Lesson from Doklam: China and India can still become ‘Chindia’, but only when boundaries are set

Xu Xiaobing says the Sino-Indian relationship of rivalry has also seen cooperative coexistence, especially on the cultural level. But Doklam shows all cordiality hinges on compliance with international law

Chindia, a portmanteau word coined by India, refers to China and India together. In reality, however, making the two giant neighbours more intimate is easier said than done.

For our generation, the Sino-India relationship, hindered by their craggy and combative frontier, has been an overall competitive, somewhat complementary and cooperative, but usually confrontational, and occasionally cinematic, coexistence.

To begin with, there is a long history of communication between the two countries. The spread of Buddhism from India to China and trade with Europe through the Silk Road are examples of early contact. Today, there is increased bilateral and multilateral cooperation, both inside and outside the BRICS bloc.

It is also true that the two share significant similarities and differences. For instance, they are known as the world’s biggest developing countries, that together account for more than one-third of the world’s population, and are among the fastest growing major economies. But, politically, China is tagged as the largest single-party state while India is the largest democracy.

The two nations seem inherently competitive, and the rivalry seems to range from GDP figures to “big power” status, from space programmes to military advancement, and from natural resources to even world cultural heritage application for Tibetan medicine, to name just a few. To rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative, India launched “Project Mausam”, in a bid to counterbalance China’s increasing influence in the region and the world.

But despite the competition between the Chinese “dragon” and the Indian “elephant”, the two economies are considered somewhat complementary and have great potential for pragmatic and mutually beneficial cooperation. For example, China is seen as strong in manufacturing and infrastructure, while India is strong in services and information technology.

Delhi-Beijing ties experienced a honeymoon after diplomatic relations were established in 1950

There were surely good moments in the relationship. I call these good times “cinematic” because, more often than not, a popular Indian movie in China may best catch the mood of the time.

The Indian film industry, represented by the prolific Bollywood, has in those good times earned numerous fans in China. For example, Delhi-Beijing ties experienced a honeymoon after diplomatic relations were established in 1950. The Bollywood movie Awaara (nominated for the 1953 Golden Palm at Cannes) was introduced to China in 1955 and soon became a big hit. After diplomatic relations at the ambassadorial level were resumed in 1976, after a 15-year hiatus, the film was re-released in China in 1978, and the title song Awaara Hoon was sung all over the country. Recent examples include Three Idiots (released in China in December 2011), Baahubali (in June last year), and Dangal (in May). Dangal’s box office collections in China were reportedly twice that in India.

Chinese fans of Dangal recreate moves from the film

Unfortunately, ever since the border war in 1962, good times in the Sino-Indian relationship have become rare and prone to be interrupted by confrontations.

China and India share about 2,000km of craggy terrestrial borders. Except for a few places, such as the “Sikkim sector” which was settled by the 1890 Convention between Britain and China relating to Sikkim and Tibet, almost the whole borderline is in dispute.

The border dispute can trace its history back to the early years of the bilateral relationship, after India achieved independence in 1947. It started to smell of gunpowder from February 1951, when the Indian army invaded and occupied the district of Tawang and expelled all administrative staff dispatched by the local Tibetan government. In October 1954, after prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s visit to China, India incorporated the McMahon Line (a legacy of British colonialism) in its official map, which China considers illegal. In 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India after China suppressed the Tibet rebellion. A series of incidents eventually led to the month-long 1962 border war, from October 20 to November 21.

The war opened a Pandora’s box, despite the fact that the two states have maintained relative peace since then. The combative mood at the mountainous frontier has not only sustained but hijacked the bilateral relationship, for more than half a century. The 72-day Dong Lang (Doklam) stand-off from mid-June to August is the worst and most recent indication.

Foreign Ministry calls the Indian incursion into Dong Lang ‘very serious’

It is quite ironic that China and India are actually the original advocates of the so-called “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence”, namely, mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity; mutual non-aggression; mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful coexistence.

In essence, the five principles reflect the core of the general principles of international law. In other words, the peaceful coexistence of nations requires their compliance with international law. And such compliance is vital for any normal and healthy bilateral relationship.

