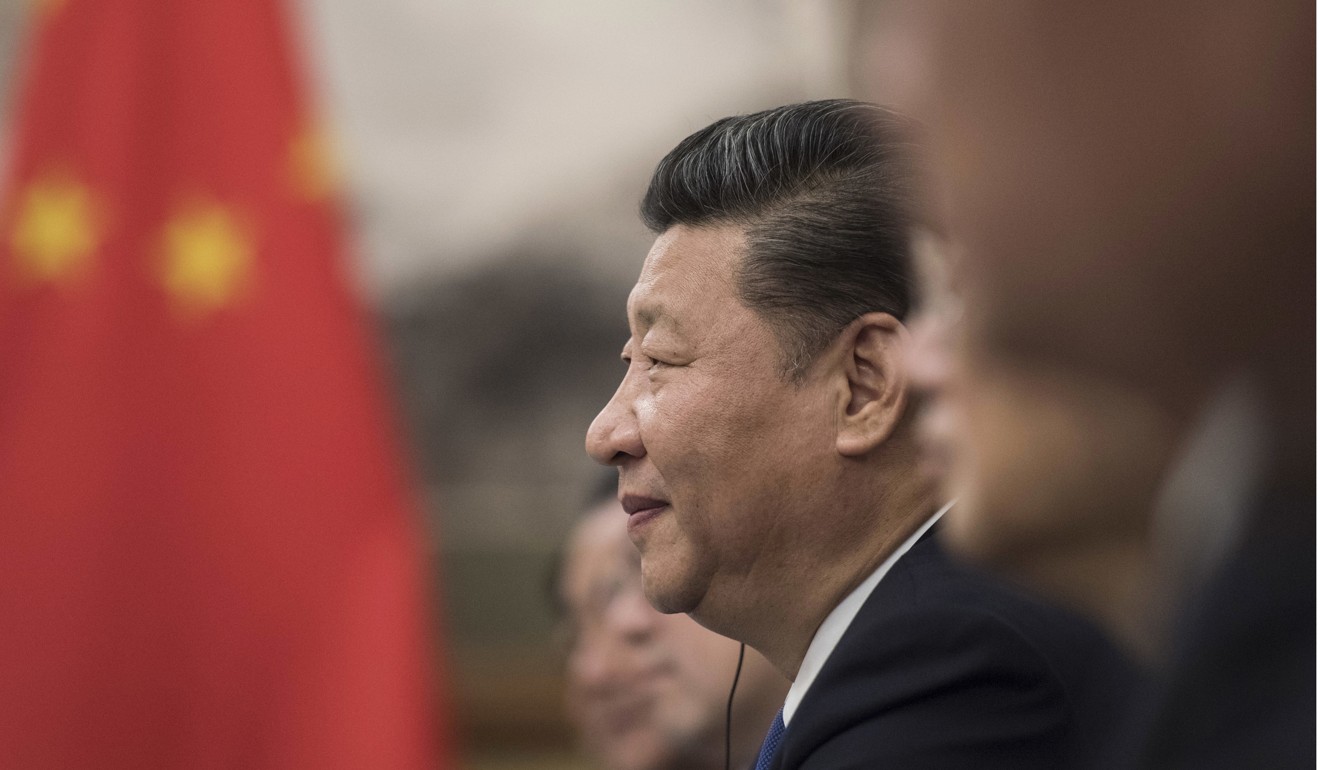

China, under Xi Jinping, embarks on a quest to win the trust of its people

Robert Lawrence Kuhn says the public uproar over two recent, unrelated incidents – alleged child abuse at a kindergarten and the eviction of migrant workers in Beijing – highlights how the Chinese leader was right in diagnosing society’s fundamental problem today

The first was alleged child abuse at a kindergarten. When authorities claimed that the hard disk of the surveillance camera had broken and that the recovered data showed no evidence of abuse, netizens ridiculed the claim and suspected a cover-up. What’s worse, they said, is that the police accused two parents of spreading rumours of the abuse. Angered netizens criticised authorities for enabling the alleged abuser to mask the truth. And when the online criticism was censored, anger escalated.

