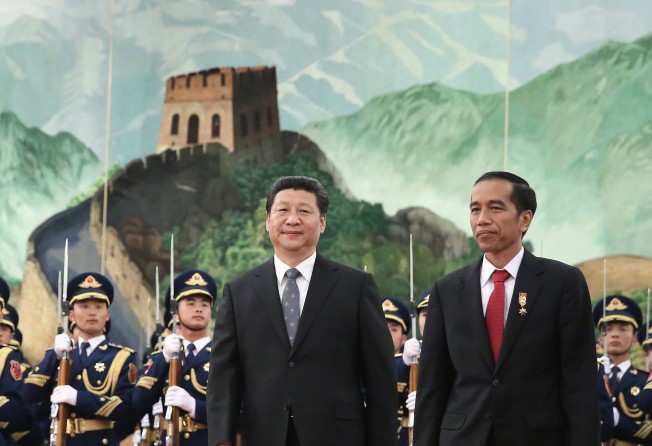

How Indonesia could be a bridge between China and the US in Asia

Luhut B. Pandjaitan says Indonesia and China have overcome their difficult past and share a belief in Asia’s development. However, as a middle power, Indonesia will not choose between China and the US, but could mediate between the two

As I prepare for a visit to China this week, it strikes me that countries often have to erase parts of history to create history. I have in mind how Indonesia and China have overcome a legacy of distrust to build a sustainable relationship in what is called the Asian Century. They have become natural partners in Asia.

In 1965, an insurrection by Indonesian communists aligned with Beijing led to one of the worst crises of contemporary Indonesian history. Relations with China plummeted; indeed, diplomatic ties ceased in 1967 and were only restored in 1990. Unfortunately, relations were tested again soon afterwards by attacks on ethnic Chinese in Jakarta in 1998 and by Beijing’s diplomatic intervention on their behalf, although the victims were Indonesian citizens.

The two decades since then have seen bilateral relations flourish to a degree that an uneasy past could not have foretold. China-Indonesia relations today are based not on the fortunes of any one community, but on a shared investment in a common Asian future at a time of acute transition. The United States remains the preponderant global power, but the scope and degree of its pre-eminence are changing. Unlike its expansive geopolitical past, when it laid the foundations of the global economic and strategic order after the end of the second world war, it has recently entered a mode of self-willed contraction.

There is no Chinese threat to Indonesia or to the world: all that Jakarta wishes to see is Beijing’s responsible strategic display of its economic and military power

US President Donald Trump has signalled the new conservative mood in American strategy by pulling his country out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris Accord on Climate Change. It would be wrong to say that America is becoming protectionist, let alone isolationist – it is not there as yet – but it would be right to see Trump as trying to shore up America’s domestic strengths so as to reposition it as a global power. In the interregnum, the degree of American influence abroad will decrease.

Following exactly the opposite trajectory, China is seeking to internationalise its domestic strengths. Having successfully focused on expanding its domestic economy to make it less dependent on the world, China has announced its re-entry on the global stage through a slew of measures that are simultaneously bold and pragmatic. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the “Belt and Road Initiative” focus on infrastructural connectivity, which is to the integrative demands of peacetime what blowing up roads and bridges is to the wartime need to deny terrain to an advancing enemy.

China is trying to integrate Asia, Europe and Africa on a scale unprecedented in recent human endeavour. It is a truly magnificent undertaking.

