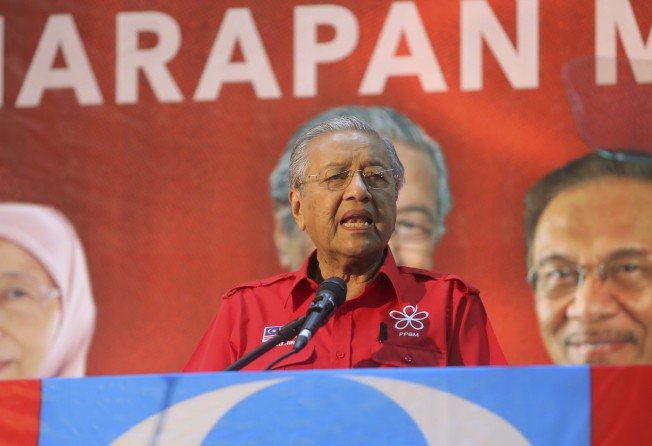

Can Mahathir redux undo his own legacy and build a corruption-free Malaysia?

Kevin Rafferty says questions remain after Mahathir Mohamed’s resounding victory at the polls. The biggest one is how different Malaysia’s new prime minister is from his younger self

Mahathir Mohamad returned in resounding triumph at the age of 92 to become the world’s oldest elected prime minister. It says a lot about the pernicious state of Malaysian politics that his slogan was his promise to clean up the corrupt government.

Prime Minister Najib Razak’s grand coalition government, Barisan Nasional, had all the advantages of 61 years of incumbency, backed by the resources of the state apparatus, including control of the media, choice of the election timing and a gerrymandered system. But Barisan Nasional won 79 of the 222 seats in the parliament, whereas Mahathir and his allies claimed 122 seats.

Nevertheless, questions remain about the future. Mahathir has announced that Anwar Ibrahim, his successor-turned-rival-turned-ally, will be pardoned by the country’s king. But will Mahathir yield to Anwar in two years, as promised?

Will Mahathir’s coalition be able to hold together? Will the 13-party Barisan Nasional splinter under the weight of no longer enjoying the spoils of power?

Will Mahathir yield to Anwar in two years, as promised?

Will Mahathir investigate the politicisation of justice that saw Anwar imprisoned twice? Will there be a fair investigation of the charges against Najib involving impropriety in the management of the 1Malaysia Development Bhd state investment fund?

Will Mahathir, who built his reputation as a champion of Malay special rights, be able to understand and convince colleagues that Malay predominance must be balanced by respect and rights for other races and other religions?

Is the Mahathir who became Malaysia’s seventh prime minister on Thursday, after railing against cronyism, corruption and kleptocracy, different from the Mahathir who, as the country’s fourth prime minister, opened the door to those very problems?

Will Mahathir realise that, however much he hates personal criticism, a free press and an independent judiciary are the best way to protect against corruption and excesses?

When I first went to Malaysia in the early 1970s, it seemed like paradise on earth, blessed with an abundance of food and commercial crops plus substantial minerals, including oil and gas, a bright population, a stable government and the rule of law. I cherished the dream that Malaysia could challenge Singapore for the aviation, commercial and financial leadership of Asia.

But signs of corruption were already visible. There were fierce rivalries within the superficially stable Barisan Nasional government while the Internal Security Act, an anti-terrorism law allowing for imprisonment without trial, was used against political opponents.

Malaysia’s delicate racial balance in the late 1970s – just over 50 per cent Malay and other ethnic groups classified as bumiputras (sons of the soil), 35 per cent Chinese and 11 per cent Indian – posed its own problems. Barisan Nasional started out as an alliance of the three major race-based parties – the United Malays National Organisation (Umno), the Malaysian Chinese Association and the Malaysian Indian Congress – in which all three shared the top jobs. However, later, Umno politicians began to dominate the key ministries.

Corporate restructuring of the colonial plantation and mining companies, including guaranteed shares for bumiputras, started before Mahathir became prime minister in 1981. But his plans to promote Malays and create a Malaysian industrial state offered Malays a chance to enrich themselves.

Initially, Mahathir and his deputy Musa Hitam seemed to be a dream team. But when the more popular Musa made a play for power after five years, he lost. Thereafter, the Barisan increasingly became a Mahathir vehicle. His ambitious industrial plans had mixed economic success, but created opportunities for supporters.

If Musa’s departure was politics as usual, Mahathir’s sacking of Anwar in 1998 was clearly a corrupt move. Anwar, originally a radical Islamic student leader, had a good reputation at home and abroad. Mahathir talked of a “father-son” relationship, while Anwar was appointed as chairman of the key International Monetary Fund committee.

But after Anwar complained of widespread cronyism and nepotism within Umno, Mahathir struck: he not only sacked him as minister, but hounded him into prison for corruption and sodomy in trials that Amnesty International said “exposed a pattern or political manipulation of key state institutions, including the police, the public prosecutor’s office and the judiciary”.

When Anwar’s conviction was set aside and he returned to politics, the retired Mahathir declared that he would “make a good prime minister of Israel”. This was such a studied insult that it makes the new Mahathir government, in which Anwar’s wife Wan Azizah Wan Ismail is deputy prime minister, looks shaky from the start.

The bottom line is that if Mahathir considers Najib’s government a kleptocracy, he has a lot of cleaning up to do.

For Malaysia, it is not quite paradise lost. Gross domestic product per capita is US$28,870 in purchasing power parity terms, 46th in the world according to the IMF. But tiny Singapore has moved far ahead, to US$90,5310 or fourth in the world. Equally important, Singapore comes sixth on Transparency International’s corruption index, whereas Malaysia has fallen to 62nd place.

Bright Chinese and Indians, seeing how the best opportunities go to Malays, have been leaving, so that today only 24.6 per cent of the 28 million Malaysians are Chinese, and only 7.3 per cent are Indians. The Malaysian dream has become tarnished by the worship of money. Can Mahathir change his personality and modus operandi to reform the country?

Kevin Rafferty was founder-editor of Business Times in Malaysia