Could China be the Middle East’s stabiliser-in-chief?

Arnab Neil Sengupta says as the Arab states seek to widen their circle of friends, China can enlarge its role in the Middle East if it views the region as more than an oil supplier and market for Chinese goods

Imagine there was an opening in the Middle East for a “stabiliser-in-chief” whose qualifications ran the gamut from impartial negotiator and deep-pocketed investor to generous aid-giver and geostrategic partner, nationality no bar.

Could China land the job, outbidding such rivals as the US, Canada, Russia, Turkey and France?

What could work in China’s favour is President Xi Jinping and his government’s approach to the Arab world, in all its complexity.

Does Beijing intend to treat the countries of the Middle East and North Africa as suppliers of oil and natural gas, buyers of Chinese goods and providers of lucrative business opportunities? Or will China engage with the Arab world just the way it is – a region with pockets of conflict alternating with oases of prosperity, but whose development potential lies largely untapped, waiting for a global power driven by something bigger than pure self-interest?

If history is any guide, choosing between the two approaches is not easy. But to use a favoured American phrase, this is a contest for Beijing to lose.

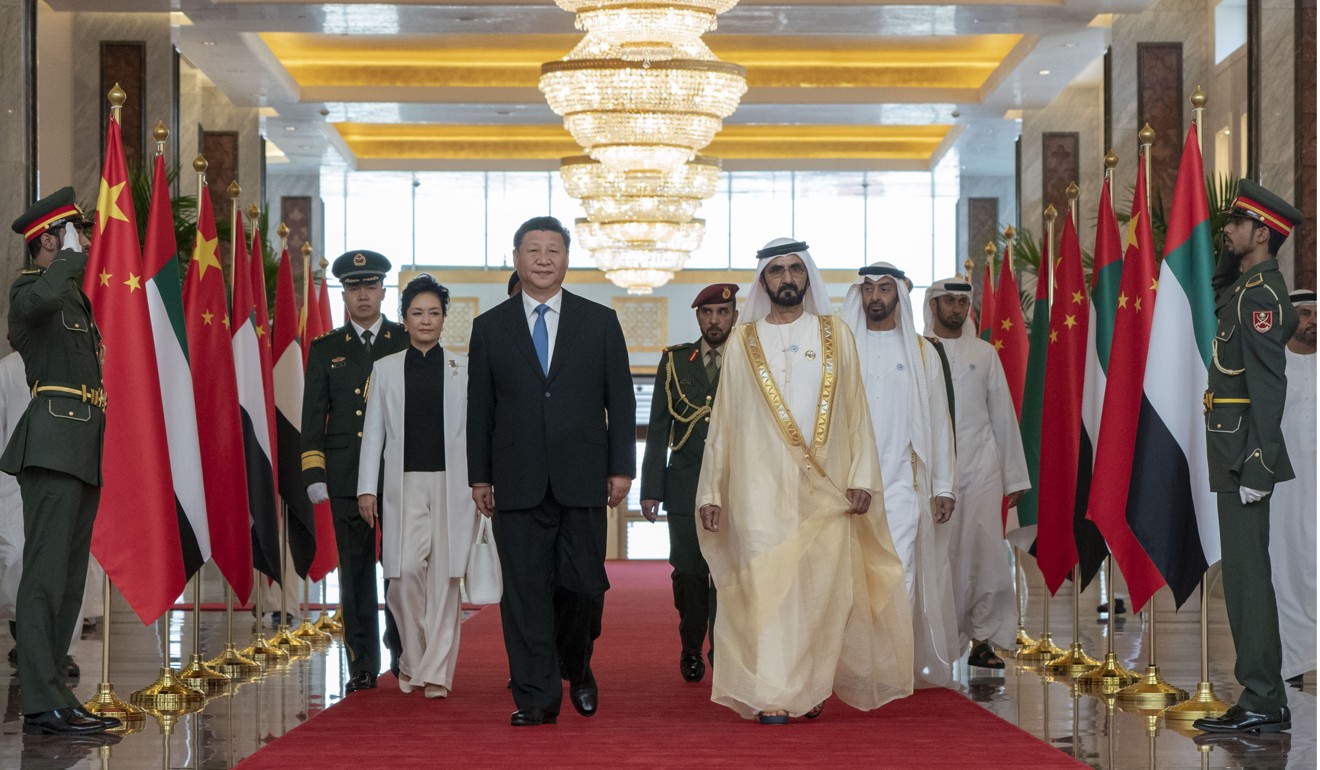

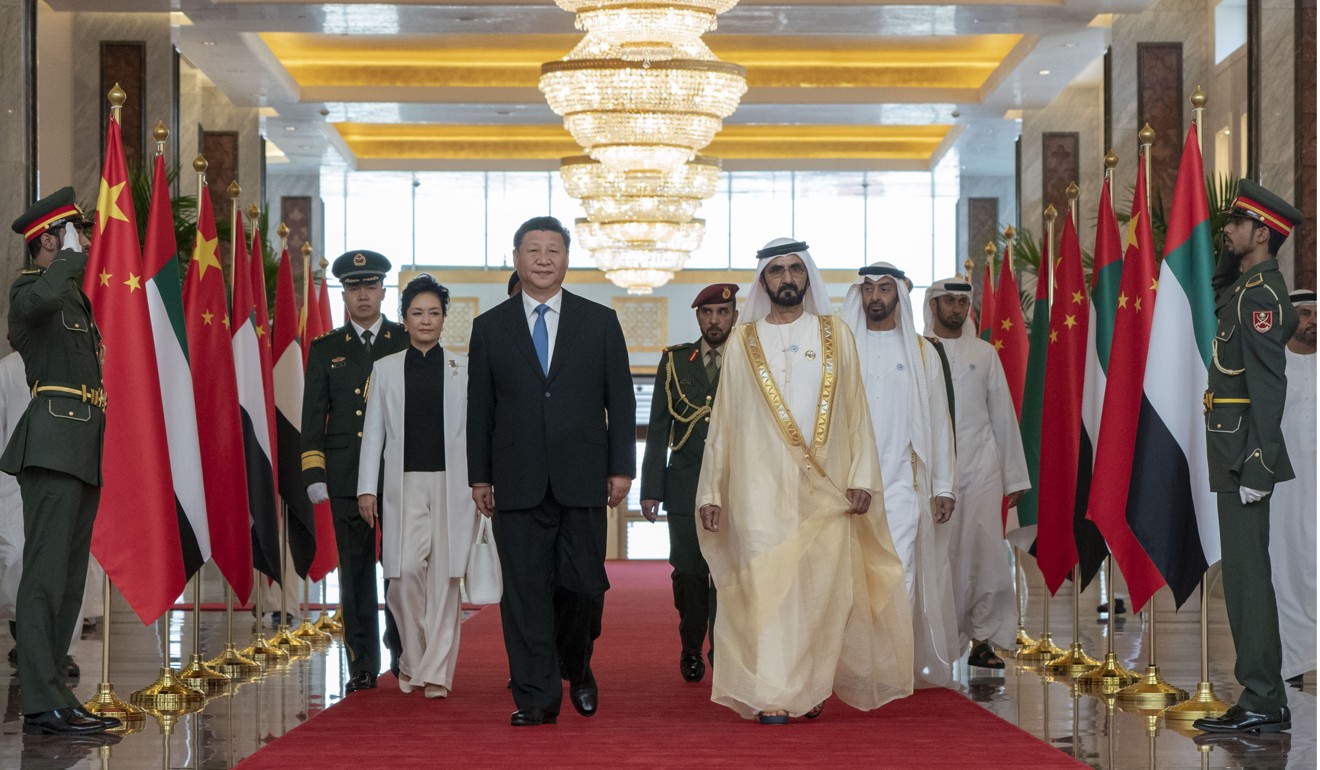

Take China’s relations with the United Arab Emirates, for instance. Judging by the news headlines, Xi’s recent visit to the country was all about trade and investment, with the red-carpet treatment he received and his signature Belt and Road Initiative occupying centre-stage.

But what the UAE really seeks is a multi-dimensional relationship. Together with Saudi Arabia, it wants to widen its circle of friends and economic partners, even as it seeks to reduce its dependence on the hydrocarbon sector for revenue and on Western military powers for security.