The second event was a fire in which 19 people died. All were migrant workers and, within days, many migrant workers were forced to leave their “illegal” apartments, literally, in some cases, thrown out into the cold, stoking more public anger. Again, social media, including WeChat, was cleansed of critical comments. The sense was that the local government was taking advantage of the fire by doing what it wanted to do anyway: reduce the number of migrant workers living in Beijing to create a beautiful Beijing of the future.

Even the Chinese state media criticised the local government, saying more “warmth” was needed in moving migrant workers. Sensitivities are so high that the Chinese media can no longer use the pejorative phrase “low-end population”.

Some Chinese scholars warn that the government is at risk of falling into the so-called “Tacitus trap”. The Roman historian Tacitus had observed that once a ruler became an object of hatred, the good and bad things he did only aroused people’s dislike of him. The Chinese scholars draw the analogy: “When a government department or an organisation loses its credibility, whether it tells truth or lies, does good or bad, the public believes them to be lies and bad.”

It may surprise Westerners that these two isolated incidents can trigger such heated emotions, even vitriol, towards the government. After all, such tragic or scandalous events are not uncommon in all countries. Why then have these caused such a stir in China, whereas in the US, for example, public interest would barely budge?

At the risk of oversimplifying, I suggest two interlocking reasons. First, people in China have unrealistic expectations that the government can do everything, and second, they believe that the media reports only that which the government approves. The result is that for every problem, the government is blamed, and no matter what the media says, people assume the truth is worse.

Recall the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) epidemic. When the government tried to hide the actual facts to avoid panic, the cover-up engendered wild rumours that were far worse than the actual facts. People believed the wild rumours, causing greater panic. Only when the truth was told did the public relax. It was a good lesson.

People in China have unrealistic expectations that the government can do everything

How to improve public trust? The party, I believe, has taken a decisive step by redefining the principal contradiction in society.

“Contradiction” is a Marxist term describing a kind of political analysis – “dialectical materialism” – which identifies “dynamic opposing forces” in society, and seeks to resolve tensions by applying “correct” political theories.

In Deng Xiaoping’s era, the principal contradiction was “the ever-growing material and cultural needs of the people versus backward social production” – a change most welcome from the prior contradiction of “proletariat versus bourgeoisie”, which catalysed severe, widespread and prolonged chaos and destruction during the political mass movements in the 1950s and 1960s, especially the ruinous Cultural Revolution.

Now, even as China achieves its goal of becoming a moderately prosperous society, fulfilling basic needs through economic growth, there is growing dissatisfaction with social conditions. Thus, in Xi’s “new era”, the principal contradiction is “between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life”.

As Xi said: “The needs to be met for the people to live a better life are increasingly broad. Not only have their material and cultural needs grown; their demand for democracy, rule of law, fairness and justice, security, and a better environment are increasing.”

This “new-era contradiction”, replacing quantitative gross domestic product growth with qualitative quality-of-life improvement, is what will now drive policy. For example, it is not that people cannot afford medical care, it’s that they must wait for hours at overcrowded hospitals and, even then, have only five minutes with a doctor. It’s not that people do not have good homes; it’s that they do not have clean air. Success will be measured more by the satisfaction of the people than by the growth rates of the economy.

Will “satisfaction” be harder to judge? Chinese people are not shy.

Implementing ways of thinking consistent with the new principal contradiction would mean trusting the people more. Here, the media plays a crucial role.

As with Sars, when truth about unpleasant events is censored, the cover-up engenders false rumours and fuels conspiracy theories. The media should be an ally, not an adversary, in the government’s quest for public trust.

The media should be an ally, not an adversary, in the government’s quest for public trust

This need not mean adapting the Western media model. China needs to find its own media model for its own stage of development – which should encourage, in cases like child abuse or tenement fires, truth to be told.

I can appreciate the opposite view. China’s leaders want the best for the Chinese people, of that I am sure, and there can be a perceived tension between, on the one hand, reporting bad news that could upset the public, and, on the other hand, restricting the reporting that could erode public trust. Given China’s social disparities and stage of development, such decisions are challenging.

When Xi first announced the new principal contradiction, some dismissed it as arcane party-speak. Public reaction to the child abuse and to the fire, albeit “minor” incidents among many, reveal its prescient and perspicacious wisdom.

Robert Lawrence Kuhn is a public intellectual, political/economics commentator, and an international corporate strategist. He is the host of Closer to China with R. L. Kuhn, a weekly show on CGTN, and the author of How China’s Leaders Think