Doklam dispute shows India must pick its battles, as China seeks to be the centre of the world

Shyam Saran says while China’s rise is remarkable, a recast history is put forward to legitimise its claim to Asian hegemony, and its Doklam stance aims to weaken the regional alliance between India and Bhutan

India is embroiled in a prolonged stand-off with Chinese forces on the Doklam plateau. China may have been caught off guard after Indian armed forces confronted a Chinese road-building team in Bhutanese territory. Peaceful resolution of the issue requires awareness of the context for the unfolding events. China has engaged in incremental nibbling advances in this area, with Bhutanese protests followed by solemn commitments not to disturb the status quo. But the intrusions continued. This time, the Chinese signalled intention to establish a permanent presence, expecting the Bhutanese to acquiesce while underestimating India’s response.

Managing the China challenge requires understanding the history of the Chinese civilization and the world view of its people, formed over 5,000 years of tumultuous history.

The ideas of US naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan and British geographer Halford Mackinder are just as discernible in Chinese strategic thinking today as concepts derived from the ancient strategist, Sun Tzu. The “Belt and Road Initiative” is Mackinder and Mahan in equal measure: the belt, designed to secure Eurasia, dominance over which would grant global hegemony, was suggested by Mackinder in 1904; the road, which straddles the oceans, enabling maritime ascendancy, is indispensable in pursuing hegemony, according to Mahan in the late 19th century.

