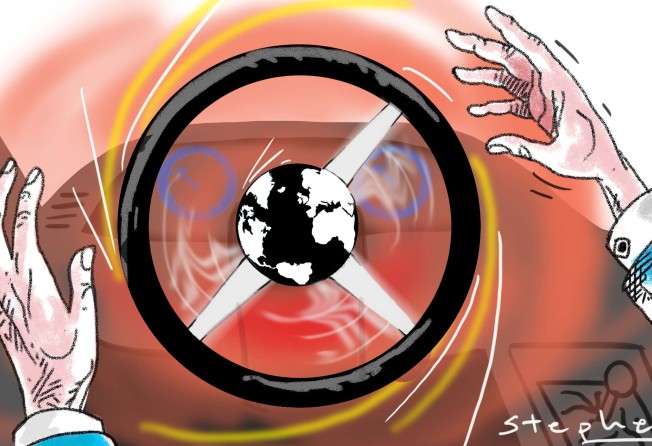

My point is that globalisation is not a wild uncontrollable force; it has simply been steered in a manner that has, to date, been short-sighted and reckless.

International trade and open borders are not inherently bad for the economic prosperity of any given nation state. Indeed they are necessary for the very countries that are now decrying them as evil. Many wealthy nations are facing a demographic crisis – their declining working age populations desperately need immigrant labour to allow their economies to grow. Equally, without international trading partners, most national economies would not survive. Isolationism and protectionism is not the answer.

Globalisation can be a force for good if accompanied by good governance and responsible policymaking to ensure a fairer distribution of its rewards. What is desperately needed is a socially responsible approach that will navigate globalisation with due accord to issues of local concern: a “glocalisation” of politics.

Let’s hope Hong Kong’s sixth Legco is up to the task and can focus on both Hong Kong’s local and global affairs in a way that continues to safeguard the city’s success as a global centre while at the same time addressing the concerns of local people whose interests lawmakers have been elected to represent.

Farzana Aslam is associate director of the Centre for Comparative and Public Law and principal lecturer in the Faculty of Law at the University of Hong Kong