Globalisation of the People’s Bank of China puts pressure on Yi Gang as the world watches his every policy move

William Pesek says hopes that Yi Gang, the new People’s Bank of China governor, can introduce reforms slowly may be unrealistic as China’s economic policies take on greater importance globally

In one of his last press conferences as governor, Zhou Xiaochuan urged a “gradual” internationalisation of policies at the People’s Bank of China, a go-slow approach allowing space to open markets, reduce capital borders and curb risk.

His replacement may not enjoy that luxury as he confronts a world economy unwilling to wait.

Yi Gang inherits an institution that, ready or not, is being drawn into the fray of globalisation faster than Communist Party bigwigs might like. That’s partly a product of China’s scale – more than double the size of Japan’s economy and more than triple Germany’s. It also flows from President Xi Jinping’s ambitions to entrench China’s great power status.

The immediate PBOC challenges begin at home, of course. Chief among them is capping a debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratio soon to race beyond 300 per cent. That requires curtailing excesses among shadow banking shops, state-owned enterprises and local governments without derailing top-line growth. But Yi’s biggest headache may be dealing with the increased fallout his policy moves have in world markets.

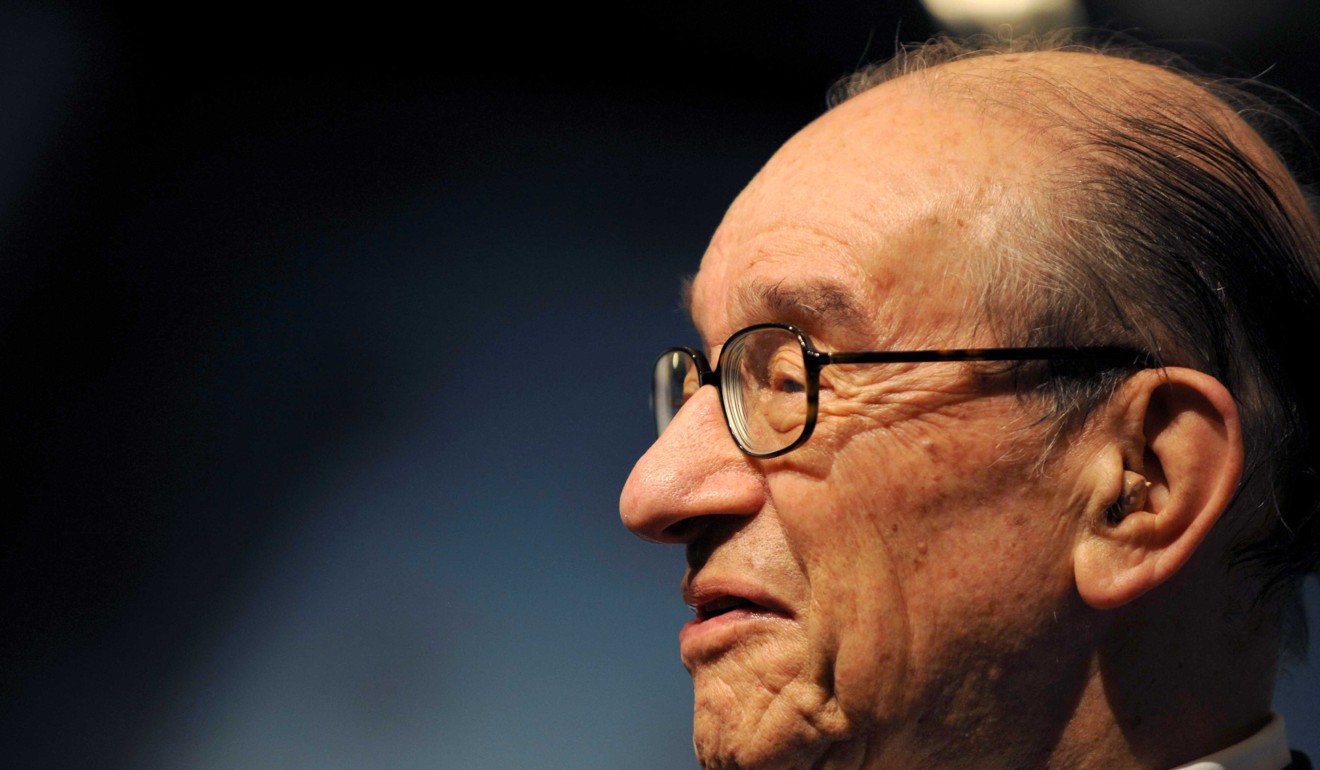

The globalisation of PBOC policies is really a product of Zhou’s success. As economic stories go, his nearly 16 years at the helm make for quite a volume. When Zhou took the reins in 2002, China’s central bank was but an obscure bureaucratic outpost. Alan Greenspan was in his heyday as Federal Reserve “maestro”, mainland markets were hermetically sealed and Beijing’s influence was a distant concept.

