Donald Trump has a point on steel tariffs, but does he have a solution?

Robert Delaney says there are real concerns about acquisitions of steel and aluminium for the US military as it gears up to confront authoritarian powers abroad – but Trump’s tariffs are a poor solution

US President Donald Trump has built an enthusiastic domestic following on a middle finger aimed at the rest of the world. So major trading partners hitting back at his plan for import tariffs on steel and aluminium probably don’t rattle him.

But when Trump comes under attack from right-leaning publications like The Wall Street Journal and business-friendly Bloomberg News, the White House should worry. The Journal’s editorial board called Trump’s plan “the biggest policy blunder of his presidency” and “one of the greatest displays of economic nonsense in presidential history”.

Using historical trade data showing an inverse relationship between the size of the US trade deficit and economic growth, Bloomberg columnist Noah Smith took apart the argument that restricting imports leads to stronger GDP growth.

“If imports compete with domestically produced goods, they could cause GDP to go down, but if they represent inputs into supply chains for domestic production, then cutting them off would hurt growth”, Smith said, noting that steel and aluminium are key inputs into many American-made goods.

Still, there’s a kernel of common sense in Trump’s drive to protect US steel and aluminium producers. The contention that unfair competition from state-subsidised foreign metal undercuts America’s military capability deserves examination.

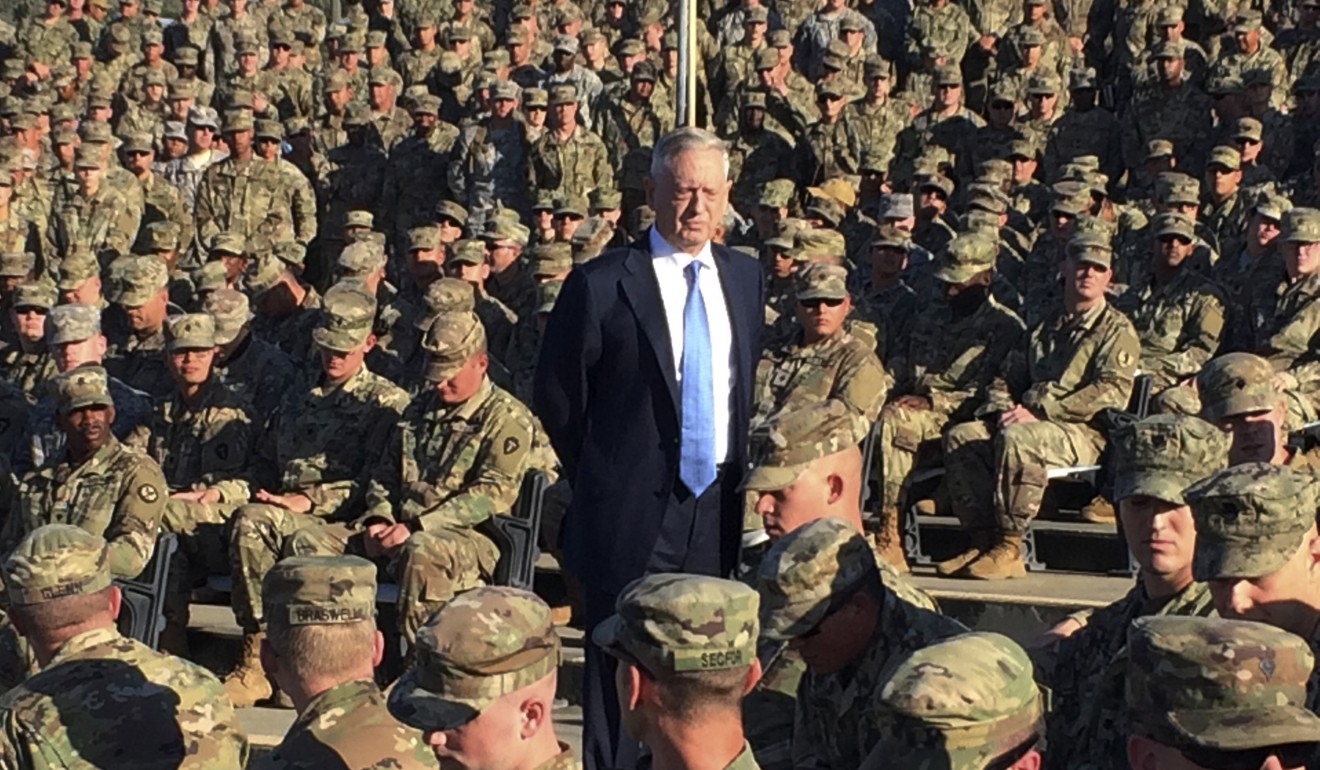

Firms making weaponry for the US armed forces require the highest grades of aluminium and steel. If reports that the United States is losing manufacturers of the metals needed to produce advanced military equipment to foreign competition are true, Washington should be expected to react, especially with the expansion of authoritarianism overseas and dire warnings from the US intelligence community that Russia launched a concerted campaign to influence the 2016 presidential election.

Developments in Asia, including North Korea’s willingness to lob missiles over Japan, and China’s construction of military bases in the South China Sea, should also give US defence officials a reason to want to ensure their supply chains are secure.

More than any other recent geopolitical development, China’s plan to scrap term limits for President Xi Jinping underscores how wrong were the “Washington consensus” optimists, who, in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin wall, assumed the rest would adopt liberal, democratic forms of government.

That hasn’t happened, so Washington can’t count on the world community to protect its interests. Unfortunately, the US will need upgraded military capabilities requiring the most advanced metals. But as with most of Trump’s initiatives – like wanting to arm teachers to counter school shootings – aluminium and steel tariffs represent a too-simplistic solution to a problem that requires more thinking.

US military procurement is already a works programme of sorts. Nearly 10 per cent of the country’s factory output – pegged at US$2.18 trillion in 2016 – is devoted to “production of weapons sold mainly to the Defence Department for use by the armed forces”, according to a recent New York Times report.

If buy-America regulations in military procurement aren’t enough to keep US producers of the required types of metal in business, the Department of Defence will need to work with suppliers to think of creative ways to guarantee domestic supply.

One way might be to shift some of the defence budget towards specific production lines at US metal producers, using a bidding process for the business. Creative minds should be able to find a solution centred on particular grades of metal instead of the entirety of the trade.

Of course, state-directed production is not an ideal solution, but is it any worse than Trump’s tariff wall?

Robert Delaney is a US correspondent for the Post based in New York