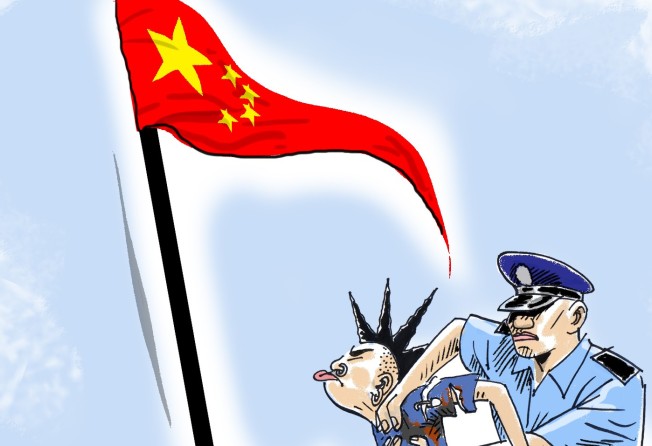

Does respect for China’s national anthem have to be mandated by law in Hong Kong?

Cliff Buddle says criminalising derogatory treatment of the national anthem, while intended to protect it, would nevertheless curb freedom of expression. Worse, the proposal comes at a sensitive time in Beijing-Hong Kong relations

When the Sex Pistols released their punk version of Britain’s national anthem in 1977, the country’s establishment reacted with horror and outrage.

The BBC banned the song from the airwaves, some stores refused to sell the single, and the band came under fire from the media and the public. There were even scuffles and arrests during a provocative publicity stunt when the song was played on a boat on the River Thames.

Forty years on, the punk anthem might strike a chord with Hong Kong’s disaffected youth, with its uncompromising anti-establishment message and refrain of “no future for you … no future for me”.

But any attempt to subject China’s national anthem, March of the Volunteers, to similar treatment could, in future, land those responsible in jail. A law on China's national anthem was passed by China's top legislature on Friday. It is a national law, which means it does not automatically apply to Hong Kong. But the intention is to bring it into force in the city by following procedures set out in Hong Kong’s de facto constitution, the Basic Law.

Zhang Haiyang, deputy head of the NPC law committee, said the legislation is necessary to foster socialist core values and to promote the patriotism-centred spirit of the nation.

The law bans malicious altering of the lyrics in a derogatory manner in public.

Latter-day Sex Pistols beware!

It also limits the occasions when the national anthem may be played. Using it in advertisements, as background music in public places, or at funerals, is not allowed. The law requires everyone to respect the national anthem. When it is played, those present are to stand in a respectful manner. A breach of the law can result in 15 days police detention. Violations can also be dealt with under other laws.

National anthems, as a reflection of a country’s identity, history and culture, are entitled to respect. It is not surprising this one is being applied to Hong Kong given that, as part of China, it is the city’s national anthem, too.

Watch: how well do Hongkongers know their national anthem?

However, a law which makes disrespecting the national anthem a crime will curb free expression. Concerns have already been expressed about the impact it will have. And it comes at a time of heightened sensitivity about moves by Beijing to use the law to further its objectives in Hong Kong.

The city’s leader ,Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, has said the law will be applied through local legislation. That is necessary, because some parts of it simply will not work under the city’s separate legal system. There is no detention without trial in Hong Kong. The draft law’s requirements for the media to promote the national anthem and for it to be included in school music curriculums would appear to conflict with provisions of the Basic Law protecting press freedom and preserving the city’s autonomy over education.

It is very important that the law is clear and precise so that everyone understands what constitutes an offence. If it is too broad, the courts are likely to view it as an unlawful restriction on the freedom of expression and strike it out.

Pro-establishment lawmakers have suggested that booing the national anthem at a football match will breach the law. Whether or not that is the case will need to be made clear.

Watch: Hong Kong soccer fans boo the national anthem in 2015

Hong Kong fans started booing the national anthem at football matches in 2014, following the Occupy pro-democracy protests that year. It is difficult to see how a law against this would be enforced. What are the police to do? Arrest the crowd at Mong Kok Stadium? Do we really want to impose criminal sanctions on young people holding up a sign saying “boo” when the national anthem is played? What if someone fails to stand up or forgets the words? Is that also a matter for the police?

What if someone fails to stand up or forgets the words? Is that also a matter for the police?

Whatever form the law passed by the Legislative Council takes, it is likely to be breached. This will mean another controversial court case in which the constitutionality of the law is tested. That is what happened in 1999 after a national law criminalising desecration of China’s flag was applied to Hong Kong. The Court of Final Appeal upheld the flag law, which carries a maximum sentence of three years’ imprisonment. But its judgment was criticised because the majority of the judges relied on the vague legal concept “ordre public”, which was seen as a weak basis for justifying a restriction on human rights.

The March of the Volunteers has a colourful history. Written in the 1930s, it became a rallying cry for the people of China during the war with Japan. It was later adopted as the national anthem of the People’s Republic of China, although the lyrics were at one point changed to incorporate references to Mao Zedong. The original words were restored in 1982.

Watch: The sad history of China’s national anthem

Student protesters sang the anthem in Tiananmen Square in 1989 before the crackdown.

Laws protecting national anthems exist elsewhere in the world and are occasionally a source of controversy. India’s Supreme Court ruled last year that people should stand up in respect for the country’s national anthem when it is played in cinemas and there have been cases of people being arrested for failing to do so.

In Japan, teachers have been disciplined for refusing to stand during the playing of the national anthem at schools, because they associated the song with country’s military past.

In the US, the law encourages people to respect the national anthem but there are no criminal penalties for failing to do so.

Times have changed in Britain in the 40 years since the release of the Sex Pistols single. A Conservative Member of Parliament recently called for the national anthem to be played by the BBC at the end of its day’s television programming, as happened until 1997. BBC’s Newsnight programme responded by saying it was happy to oblige – it played the Sex Pistols version.

It is natural for governments to expect their country’s national anthem to be respected. But the addition of another law which criminalises a form of expression is not what Hong Kong needs at this politically sensitive time. To borrow from the Sex Pistols song, it’s a “potential H-bomb”.

Cliff Buddle is the Post’s editor of special projects