Zhou bequeaths Yi a US$12 trillion economy (versus US$1.5 trillion in 2002) growing at 6.5 per cent and the world’s largest store of foreign exchange reserves (US$3.1 trillion). On Zhou’s watch, China became the No. 1 trading nation, the biggest oil importer and generator of more than one-third of international growth. What stands out, too, are the PBOC’s deep ties with global peers, thanks largely to Zhou’s leadership – and longevity.

Along with straddling three Chinese presidents, Zhou’s tenure spanned four Fed chairs and three European Central Bank presidents, making him the longest-serving monetary leader among the Group of 20 nations. In that time, China scrapped its dollar peg, ended caps on deposit rates and won acceptance into the International Monetary Fund’s reserve-currency club.

Yes, Yi has rather big shoes to fill. As Zhou’s deputy for more than a decade, the US-trained Yi is a solid choice to keep China on the reform path and, as Zhou put it, “be bolder in opening up”. That would be easier, though, if not for the global forces closing in.

US President Donald Trump is his own great wall of threats. In the space of seven weeks, the US president ended the strong-dollar policy, slapped tariffs on steel (25 per cent) and aluminium (10 per cent) and is threatening more. So is a Fed, telegraphing four rate hikes this year. But the real pressure may come from investors hanging off the PBOC’s every word, deed and ambiguity.

The first hints of the PBOC’s growing footprint emerged in 2015, when the Fed was trying to pull off its first tightening in years. Turmoil in mainland markets forced the Fed to delay hitting the brakes. Fed watchers also buzzed that Beijing’s sales of US Treasury securities to stem capital outflows were doing the Fed’s tightening job for it.

Since then, any step in Beijing to tighten credit, tweak reserve requirements, recalibrate leverage rules or police shadow-banking activities has rocked world markets. The PBOC is already becoming the Fed of the East, surpassing the Bank of Japan. That’s forcing the PBOC to rethink not just how it implements policy, but how officials communicate.

Yi must end the PBOC’s penchant for issuing policy-shift statements at weekends, holidays (including Christmas, at times) and in the dead of night. The PBOC must also be more direct in what actions it is taking and the objectives it wants to achieve. That’s a tall task, considering its lack of independence. It’s an obligation of financial influence, though. As Beijing’s most visible global institution, its vital that Yi’s PBOC gets this right. Big missteps could roil markets and damage Beijing’s credibility.

In a sense, Yi finds himself where Greenspan did in 1987 when he took control of the Fed. Not an ideal comparison but, back then, the Fed’s policy moves were domestically focused and opacity was viewed as a strength. At the time, Fed watching was the West’s answer to Kremlinology. Hence the title of William Greider’s classic 1987 Fed book, Secrets of the Temple. Greenspan embarked on a kind of monetary glasnost. These days, one of the few growth areas for economists is for those skilled at divining secrets inside PBOC walls.

Yi also must create greater space for the PBOC to operate and wield its power. Zhou used his gravitas and status as a disciple of reform guru Zhu Rongji, premier from 1998 to 2003, to push three presidents to open the economy. Yi might have to make the opposite argument.

China is closing in on US GDP. By some estimates, it could top the US as soon as 2032. China’s capital markets, though, are minuscule relative to the United States and terribly inefficient. This paradox is symptomatic of the incongruities that fall to Yi to sort out.

Ready or not, the PBOC is morphing into the Fed of Asia. Yi must act quickly and craftily to ensure China’s most vital institution is ready for prime time. Moving gradually is no longer an option.

William Pesek is a Tokyo-based journalist and the author of Japanization: What the World Can Learn from Japan’s Lost Decades. Twitter: @williampesek