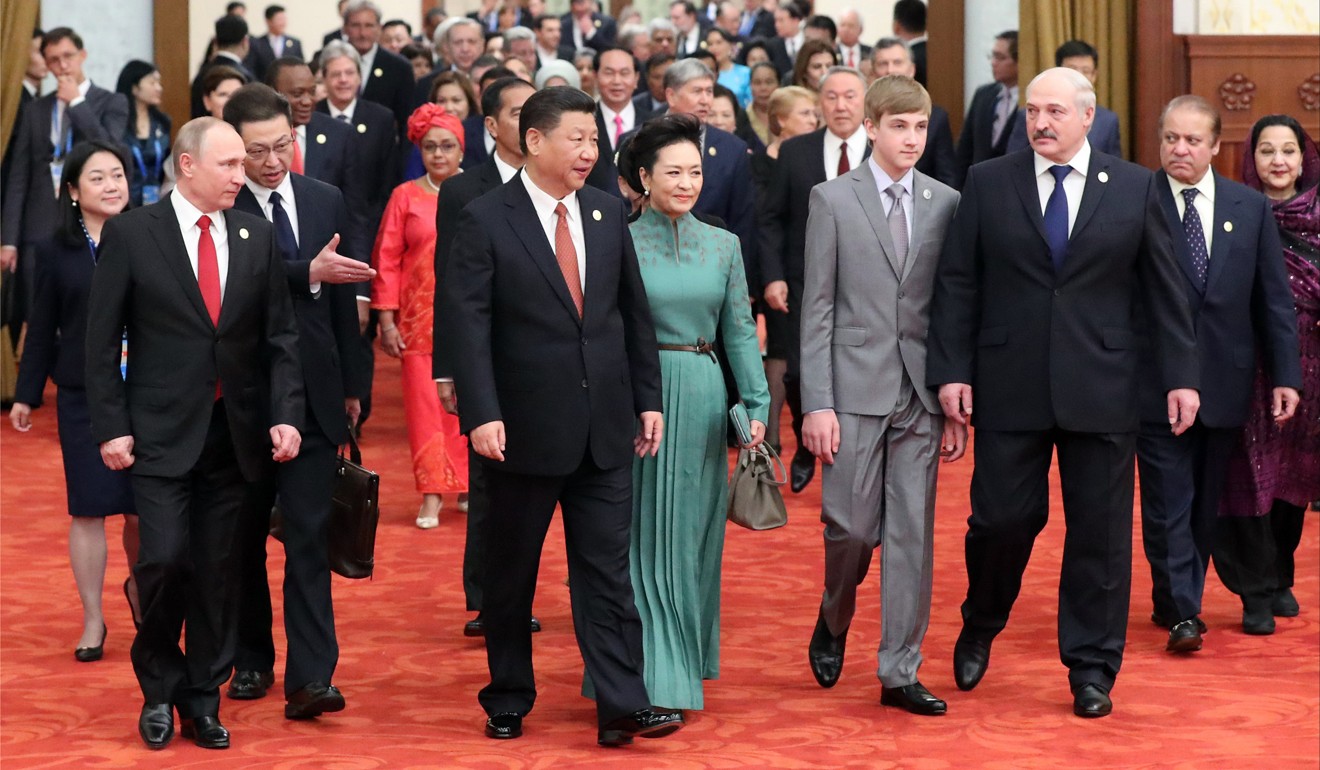

China’s pursuit of predominance at the top of the regional and global order, with the guarantee of order, has an unmistakable American flavour. It also echoes Confucius, who argued that harmony and hierarchy are intertwined.

China uses templates of the past ... to construct a modern narrative of power

China uses templates of the past as instruments of legitimisation, to construct a modern narrative of power. One key element of the narrative is that China’s role as Asia’s dominant power restores a position the nation occupied through most of history. The period from the mid-18th century until China’s liberation in 1949, when the country was reduced to semi-colonial status, subjected to invasions by imperialist powers and Japan, is characterised as an aberration. The tributary system is presented as artful statecraft evolved by China to manage interstate relationships in an asymmetrical world. What is rarely acknowledged is that China was a frequent tributary to keep marauding tribes at bay. The Tang emperor paid tribute to the Tibetans as well as to the fierce Xiongnu tribes to keep the peace.

History shows a few periods when its periphery was occupied by relatively weaker states. China itself was occupied and ruled by non-Han invaders, including the Mongols, from the 12th to 15th centuries, and the Manchus, from the 15th to 20th centuries. Far from considering these empires as oppressive, modern Chinese political discourse seeks to project itself as a successor state entitled to territorial acquisitions of those empires, including vast non-Han areas such as Xinjiang ( 新疆 ) and Tibet.

Thus, an imagined history is put forward to legitimise China’s claim to Asian hegemony, and remarkably, much of this is increasingly considered as self-evident in Western and even Indian discourse.

Little in history supports the proposition that China was the centre of the Asian universe commanding deference among less civilised states. China’s contemporary rise is remarkable, but does not entitle it to claim a fictitious centrality bestowed upon it by history.