At the same time, the modernisers in charge of the UAE and Saudi Arabia appear keen to introduce China as well as other emerging powers to a tolerant and progressive aspect of Arab culture and values in the hope that it will help lay the foundation for solid partnerships.

As a strategy aimed at creating vast markets for China by building a business and infrastructure network connecting Asia with Europe and Africa, the Belt and Road Initiative does tantalise the Arab world with notions of a revival of the ancient Silk Road trade routes.

But oddly, for a number of reasons – both historical and practical – the economic philosophy and geopolitical vision of the Sunni monarchies continue to have much more in common with those of capitalist Western democracies than with the predilections of authoritarian states.

This doesn’t mean, though, that China stands little chance of becoming the Middle East’s most favoured world power any time soon. On the contrary, the facts suggest that the competition for this distinction is wide open.

First, several events since the beginning of the 2000s, ranging from George Bush’s invasion of Iraq to the Obama administration’s backing for the Arab Spring revolts, notably the Egyptian revolution, have convinced traditionally pro-Western Sunni states that past American behaviour is no guarantee of future trustworthiness.

The social and economic visions of the de facto rulers of Saudi Arabia and the UAE resonate with the global ambitions of Xi

As Zaki Nusseibeh, a UAE minister, said in an op-ed, “Naturally, countries such as the US and in Europe remain very important to us, but it is also a priority that we build stronger connections and cultural understanding in the major Asian countries, such as China and India.”

Second, the social and economic visions of the de facto rulers of Saudi Arabia and the UAE resonate with the global ambitions of Xi, exemplified by the launch of attention-grabbing undertakings.

Xi proposed in July, at a meeting in Beijing of the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum, a partnership covering not only the economy but also politics, culture, technology and strategic synergy.

Theoretically, Chinese and Arab interests and soft-power objectives should be in perfect harmony. In practice, however, the relationship is complicated.

Watch: Syrians rebuild historic city of Homs after years of war

Few issues highlight the political dissonance between the two sides like their views on the Syrian civil war, which has claimed nearly half a million lives and displaced more than 11 million people since 2011.

Voting records at the UN for the past seven years are an unambiguous study in contrasts: between China’s stout defence of President Bashar al-Assad in keeping with its pro-strongman foreign policy and Sunni countries’ rejection of his rule.

Then there is China’s alleged persecution of its 11-million-strong Uygur Muslim population in Xinjiang. Arab and Islamic countries have not spoken up about a report by UN experts of “arbitrary and mass detention of almost one million Uygurs” by Chinese authorities in “counter-extremism centres”.

It would be disingenuous, however, of China to conflate the official-level silence with Arab Muslims’ apathy towards its repeated crackdowns on Uygur Muslims.

On the bright side, the coming years could find China spoilt for choice in terms of incentives to distance itself slowly from Russia’s unpopular Middle East policies and align its strategic interests with those of its Arab economic partners.

Reports of PetroChina and Sinopec buying a stake in Saudi Aramco could just be the beginning.

A recalibration of its Syria policy, coupled with greater sensitivity in its treatment of its Muslim population, could easily elevate China’s moral authority in the Arab world

Indeed, with its already favourable public perceptions in many Middle East countries, as revealed by Pew Research Centre surveys, a recalibration of its Syria policy, coupled with greater sensitivity in its treatment of its Muslim population, could easily elevate China’s moral authority in the Arab world.

Beijing could burnish its reputation further by using its leverage as a major oil importer to rein in Iran and its regional proxies and to lend the services of its state-backed construction companies to enable the stabilisation of countries still reeling from the Arab Spring’s aftermath.

Finally, bearing in mind some of the damaging consequences of the Belt and Road Initiative, China could take steps now to ensure that poor Arab states taking part in the project do not slide deeper into indebtedness.

The Arab world will certainly calculate the returns on closer cooperation with China in economic and strategic terms. But for a region grappling with challenges, ranging from high population growth rates to technological backwardness, the long-term benefits of dialogue and interaction with China will probably be just as important.

Whether China has the appetite for the risks and rewards of the role of the Arab world’s stabiliser-in-chief remains to be seen.

Arnab Neil Sengupta is an independent journalist and commentator on the Middle East