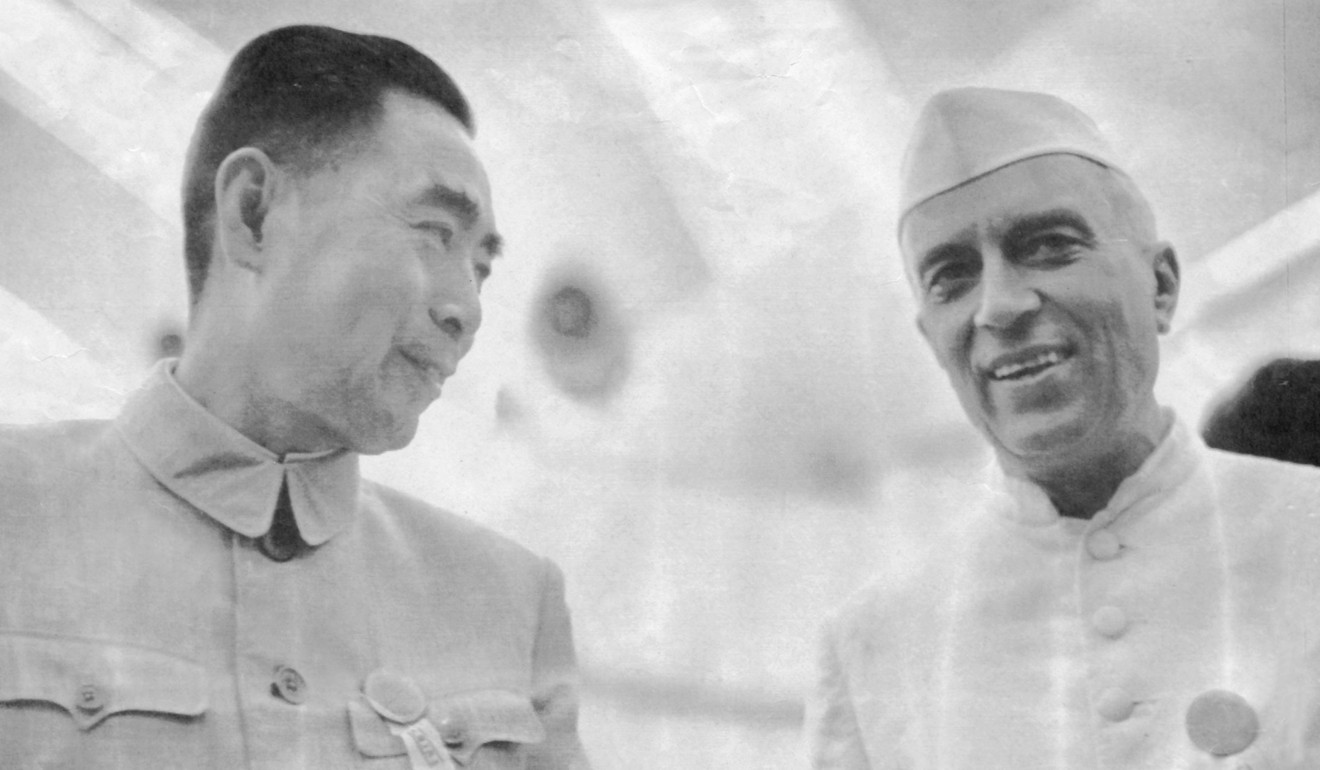

Indonesia, like China, is a viscerally Asianist country. Of course, both are globalists as well: witness the Bandung Conference of 1955 that sought to chart a future for the third world that would not be constrained by the binary polarities of the cold war. China, along with India and Egypt, was an important player at that signature gathering of Afro-Asian leaders on Indonesian soil.

Although the Non-Aligned Movement which emerged from the conference failed to achieve its global objectives, what Bandung set in motion was hope for a future where economic and intellectual commerce among nations would supersede reflexive recourse to war and subversion as a means to achieve national greatness.

That vision is taking concrete shape today in China’s leadership of the Afro-Asian sphere as the cold war recedes into memory.

Now, as then, Indonesia remains central to outcomes on the tri-continental expanse that China strives to bring within its strategic reach. How well China’s southern neighbours embrace its global project will help define its success. Indonesia, as Southeast Asia’s largest nation by virtue of geography, population and economy, will be instrumental in the success of Chinese efforts.

What distinguishes Indonesia is its nuanced relationship with China. Although many Indonesians privately, or even publicly, share the concerns of some of their Association of Southeast Asian Nation neighbours over China’s military assertiveness in the South China Sea, Indonesia’s foreign policy instincts preclude it from being a part of any global attempt to contain China. There is no Chinese threat to Indonesia or to the world: all that Jakarta wishes to see is Beijing’s responsible strategic display of its economic and military power.

Equally, however, Indonesia cannot be a part of any Chinese desire, if one exists, to form a cordon sanitaire against the American presence in the Indo-Pacific region. The US has legitimate interests here which tie in with the aspirations of Asian nations.

Indonesia is big enough to not be forced to take sides even among powerful nations. As an emergent Asian middle power, Indonesia must preserve its diplomatic freedom of action. Slipping into any exclusive sphere of influence, whether of the US or of China, would destroy the leverage that Indonesia possesses in its relations with both world powers. There is nothing special about Indonesia’s position. This is how middle powers much behave if they are to be middle powers.

The luxury of being situated in the middle of the shifting Asian balance of power gives Indonesia the advantage of being able to play an honest broker’s role in relations between China and the US. It is not a role that Jakarta covets but one which it would accept with grace were Beijing and Washington to deem it to be a credible intermediary.

Indonesia is a natural partner of China in an Asia that lies at the heart of America’s Indo-Pacific project.

Luhut B. Pandjaitan is Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs