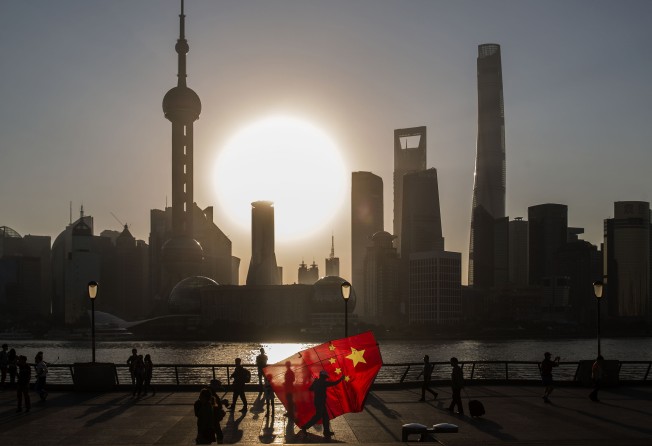

Why China’s economic success is no bellwether for foreign investors in Chinese stocks

- Alexander Treves says China’s stocks have often failed to generate the kind of returns for foreign investors its growth would suggest, but they should start to pay more attention to its increasingly attractive A-share market

China’s economic revolution has been one of the defining stories of the 21st century. Yet, for foreign investors in Chinese stocks, the returns have been far less impressive.

This is a stark reminder that equity investors buy companies, not economies. High economic growth may create an environment that is conducive to higher revenue growth, which in turn can contribute to increased earnings growth across the corporate sector – but this is not necessarily the case.

Much of the divergence between China’s economic and stock market returns can be explained by the composition of equity indices. Many of the first major Chinese companies which listed overseas, as represented by the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index, were state-owned enterprises whose primary focus was building domestic Chinese infrastructure. The other key listings were the state-owned banks, which now dominate the index.

Despite the more recent emergence of China’s internet giants, the MSCI China index remains quite narrow, with information technology businesses and financials comprising fully 60 per cent.

The onshore A-share index offers a wider choice beyond information technology and financials and has greater exposure to mid- and small-cap companies. It is also both broad and liquid, offering a wide range of equities for investors. Indeed, at the end of 2017, the A-share market contained more stocks with more than US$10 million in daily liquidity than all other emerging markets combined.

The A-share market is diversified by sector. The expanding middle class is both supporting and demanding an increasingly sophisticated set of consumer goods; for example, in beverages and fashion. The power of domestic brands is increasing. Chinese companies are moving up the technology curve from lower margin commoditised goods to higher-value areas such as handset components and software services. In some cases, China is pursuing its own business models; in payment systems, areas of gaming and financial technology, for example.

The A-share market also now trades at more attractive valuations than has been the case for much of its history.

There has been much commentary that MSCI inclusion will lead to inflows of foreign capital to the A-share market. However, while increasing accessibility for A-shares should be a positive for investor sentiment, the quality of those companies does not change with the indices that they are part of. The presence of a large, but still relatively inefficient, equity market is a more important factor for investors than index composition alone, particularly for global institutional investors who allocate holistically.

China’s government sees increased international involvement as one way of encouraging improved institutional structures in China’s investment industry, along with the deepening of its financial-sector reforms. Over time, this should help lengthen investment horizons and reduce market volatility as retail participation diminishes as a percentage of the whole.

However, no path is without its bumps. Corporate governance in China remains an area for scrutiny. Although misapplication of the stock suspension framework had been an issue in the past, the China Securities and Regulatory Commission has taken steps to tackle the use of suspensions and the disclosure around them.

An increase in the number of companies that pay dividends has been positive, but payout ratios certainly have room to grow. Transparency and capital allocation discipline remain uneven although they have improved over time. Macro headwinds for A-share equities include geopolitical friction such as trade concerns, and the challenges of multi-year efforts to rebalance the domestic economy.

Those challenges aside, China’s onshore equity market is increasingly comprised of companies that reflect powerful long-term domestic growth potential. Examples include structural winners in the consumer (such as the drinks market and growing domestic travel industry), health care and technology sectors. There are many alternatives to the commoditised low-margin export sectors, which are most vulnerable to tariffs.

Even as China’s economy rebalances and slows from previous breakneck rates, the opening up of the A-share market offers offshore investors the chance to choose higher-quality companies in structurally attractive areas.

China has the world’s second-largest stock market: whichever benchmarks international investors use, they will increasingly have to pay more attention to A-shares. The time to learn more is now.

Alexander Treves is an investment specialist in emerging markets and Asia-Pacific equities at J.P. Morgan Asset Management