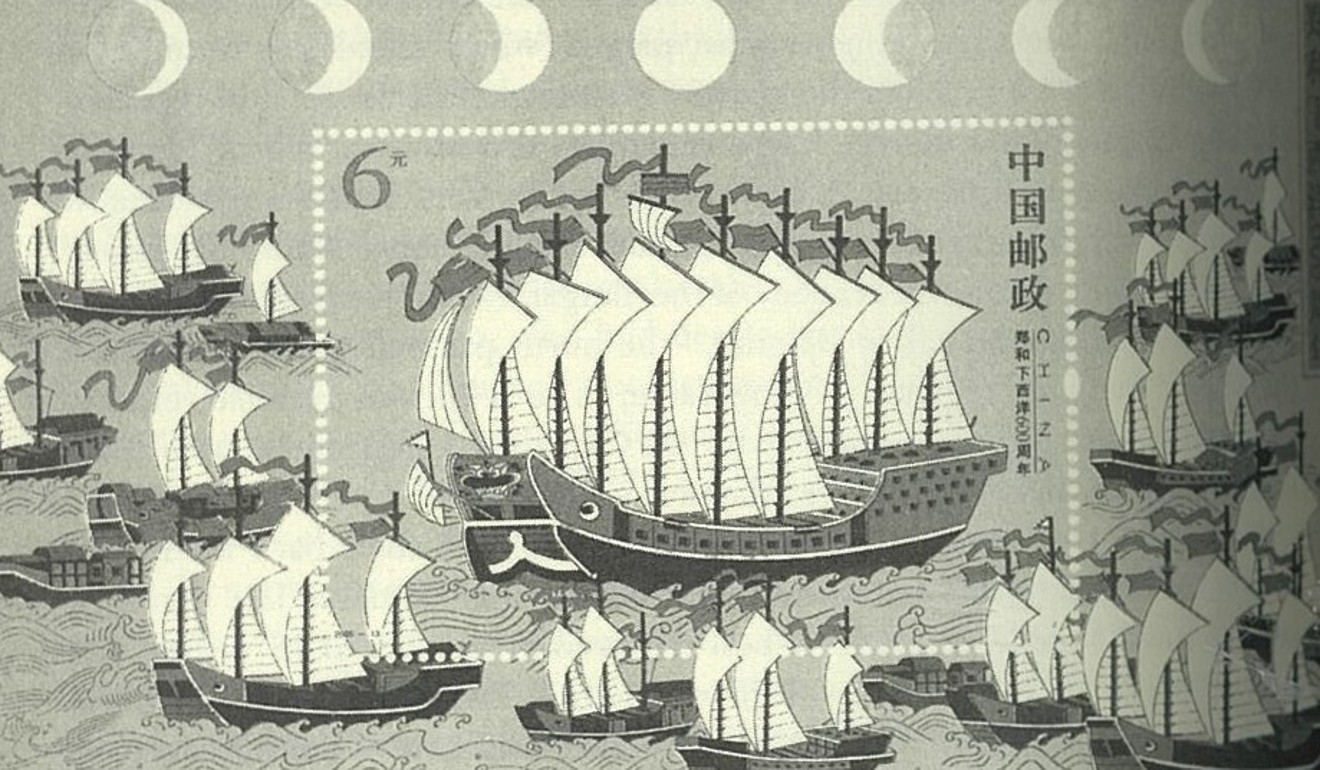

The belt and road also seeks to promote the notion that China through most of its history was the hub for trade and transport routes radiating across Central Asia to Europe, and across the seas to Southeast Asia, maritime Europe and even the eastern coast of Africa. China was among many nations that participated in a network of caravan and shipping routes crisscrossing the ancient landscape before the advent of European imperialism. Other great trading nations included the ancient Greeks and Persians, and later the Arabs. Much of the Silk Road trade was in the hands of the Sogdians who inhabited the oasis towns leading from India in the east and Persia in the west into western China.

Thus, recasting a complex history to reflect a Chinese centrality that never existed is part of China’s current narrative of power.

Yet large sections of Asian and Western opinion already concede to China the role of a predominant power, assuming that it may be best to acquiesce to inevitability. The Chinese are delighted to be benchmarked to the US with the corollary, as argued by Harvard University’s Graham Allison, that the latter must accommodate China to avoid inevitable conflict between established and rising power.

However, in other metrics of power, with the exception of GDP, China lags behind the United States, which still leads in military capabilities and scientific and technological advancements.

In reality, neither Asia nor the world is China-centric. China may continue to expand its capabilities and may even become the most powerful country in the world. But the emerging world is likely to be home to a cluster of major powers, old and new.

The Chinese economy is slowing, similar to other major economies. It has an ageing population, an ecologically ravaged landscape and mounting debt that is 250 per cent of GDP. China also remains a brittle and opaque polity. Its historical insularity is at odds with the cosmopolitanism that an interconnected world demands of any aspiring global power.

Any emerging and potentially threatening power will confront resistance. China, like other nations before it, cultivates an aura of overwhelming power and invincibility to prevent resistance.

Despite this, coalitions are forming in the region, with significant increases in military expenditures and security capabilities by Asia-Pacific countries.

Doklam should be seen from this perspective. The enhanced Chinese activity is directed towards weakening India’s close and privileged relationship with Bhutan, opening the door to China’s entry and settlement of the Sino-Bhutan border, advancing Chinese security interests vis-à-vis India.

India has to carefully select a few key issues where it has to confront China, avoiding annoyances not vital to national security. Doklam is a significant security challenge.

Shyam Saran has served as India’s foreign secretary and as chairman of its National Security Advisory Board. This article is adapted from the inaugural lecture delivered by the author at the Institute of Chinese Studies and the India International Centre, New Delhi. Reprinted with permission from YaleGlobal Online. http://yaleglobal.yale.edu