However, since its independence from colonial rule, India has adopted a policy of hegemony towards its smaller neighbours, in blatant disregard of international law. India not only flagrantly annexed Sikkim, a sovereign state, in 1975, but has also bullied Bhutan and Nepal over the years.

In its relationship with Nepal, India has frequently used economic sanctions to compel obedience from this landlocked country. The most recent example is the blockade of the India-Nepal border in 2015 after Nepal adopted its new constitution.

In the Sino-Indian relationship, international law plays a crucial role, too. The stand-off at Doklam was triggered by India, in a clear violation of international law.

China and India are both great nations. Each is an ancient civilisation that suffered a long period of colonial or semi-colonial rule and is now en route to national revival.

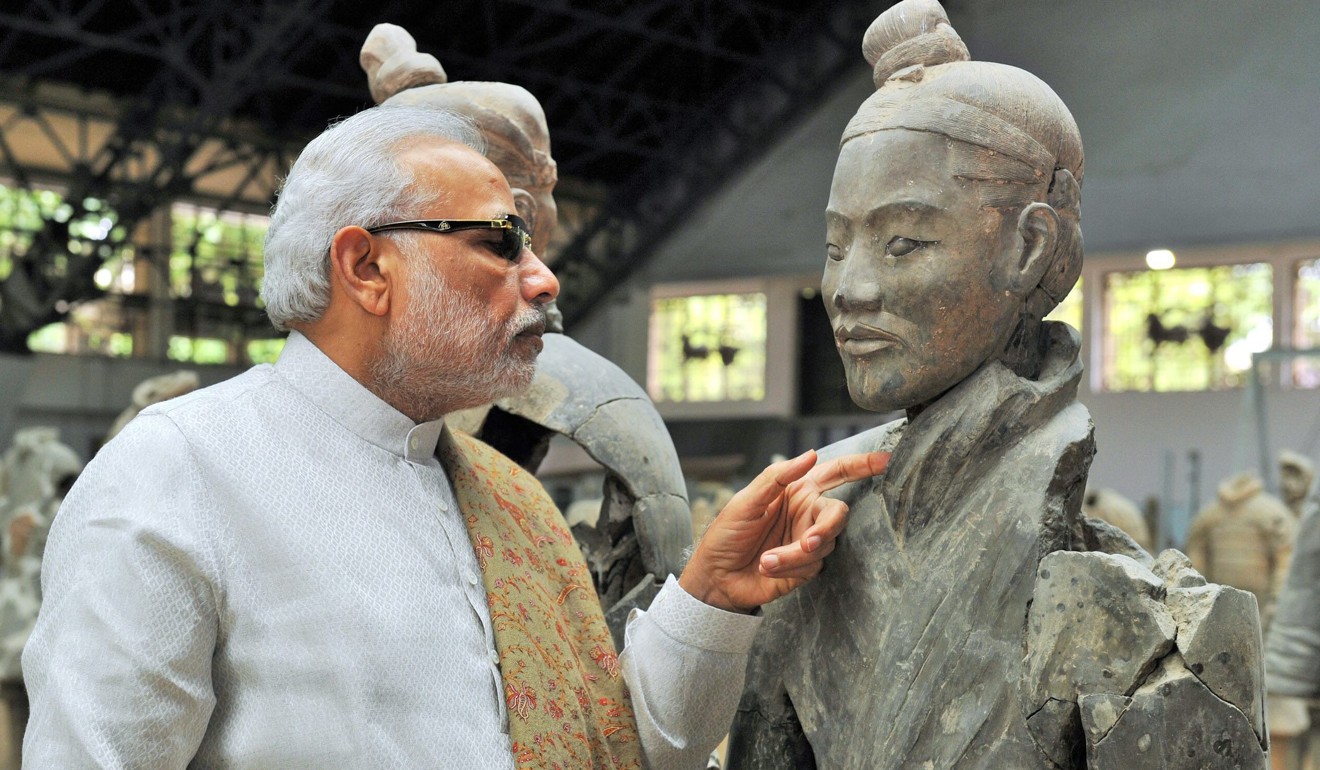

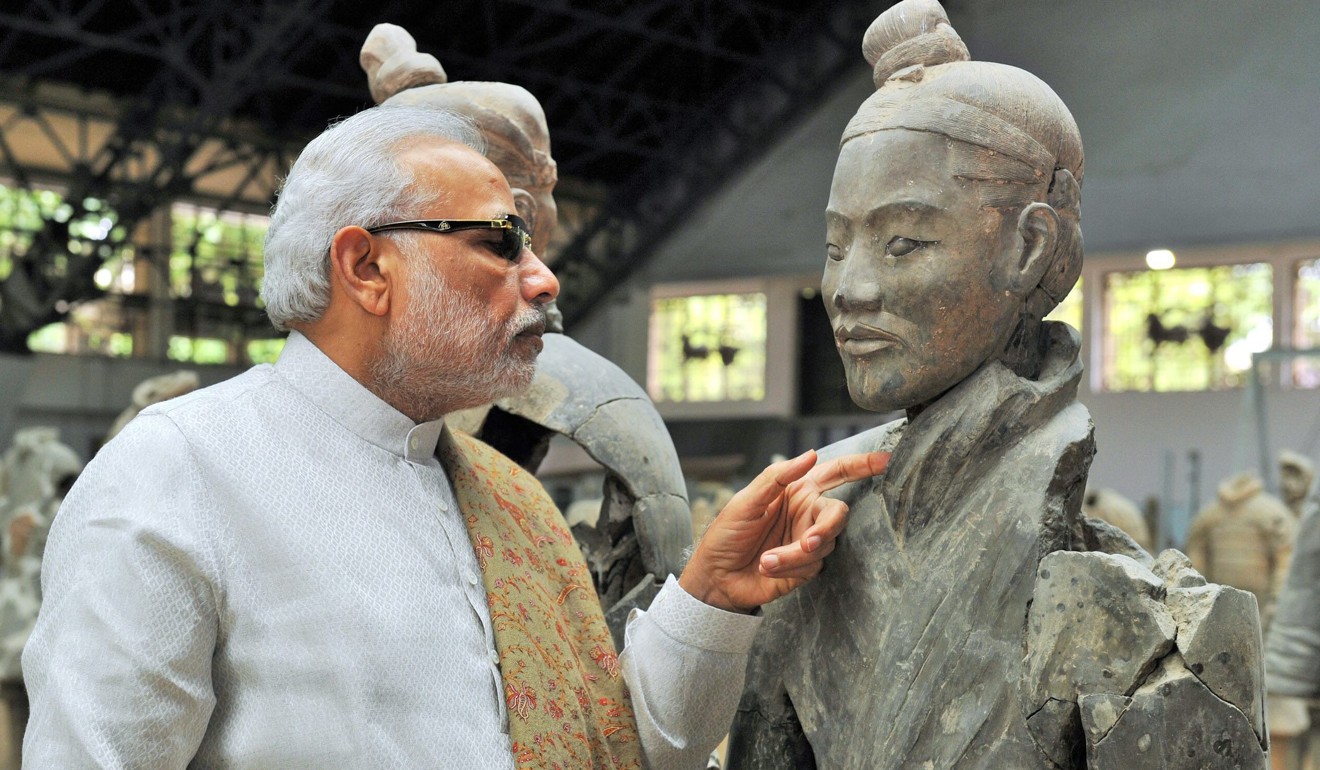

If the China and India of 2017 are different from the China and India of 1962, the difference lies in the fact that this time the two nuclear powers wisely avoided letting an accidental stand-off escalate into a major armed conflict. Instead, they chose to work together at the BRICS summit in Xiamen, where President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Narendra Modi met and agreed to develop stable relations.

Craggy and combative as their frontier may still be, there must be paths for Chindia to coexist, and connect in peace and respect. Compliance with international law is an obvious one.

Dr Xu Xiaobing is associate professor of law at Shanghai Jiao Tong University KoGuan Law School