Chinese history can open the eyes of Hong Kong students, just don’t try to doctor it

Kerry Kennedy says if done right, the teaching of national history can help students grow into discerning individuals able to make their own judgments about their nation and national identity

In reality, it is not such a new refrain. The melody has been playing since July 1, 1997, accompanied by both calls and action to build a strong national identity for China’s new citizens. The current refrain has led to cries of “brainwashing” from the opposing camp that only ever seem to be in reaction mode to any initiative associated with pro-China groups.

Both sides obscure what should be a serious debate about what young people in Hong Kong should know and be able to do as a result of their school learning experiences.

The problem, when it comes to teaching Chinese history, is what history and whose history will be taught

It is not unusual, for example, for national history to be part of the learning experiences of young people as they prepare to be citizens. It is the case in the United States, Australia and the UK.

The teaching of national history is not inimical to democracy. If done well, it can be a strong support for democratic development and engagement. Yet there are always debates about the teaching of national history.

The current Conservative government in Britain wanted to see British history given more emphasis, even in primary school, causing a considerable community backlash. In Australia, when John Howard became prime minister, he wanted to do away with what he called “the black armband” view of history. He preferred instead to celebrate the progress of British civilisation rather than remember the carnage it wrought on indigenous people and the environment.

In the US, there are supporters of “black history”, “women’s history” and “Latina/Latino history” as part of the national story. Thus, the teaching of history is always contested.

Watch: Retracing the events of the 1967 riots in Hong Kong

History is not an objective science governed by laws as is the case in physics and chemistry. “History is written by the victors”, is a quote often attributed to Winston Churchill. Imagine how the history of Taiwan appears in textbooks in mainland China and how it is written in Taiwan. How would it be written in Hong Kong textbooks?

The same question can be phrased for the events of 1989 in Tiananmen Square. The events are largely missing from mainland history texts, but what would be the case in Hong Kong?

The problem, when it comes to teaching Chinese history, is what history and whose history will be taught. Even more importantly, who will make these decisions about which version of history will make it into school textbooks?

Japan seems to solve this problem by having multiple textbooks from which school districts can choose. Different books are likely to support different “versions” of Japanese history – so the root problem of an endorsed national story remains unresolved.

Currently in Hong Kong, efforts are being made by the Education Bureau to revise the Chinese history syllabus but, as last year’s consultations showed, it is not easy to gain a consensus from either the teaching profession or the community. Forcing one version of history into the curriculum may indeed satisfy some people, but it will cause problems for others.

To decide, for example, that the 1967 riots should not be taught as part of Hong Kong’s history, that the Kuomintang’s role in defeating the Japanese should not be highlighted or the “cultural revolution” should not receive attention, is to make political decisions about what history is important.

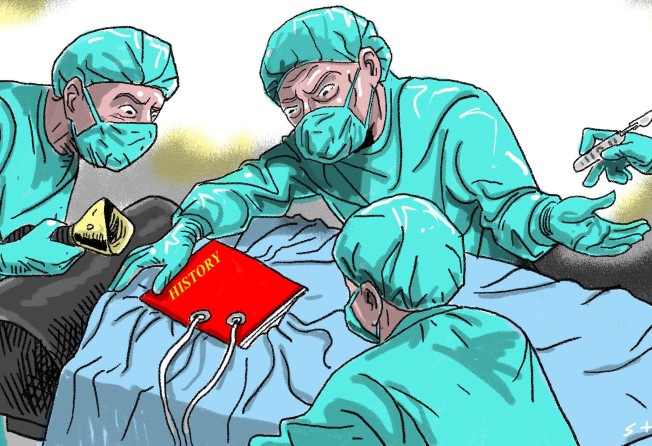

This is where the “brainwashing” accusations originate: when there are attempts to “doctor” history so that it suits one ideological view rather than another.

Such “doctoring” is a tactic of authoritarian regimes, insecure about their hold on power and anxious to develop a national story that suits their own aspirations rather than those of the people they should be serving. Such an approach should have no role in Hong Kong.

Giving young people a glimpse of their cultural foundations, insights into China’s political development and a grasp of the social issues that have confronted the nation should not be beyond the capacity of curriculum developers.

Chinese history can be a great learning experience when it is not used as a tool to promote a narrow ideology

But leave the ideology aside. Integrate the content with critical thinking and problem-solving skills, so that young people learn not only about specific aspects of the past but also develop the skills to investigate for themselves and make judgments about the nation of which they are a part.

Chinese history can be a great learning experience when it is not used as a tool to promote a narrow ideology and a distorted view of the world.

Professor Kerry Kennedy is a senior research fellow in the Centre for Governance and Citizenship at The Education University of Hong Kong