Money alone can’t build China a thriving movie industry

Audrey Li says as long as China continues to deny its filmmakers the freedom to create, the country will never have the kind of cultural influence it seeks, whatever the ambitions of tycoons like Wang Jianlin

Chinese tycoon Wang Jianlin, chairman of Dalian Wanda, has sold off 70 billion yuan’s (HK$81 billion) worth of assets since the real estate and entertainment conglomerate’s loan records came under strict scrutiny from China’s banking regulator. Among the properties sold, a yet-to-be-completed massive film studio complex in the port city of Qingdao (青島) was let go cheaply.

Just four years ago, Wang had announced his plans for a “Hollywood of the East” at a red-carpet event attended by Hollywood superstars, including Leonardo DiCaprio, Nicole Kidman and Catherine Zeta-Jones. Media around the world took notice: China’s richest man is going to build “Chollywood”, or China’s Hollywood.

Wang has never been shy about his ambition. In a few short years, he has acquired a global entertainment business with the US$2.6 billion purchase in 2012 of AMC, the US-based cinema chain, and the US$3.5 billion acquisition last year of the US film studio Legendary Entertainment.

Things did not always go his way, however. After announcing his ambition to buy stakes in the top six Hollywood studios, his attempt to invest in Paramount was spurned by the studio. Then in March, his planned US$1 billion purchase of Dick Clark Productions, the production company behind the Golden Globe Awards, also fell through amid China’s concerns over outbound investment draining the country’s foreign currency reserves.

Regardless of Wanda’s setbacks, the “money talks” strategy works, in a way. Hollywood is increasingly reliant on Chinese money, whether in terms of financing or box office receipts. From Warcraft to The Fast and the Furious 8 , from Resident Evil: The Final Chapter to xXx: Return of Xander Cage , China’s box office has time and again outperformed North America’s.

As well, Chinese-Hollywood co-productions are exempt from the quota of 34 Hollywood films that are allowed on Chinese screens each year on a revenue-sharing basis (though the quota is now under review). As a result, more and more Chinese performers are showing up on Hollywood screens, even if for just a few seconds saying only a line or two, like Jing Tian in Kong: Skull Island and Fan Bingbing in X-Men: Days of Future Past .

Meanwhile, Hollywood is learning to deal with China’s “movie watchdogs”. Producers self-censor from the very beginning of production to avoid any casting, script or poster decisions that could potentially offend “the feelings of the Chinese people”.

As Aynne Kokas observed in her book, Hollywood Made in China, under pressure from the market and investors, producers were obviously adjusting their stories according to “unwritten rules”.

Given China’s financial heft and its huge market, can China emerge a player of global importance? Perhaps. Unfortunately, it won’t be any time soon.

Money does not guarantee quality, as we know. In February, The Great Wall , the high-profile co-production film starring Matt Damon as an English mercenary during China’s Song dynasty, did poorly at the US box office although most of the lines were in English. As one critic put it: “If ever a film was made with more money than sense, this is it.”

This outcome may cloud prospects for Qingdao’s “Oriental Movie Metropolis”, the Chinese studio where part of the movie was filmed, and which Wanda once had great expectations of but eventually sold.

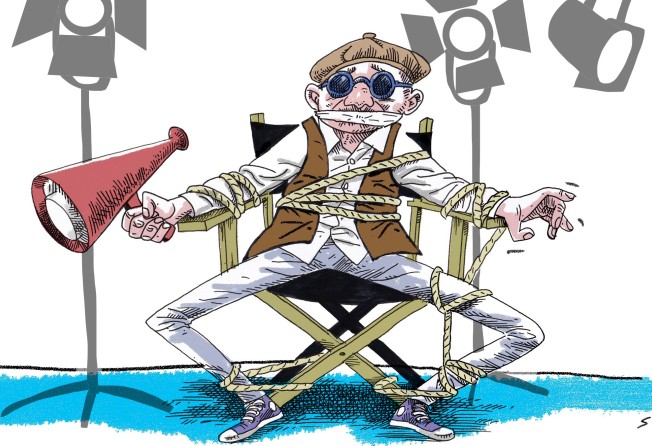

One major obstacle stands in China’s way of being culturally influential. Its increasingly draconian censorship puts shackles on its filmmakers. Once a movie fails to gain approval of the censors, the investment and the efforts of the entire crew go down the drain. No one knows for sure where the line lies between what is allowed and what isn’t.

To the censors, an ambiguous and somewhat arbitrary line is always far more powerful than a clear one. “Those directives are so outrageous and absurd that you don’t know whether to laugh or cry,” director Feng Xiaogang said in 2013. “For the last 20 years, every director in China has faced a kind of tremendous torment, and that torment is censorship.”

The absence of the freedom of expression leads to the lack of high-quality works, and in the long run that leads to the degradation of movies goers’ taste. It hurts the industry when shoddily produced films make fat profits and really good works get no attention.

It is reported that directors are now willing to add characters or amend scripts merely for the sake of the so-called “little fresh meat” (xiao xian rou), that is, good-looking young male actors who have a huge following but little professional experience in performing.

Despite these difficulties, there have been quite a few outstanding independent filmmakers doing their best to earn international recognition. However, the authorities have never appreciated the unauthorised export of the films they produce. From Lou Ye to Wang Xiaoshuai, directors saw their works banned from Chinese screens after receiving warm receptions in Cannes or Berlin. Director Tian Zhuangzhuang was even forced to stay out of the profession for eight years because of his globally acclaimed Cultural Revolution-themed movie, The Blue Kite.

There is no sign of a loosening of the heavy-handed ideological control in the film industry. This June, citing “official pressures”, the French Annecy International Animated Film Festival, the world’s biggest animation festival, was forced to remove Liu Jian’s Have a Nice Day, a dark comedy about gangster capers, which was seen by the authorities as painting a bleak and dreary picture of contemporary China.

In this regard, the obstacles to fulfil the “Chollywood” dream seem far more challenging than the difficulties Wang Jianlin faces when hunting for another overseas acquisition.

Audrey Jiajia Li a freelance columnist and China observer based in Guangzhou