Trade war, inequality, populist revolt: baby boomers should reflect on their economic legacy this Easter

Andrew Sheng says that instead of decrying populism, the reaction against free trade and the rise of authoritarians, liberals in rich countries should examine how the globalisation process they supported led to a backlash

Easter weekend is a time for remembrance of life and death. Millions of Christians around the world remember the crucifixion and return of Jesus Christ for the salvation of all. Similarly, very soon it will be the Ching Ming festival, when the Chinese sweep the graves of their ancestors, not to worship them, but to be grateful for their sacrifices, without which there would be no present generation.

This week, I lost a friend, a soulmate with whom I could share ups and downs, and who could laugh at the world, be modest about his own contributions and who lived life to the fullest. His passing reminded me that the baby boomer generation to which we belong, born at or after the end of the second world war, is fading. The baby boomers created the greatest technological and business model breakthroughs in history, helping to create globalisation and, in the process, making billionaires richer than ever. Those who can afford it are living longer, healthier and richer than any generation in history, under the longest peacetime the world has enjoyed in centuries.

But this generation bequeaths to the next severe environmental deterioration and pollution, massive inequality and the largest debt overhang in history. One baby boomer has his finger on the nuclear trigger, threatening trade war and Armageddon against friend and foe alike.

And like the Rodgers and Hart song, billions today are “bewitched, bothered and bewildered” by what is going on.

The fortnight leading up to Easter has been remarkable for stunning events that dazzled even the most hardened political analysts. In Washington, US President Donald Trump fired his national security adviser and declared trade war, while Russian President Vladimir Putin got re-elected and China’s Two Sessions confirmed a new team under President Xi Jinping. The biggest surprise was North Korean leader Kim Jong-un showing up in Beijing, ahead of his planned meeting with Trump in May.

Will all this confusion end in tears?

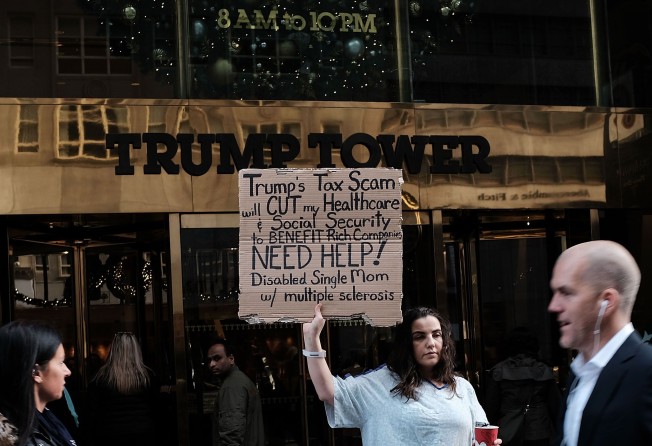

The current angst in the West is largely about the rise of populism, as the masses show their anger with the established order, lashing out at globalisation, foreigners, immigration, Islam, China, Russia and anyone that can be blamed. The liberals, including the mainstream media, are mesmerised by Trump, but forget that the more they attack him, the more powerful they make him in the eyes of his supporters. He is not in the business of change, but the business of optical change. Declaring a trade war satisfies his supporters. Whether it works or not is tomorrow’s concern.

The current sound and fury in global politics disguises the important signal: the elite have been attacking the wrong target. They should look in the mirror and ponder whether they are their own worst enemy.

True, Pax Americana with its liberal ideals created global peace, free trade and investment for 70 years. But despite the rhetoric of rules, human rights and free markets, the dark sides of financial capitalism – massive social inequality, crime, terrorism and failed US military interventions – can no longer be ignored.

The Bretton Woods narrative is broken. Its free market, auto-stabilising message cannot deal with the destabilising political, demographic and technological drivers of globalisation. We need a longer historical, philosophical and value-based narrative to deal realistically with these forces, as well as the primal anger over a system that only serves the elite few.

The reason is basic demography. With vast improvements in health care and technology, the global population exploded with the “green revolution” in the 1970s. The fall of communism brought a “labour shock”, adding several billion workers. The concurrent rise of the internet distributed information at speeds no one anticipated. Communications and WTO tariff reductions then truly created global trade, travel and investment. As the rich countries aged, they gained from “consumer surplus”, but worried about “labour deficit” – the job losses from immigration and technology.

The advanced countries papered over these issues with massive financialisation, printing money to fund growing debt at zero interest rates. In essence, the rest of the world financed the rich countries, and are now blamed for “unfair trade”.

The rich-nation liberals never saw the consequences of massive financialisation on the political divide. Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe puts it best: the elite refused to see what they don’t want to see. Because the elite could afford the best education, health care and treatment under the law, they completely ignored the true condition of the non-elite.

Populism therefore is the revenge of the non-elite, also known as the “Precariat” – the working class teetering precariously on the brink of sinking into poverty, homelessness and unemployment, despite working harder than ever.

Life is therefore a cycle of birth, growth, failure, age and then death. But there is always a new generation to inherit and deal with the failures of the current generation.

When we sit down and account for our successes and failures at Easter, the Ching Ming festival or any other period of peace and quiet, we have to bare our souls over our errors of omission or commission. Words are less important than deeds. And change, as another Nigerian academic put it, should be more than “motion in a barber’s chair: a lot of movement, but very little progress”.

Which is why I, as a member of the baby boomer generation, would ask for a lot of forgiveness and repentance for our sins.

Andrew Sheng reflects on global issues from an Asian perspective